Gradient Descent - A Detailed Walkthrough

In our last blog post, we discussed Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM). Let’s build on that foundation by exploring a concrete example: Linear Least Squares Regression. This will help us understand how gradient descent fits into the optimization landscape.

Linear Least Squares Regression

Problem Setup

We aim to minimize the empirical risk using linear regression. Here’s the setup:

- Loss function: \(\ell(\hat{y}, y) = (\hat{y} - y)^2\)

- Hypothesis space: \(\mathcal{F} = \{ f : \mathbb{R}^d \to \mathbb{R} \mid f(x) = w^\top x, \, w \in \mathbb{R}^d \}\)

- Data set: \(\mathcal{D}_n = \{(x_1, y_1), \dots, (x_n, y_n)\}\) Our goal is to find the ERM solution: \(\hat{f} \in \mathcal{F}\). Objective Function

We want to find the function in \(\mathcal{F}\), parametrized by \(w \in \mathbb{R}^d\), that minimizes the empirical risk:

\[\hat{R}_n(w) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n (w^\top x_i - y_i)^2\]This leads to the optimization problem: \(\min_{w \in \mathbb{R}^d} \hat{R}_n(w)\)

Although ordinary least squares (OLS) offers a closed-form solution (refer to the provided resource to understand OLS), gradient descent proves more versatile, particularly when closed-form solutions are not feasible.

Gradient Descent

Gradient descent is a powerful optimization technique for unconstrained problems.

Unconstrained Optimization Setting

We assume the objective function \(f : \mathbb{R}^d \to \mathbb{R}\) is differentiable, and we aim to find:

\[x^* = \arg \min_{x \in \mathbb{R}^d} f(x)\]The Gradient

The gradient is a fundamental concept in optimization. For a differentiable function \(f : \mathbb{R}^d \to \mathbb{R}\), the gradient at a point \(x_0 \in \mathbb{R}^d\) is denoted by \(\nabla f(x_0)\). It represents the vector of partial derivatives of \(f\) with respect to each dimension of \(x\):

\[\nabla f(x_0) = \left[ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1}(x_0), \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_2}(x_0), \dots, \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_d}(x_0) \right]\]Key points:

- The gradient points in the direction of the steepest increase of the function \(f(x)\) starting from \(x_0\).

- The magnitude of the gradient indicates how steep the slope is in that direction.

For example, consider a 2D function \(f(x, y)\). The gradient at a point \((x_0, y_0)\) is:

\[\nabla f(x_0, y_0) = \left[ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0, y_0), \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(x_0, y_0) \right]\]This tells us how \(f\) changes with respect to \(x\) and \(y\) near \((x_0, y_0)\).

Importance in Optimization

The gradient is crucial because it provides the direction in which the function \(f(x)\) increases most rapidly. To minimize \(f(x)\):

- We move in the opposite direction of the gradient, as this is where the function decreases most rapidly.

Geometric Interpretation

Imagine a 3D surface representing a function \(f(x, y)\). At any point on the surface:

- The gradient vector points uphill, perpendicular to the contour lines (or level curves) of the function.

- To find a minimum, we “descend” by moving in the opposite direction of the gradient vector.

This understanding lays the foundation for applying gradient descent effectively in optimization problems.

Gradient Descent Algorithm

To iteratively minimize \(f(x)\), follow these steps:

- Initialize: \(x \leftarrow 0\)

- Repeat: \(x \leftarrow x - \eta \nabla f(x)\)

- until a stopping criterion is met.

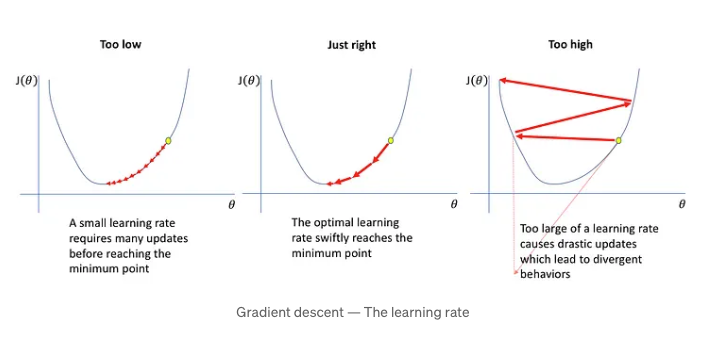

Here, \(\eta\) is the step size (or learning rate). Choosing \(\eta\) appropriately is critical to avoid divergence or slow convergence. “Step size” is also referred to as “learning rate” in neural networks literature.

Path of a Gradient Descent Algorithm

Insights into Gradient Descent

Step Size

- Fixed step size: Works if small enough.

- If \(\eta\) is too large, the process might diverge.

- Experimenting with multiple step sizes is often necessary.

- Big vs. Small Steps:

- Big steps: In flat regions where the gradient is small, larger steps accelerate convergence.

- Small steps: In steep regions where the gradient is large, smaller steps ensure stability and prevent overshooting.

- Adaptive methods like Adam or RMSprop leverage this intuition by dynamically adjusting the step size based on the gradient’s magnitude or past behavior.

Convergence

Gradient descent converges to a stationary point (where the derivative is zero) for differentiable functions. These stationary points could be:

- Local minima

- Local maxima

- Saddle points

For convex functions(Added Reference), gradient descent can converge to the global minimum.

The following theorems are often overlooked when learning about gradient descent. We’ll dive into them in detail in a separate blog, but for now, give them a quick read and continue.

Theorem: Convergence of Gradient Descent with Fixed Step Size

Suppose \(f : \mathbb{R}^d \to \mathbb{R}\) is convex and differentiable, and \(\nabla f\) is Lipschitz continuous with constant \(L > 0\) (i.e., \(f\) is L-smooth). This means:

\[\|\nabla f(x) - \nabla f(x')\| \leq L \|x - x'\|\]for any \(x, x' \in \mathbb{R}^d\).

Result:

If gradient descent uses a fixed step size \(\eta \leq \frac{1}{L}\), then:

\[f(x^{(k)}) - f(x^*) \leq \frac{\|x^{(0)} - x^*\|^2}{2\eta k}\]Implications:

- Gradient descent is guaranteed to converge under these conditions.

- The convergence rate is \(O(1/k)\)

Strongly Convex Functions

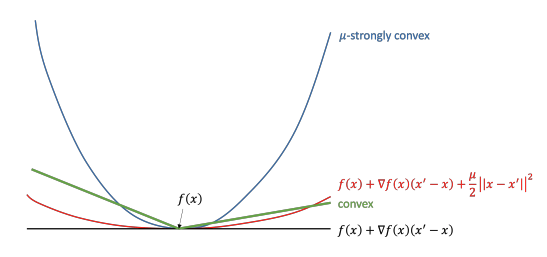

A function \(f\) is \(\mu\)-strongly convex if:

\[f(x') \geq f(x) + \nabla f(x) \cdot (x' - x) + \frac{\mu}{2} \|x - x'\|^2\]

Convergence Theorem for Strongly Convex Functions

If \(f\) is both \(L\)-smooth and \(\mu\)-strongly convex, with step size \(0 < \eta \leq \frac{1}{L}\), then gradient descent achieves convergence with the following inequality:

\[\|x^{(k)} - x^*\|^2 \leq (1 - \eta \mu)^k \|x^{(0)} - x^*\|^2\]This implies linear convergence, but it depends on \(\mu\). If the estimate of µ is bad then the rate is not great.

Stopping Criterion

- Stop when \(\|\nabla f(x)\|_2 \leq \epsilon\), where \(\epsilon\) is a small threshold(of our choice). Why? At a local minimum, \(\nabla f(x) = 0\). If the gradient becomes small and plateaus, further updates are unlikely to significantly reduce the objective function, so we can stop the gradient updates.

- Early Stopping

- Evaluate the loss on validation data (unseen held-out data) after each iteration.

- Stop when the loss no longer improves or starts to worsen.

Quick recap: Gradient Descent for ERM

Given a hypothesis space \(F = \{f_w : X \to Y \mid w \in \mathbb{R}^d\}\), we aim to minimize:

\[\hat{R}_n(w) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \ell(f_w(x_i), y_i)\]Gradient descent is applicable if \(\ell(f_w(x_i), y_i)\) is differentiable with respect to \(w\).

Scalability

At each iteration, we compute the gradient at the current \(w\) as:

\[\nabla \hat{R}_n(w) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \nabla_w \ell(f_w(x_i), y_i)\]This requires \(O(n)\) computation per step, as we have to iterate over all n training points to take a single step. To scale better, alternative methods like stochastic gradient descent (SGD) can be considered.

Gradient descent is an indispensable tool for optimization, especially in machine learning. By understanding its principles, convergence properties, and practical considerations, we can effectively tackle a variety of optimization problems.

Stay tuned for the next post, where we’ll explore stochastic gradient descent and its variations for scalability!

References & Good Resources for Visualizing Gradient Descent:

- 3D Gradient Descent

- Animating Gradient Descent

- A Visual Explanation of Gradient Descent Methods (Momentum, AdaGrad, RMSProp, Adam) – Towards Data Science (Variations of Gradient Descent)

- Yennhi95zz, 2023. #4. A Beginner’s Guide to Gradient Descent in Machine Learning. Medium

- Path of a Gradient Descent Algorithm (Image Credit)