Understanding Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD)

In the last blog, we introduced Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) as a computationally efficient optimization method. In this post, we’ll dive deeper into the mechanics of SGD, exploring its nuances, trade-offs, and how it compares to other gradient descent variants. Let’s unravel the details and gain a comprehensive understanding of these optimization techniques.

“Noisy” Gradient Descent

Instead of computing the exact gradient at every step, noisy gradient descent estimates the gradient using random subsamples. Surprisingly, this approximation often works well.

Why Does It Work?

Gradient descent is inherently iterative, meaning it has the chance to recover from previous missteps at each step. Leveraging noisy estimates can speed up the process without significantly impacting the final results.

Mini-batch Gradient Descent

The full gradient for a dataset \(D_n = (x_1, y_1), \dots, (x_n, y_n)\) is given by:

\[\nabla \hat{R}_n(w) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \nabla_w \ell(f_w(x_i), y_i)\]This requires the entire dataset, which can be computationally expensive. To mitigate this, we use a mini-batch of size \(N\), a random subset of the data:

\[\nabla \hat{R}_N(w) = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \nabla_w \ell(f_w(x_{m_i}), y_{m_i})\]Here, \((x_{m_1}, y_{m_1}), \dots, (x_{m_N}, y_{m_N})\) is the mini-batch.

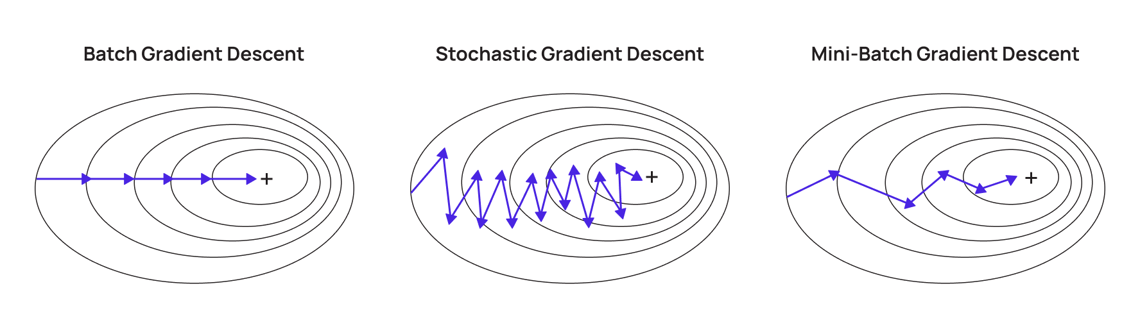

Batch vs. Stochastic Methods

Rule of Thumb:

- Stochastic methods perform well far from the optimum but struggle as we approach it.

- Batch methods excel near the optimum due to more precise gradient calculations.

Mini-batch Gradient Properties

- The mini-batch gradient is an unbiased estimator of the full gradient, meaning on average, the gradient computed using a minibatch (a small, random subset of the dataset) gives the same direction of descent as the gradient computed using the entire dataset.

-

This implies that while individual minibatch gradients may vary due to the randomness of the sample, their expected value matches the full batch gradient. This property allows Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) to make consistent progress toward the optimum without requiring computation over the entire dataset in each iteration.

-

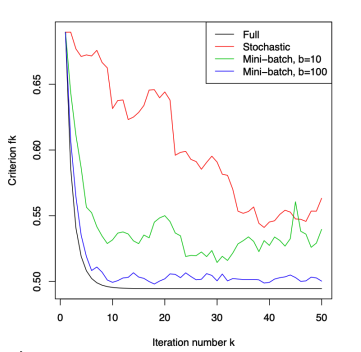

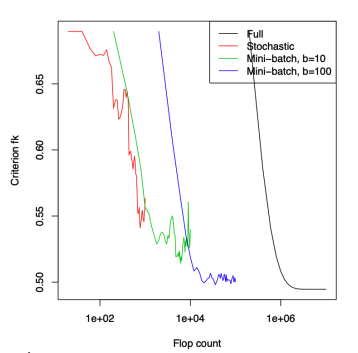

Larger mini-batches result in better estimates but are slower to compute:

- This is because averaging over more samples reduces randomness. Specifically, the variance is scaled by \(1/𝑁\), meaning larger minibatches produce more accurate and stable gradient estimates, closer to the full batch gradient.

Tradeoffs of minibatch size:

- Larger \(N\): Better gradient estimate, slower computation.

- Smaller \(N\): Faster computation, noisier gradient estimates.

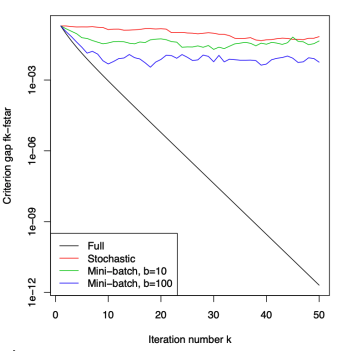

Convergence of SGD

To ensure convergence, diminishing step sizes like \(\eta_k = 1/k\) are often used. While gradient descent (GD) theoretically converges faster than SGD:

- GD is efficient near the minimum due to higher accuracy.

- SGD is more practical for large-scale problems where high accuracy is unnecessary.

In practice, SGD with fixed step sizes works well and can be adjusted using techniques like staircase decay or inverse time decay (\(1/t\)).

SGD Algorithm with Mini-batches

- Initialize \(w = 0\).

- Repeat:

- Randomly sample \(N\) points from \(D_n\): \({(x_i, y_i)}_{i=1}^N\).

- Update weights:

Why Diminishing Step Sizes? (Theoretical Aspects)

If \(f\) is \(L\)-smooth and convex, and the variance of \(\nabla f(x^{(k)})\) is bounded

\[\text{Var}(\nabla f(x^{(k)})) \leq \sigma^2\], then SGD with step size

\[\eta \leq \frac{1}{L}\]satisfies:

\[\min_k \mathbb{E}[\|\nabla f(x^{(k)})\|^2] \leq \frac{f(x^{(0)}) - f(x^*)}{\sum_k \eta_k} + \frac{L\sigma^2}{2} \frac{\sum_k \eta_k^2}{\sum_k \eta_k}\]Breaking it Down:

- L-Smooth and Convex Function:

- A function ( f ) is smooth if its gradient doesn’t change too rapidly. Specifically, an \(L\)-smooth function means that the gradient’s rate of change is bounded by a constant \(L\).

- A convex function means that it has a single global minimum, making optimization easier because we don’t have to worry about getting stuck in local minima.

- Variance of Gradient:

- The gradient at each step of SGD might not be exact. The variance \(\text{Var}(\nabla f(x^{(k)}))\) measures the “noise” or fluctuations in the gradient estimate. A smaller variance means the gradient is more stable.

What Does the Formula Mean?

The formula provides an upper bound on the expected squared magnitude of the gradient:

\[\min_k \mathbb{E}[\|\nabla f(x^{(k)})\|^2] \leq \frac{f(x^{(0)}) - f(x^*)}{\sum_k \eta_k} + \frac{L\sigma^2}{2} \frac{\sum_k \eta_k^2}{\sum_k \eta_k}\]-

Left Side: \(\min_k \mathbb{E}[\|\nabla f(x^{(k)})\|^2]\) represents the minimum expected squared gradient magnitude. A smaller value indicates that the gradient is approaching zero, meaning we’re getting closer to the optimal solution.

-

Right Side:

- The first term \(\frac{f(x^{(0)}) - f(x^*)}{\sum_k \eta_k}\) reflects how the gap between the initial point \(x^{(0)}\) and the optimal solution \(x^*\) decreases over time. The more steps we take (i.e., the larger the sum of the step sizes \(\eta_k\)), the smaller the gap becomes.

- The second term \(\frac{L\sigma^2}{2} \frac{\sum_k \eta_k^2}{\sum_k \eta_k}\) accounts for the variance in the gradient. If the step size doesn’t decrease over time, this variance term grows, which can destabilize the optimization process. The numerator \(\sum_k \eta_k^2\) grows faster than the denominator \(\sum_k \eta_k\), so increasing step sizes overall increases the second term. So, this term will dominate if the step size does not decrease.

Intuition Behind Diminishing Step Sizes:

-

Without diminishing step sizes - If you keep taking large steps, especially when close to the minimum, you risk overshooting the optimal solution. Large gradients or noisy estimates can lead to erratic behavior.

-

With diminishing step sizes - As we get closer to the minimum, reducing the step size helps take smaller, more controlled steps. This reduces the variance (noise) in the gradient and makes the convergence process smoother and more stable.

So, now why diminish step sizes?

Diminishing step sizes are important because:

- Early on, larger steps help explore the solution space and make significant progress.

- As you approach the optimal solution, smaller steps are needed to fine-tune the result and avoid overshooting. This balance helps the optimization process converge efficiently while maintaining stability.

More on the mathematical details of convergence will be covered in a separate blog post. For now, the key intuition to keep in mind is that diminishing step sizes help strike a balance between exploration (larger steps) and stability (smaller steps), leading to smoother convergence.

Summary

Gradient descent variants provide trade-offs in speed, accuracy, and computational cost:

- Full-batch gradient descent: Uses the entire dataset for gradient computation, yielding precise updates but high computational cost.

- Mini-batch gradient descent: Balances computational efficiency and gradient accuracy by using subsets of data.

- Stochastic gradient descent (SGD): Uses a single data point (\(N = 1\)) for updates, making it highly efficient but noisy.

When referring to SGD, always clarify the batch size to avoid ambiguity. Modern machine learning heavily relies on SGD due to its time and memory efficiency, especially for large-scale problems.

Example: Logistic Regression with \(\ell_2\)-Regularization

- Batch methods: Converge faster near the optimum.

- Stochastic methods: Are computationally efficient, especially for large datasets.

Understanding these trade-offs helps in choosing the right approach for different scenarios.

In the next blog, we’ll explore Gradient Descent Convergence Theorems and how to intuitively make sense out of it! See you.