Bayesian Machine Learning - Mathematical Foundations

When working with machine learning models, it’s crucial to understand the underlying statistical principles that drive our methods. Whether you’re a frequentist or a Bayesian, the starting point often involves a parametric family of densities. This concept forms the foundation for inference and is used to model the data we observe.

Parametric Family of Densities

A parametric family of densities is defined as a set

\[\{p(y \mid \theta) : \theta \in \Theta\},\]where \(p(y \mid \theta)\) is a density function over some sample space \(Y\), and \(\theta\) represents a parameter in a finite-dimensional parameter space \(\Theta\).

In simpler terms, this is a collection of probability distributions, each associated with a specific value of the parameter \(\theta\). When we refer to “density,” it’s worth noting that this can be replaced with “mass function” if we’re dealing with discrete random variables. Similarly, integrals can be replaced with summations in such cases.

This framework is the common starting point for both classical statistics and Bayesian statistics, as it provides a structured way to think about modeling the data.

Frequentist or “Classical” Statistics

In frequentist statistics, we also work with the parametric family of densities \(\{p(y \mid \theta) : \theta \in \Theta\}\), assuming that the true distribution \(p(y \mid \theta)\) governs the world we observe. This means there exists some unknown parameter \(\theta \in \Theta\) that determines the true nature of the data.

If we had direct access to this true parameter \(\theta\), we wouldn’t need statistics at all! However, in practice, we only have a dataset, denoted as

\[D = \{y_1, y_2, \dots, y_n\},\]where each \(y_i\) is sampled independently from the true distribution \(p(y \mid \theta)\).

This brings us to the heart of statistics: how do we make inferences about the unknown parameter \(\theta\) using only the observed data \(D\)?

Point Estimation

One fundamental problem in statistics is point estimation, where the goal is to estimate the true value of the parameter \(\theta\) as accurately as possible.

To do this, we use a statistic, denoted as \(s = s(D)\), which is simply a function of the observed data. When this statistic is designed to estimate \(\theta\), we call it a point estimator, represented as \(\hat{\theta} = \hat{\theta}(D)\).

A good point estimator is one that is both:

- Consistent: As the sample size \(n\) grows larger, the estimator \(\hat{\theta}_n\) converges to the true parameter \(\theta\).

- Efficient: The estimator \(\hat{\theta}_n\) extracts the maximum amount of information about \(\theta\) from the data, achieving the best possible accuracy for a given sample size.

One of the most popular methods for point estimation is the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE). While we’ve already covered it, let’s revisit it through a concrete example to reinforce our understanding.

Example: Coin Flipping and Maximum Likelihood Estimation

Let’s consider the simple yet illustrative problem of estimating the probability of a coin landing on heads.

Here, the parametric family of mass functions is given by:

\[p(\text{Heads} \mid \theta) = \theta, \quad \text{where } \theta \in \Theta = (0, 1).\]The parameter \(\theta\) represents the probability of the coin landing on heads. Our goal is to estimate this parameter based on observed data.

If this seems a bit confusing, seeing \(\theta\) in two places, let’s clarify it first.

Imagine you have a coin, and you’re curious about how “fair” it is. A perfectly fair coin has a 50% chance of landing heads or tails, but your coin might be biased. To capture this bias mathematically, you introduce a parameter, \(\theta\), which represents the probability of the coin landing on heads.

We write this as:

\[p(\text{Heads} \mid \theta) = \theta\]Let’s break this down with intuition:

- What does \(\theta\) mean?

\(\theta\) is the coin’s “personality.” For example:- If \(\theta = 0.8\), it means the coin “loves” heads, and there’s an 80% chance it will land heads on any given flip.

- If \(\theta = 0.3\), the coin is biased toward tails, and there’s only a 30% chance of heads.

-

What does \(p(\text{Heads} \mid \theta) = \theta\) mean?

This equation ties the probability of getting heads to the parameter \(\theta\). It’s like saying: “The parameter \(\theta\) is the probability of heads.” For every coin flip, \(\theta\) directly determines the likelihood of heads. - Why is this useful?

It simplifies modeling. Instead of treating each flip as random and unconnected, we assume there’s a fixed bias, \(\theta\), that governs the coin’s behavior. Once we observe enough flips (data), we can estimate \(\theta\) and predict future outcomes.

A relatable example might be…

Imagine a factory making coins with varying biases. Each coin is labeled with its bias, \(\theta\), ranging between 0 (always tails) and 1 (always heads). If you’re handed a coin without a label, your job is to figure out its bias by flipping it multiple times and observing the outcomes.

This is the setup for the equation \(p(\text{Heads} \mid \theta) = \theta\). It tells us the coin’s behavior is entirely controlled by its bias, \(\theta\), and allows us to estimate it from observed data. Data and Likelihood Function

I hope that clears things up, and we’re good to proceed!

Suppose we observe the outcomes of \(n\) independent coin flips, represented as:

\[D = (\text{H, H, T, T, T, T, T, H, ... , T}),\]where \(n_h\) is the number of heads, and \(n_t\) is the number of tails. Since each flip is independent, the likelihood function for the observed data is:

\[L_D(\theta) = p(D \mid \theta) = \theta^{n_h} (1 - \theta)^{n_t}.\]Log-Likelihood and Optimization

Rather than working directly with the likelihood function, which involves products and can become cumbersome, we typically maximize the log-likelihood function for computational simplicity. The log-likelihood is:

\[\log L_D(\theta) = n_h \log \theta + n_t \log (1 - \theta).\]The maximum likelihood estimate (MLE) of \(\theta\) is the value that maximizes this log-likelihood:

\[\hat{\theta}_{\text{MLE}} = \underset{\theta \in \Theta}{\text{argmax}} \, \log L_D(\theta).\]Derivation of the MLE

To find the MLE, we compute the derivative of the log-likelihood with respect to \(\theta\), set it to zero, and solve for \(\theta\):

\[\frac{\partial}{\partial \theta} \big[ n_h \log \theta + n_t \log (1 - \theta) \big] = \frac{n_h}{\theta} - \frac{n_t}{1 - \theta}.\]Setting this derivative to zero:

\[\frac{n_h}{\theta} = \frac{n_t}{1 - \theta}.\]Simplifying this equation gives:

\[\theta = \frac{n_h}{n_h + n_t}.\]Thus, the MLE for \(\theta\) is:

\[\hat{\theta}_{\text{MLE}} = \frac{n_h}{n_h + n_t}.\]Intuition Behind the MLE

The result makes intuitive sense: the MLE simply calculates the proportion of heads observed in the data. It uses the empirical frequency as the best estimate of the true probability of heads, given the observed outcomes.

While frequentist approaches like MLE provide a single “best” estimate for \(\theta\), Bayesian methods take a different perspective. Instead of finding a point estimate, Bayesian inference quantifies uncertainty about \(\theta\) using probability distributions. This leads to the concepts of prior distributions and posterior inference, which is what we’re going to explore next.

Bayesian Statistics: An Introduction

In the frequentist framework, the goal is to estimate the true parameter \(\theta\) using the observed data. However, Bayesian statistics takes a fundamentally different approach by introducing an important concept: the prior distribution. This addition allows us to explicitly incorporate prior beliefs about the parameter into our analysis and update them rationally as we observe new data.

The Prior Distribution: Reflecting Prior Beliefs

A prior distribution, denoted as \(p(\theta)\), is a probability distribution over the parameter space \(\Theta\). It represents our belief about the value of \(\theta\) before observing any data. For instance, if we believe that \(\theta\) is more likely to lie in a specific range, we can encode this belief directly into the prior.

A Bayesian Model: Combining Prior and Data

A [parametric] Bayesian model is constructed from two key components:

- A parametric family of densities \(\{p(D \mid \theta) : \theta \in \Theta\}\) that models the likelihood of the observed data \(D\) given \(\theta\).

- A prior distribution \(p(\theta)\) on the parameter space \(\Theta\).

These two components combine to form a joint density over \(\theta\) and \(D\):

\[p(D, \theta) = p(D \mid \theta) p(\theta).\]This joint density encapsulates both the likelihood of the data and our prior beliefs about the parameter.

Posterior Distribution: Updating Beliefs

The real power of Bayesian statistics lies in the ability to update prior beliefs after observing data. This is achieved through the posterior distribution, denoted as \(p(\theta \mid D)\).

- The prior distribution \(p(\theta)\) captures our initial beliefs about \(\theta\).

- The posterior distribution \(p(\theta \mid D)\) reflects our updated beliefs after observing the data \(D\).

By applying Bayes’ rule, we can express the posterior distribution as:

\[p(\theta \mid D) = \frac{p(D \mid \theta) p(\theta)}{p(D)},\]where:

- \(p(D \mid \theta)\) is the likelihood, capturing how well \(\theta\) explains the observed data.

- \(p(\theta)\) is the prior, encoding our initial beliefs about \(\theta\).

- \(p(D)\) is a normalizing constant, ensuring the posterior integrates to 1.

Simplifying the Posterior

When analyzing the posterior distribution, we often focus on terms that depend on \(\theta\). Dropping constant factors that are independent of \(\theta\), we write:

\[p(\theta \mid D) \propto p(D \mid \theta) \cdot p(\theta),\]where \(\propto\) denotes proportionality.

In practice, this allows us to analyze and work with the posterior distribution more efficiently. For instance, the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimate of \(\theta\) is given by:

\[\hat{\theta}_{\text{MAP}} = \underset{\theta \in \Theta}{\text{argmax}} \, p(\theta \mid D).\]A Way to Think About It:

A helpful way to think of Bayesian methods is to imagine you’re trying to predict the outcome of an event, but you have some prior knowledge (or beliefs) about it. For example, let’s say you’re predicting whether a student will pass an exam, and you have prior knowledge that most students in the class have been doing well. This prior belief can be represented as a probability distribution, which reflects how confident you are about the parameter (like the likelihood of passing).

As you collect more data (say, the student’s past performance or study hours), Bayesian methods update your belief (the prior) to form a new, updated belief, called the posterior distribution. The more data you have, the more confident the posterior becomes about the true outcome.

So, in essence:

- Prior distribution = What you believe before observing data (your initial guess).

- Likelihood = How the observed data might be related to your belief.

- Posterior distribution = Your updated belief after observing the data.

In Bayesian inference, the goal is to calculate the posterior, which balances the prior belief with the observed data.

Example: Bayesian Coin Flipping

Let’s revisit the coin-flipping example, but this time from a Bayesian perspective. We start with the parametric family of mass functions:

\[p(\text{Heads} \mid \theta) = \theta, \quad \text{where } \theta \in \Theta = (0, 1).\]To complete our Bayesian model, we also need to specify a prior distribution over \(\theta\). One common choice is the Beta distribution, which is particularly convenient for this problem.

Beta Prior Distribution

The Beta distribution, denoted as \(\text{Beta}(\alpha, \beta)\), is a flexible family of distributions defined on the interval \((0, 1)\). Its density function is:

\[p(\theta) \propto \theta^{\alpha - 1} (1 - \theta)^{\beta - 1}.\]

For our coin-flipping example, we can use:

\[p(\theta) \propto \theta^{h - 1} (1 - \theta)^{t - 1},\]where \(h\) and \(t\) represent our prior “counts” of heads and tails, respectively.

The mean of the Beta distribution is:

\[\mathbb{E}[\theta] = \frac{h}{h + t},\]and its mode (for \(h, t > 1\)) is:

\[\text{Mode} = \frac{h - 1}{h + t - 2}.\]A Way to Think of This Distribution:

Imagine you’re trying to estimate the probability of rain on a given day in a city you’ve never visited. You don’t have any direct weather data yet, but you do have some general knowledge about the region. Based on this, you form an initial belief about how likely it is to rain—maybe you’re unsure, so you assume it’s equally likely to rain or not, or maybe you’ve heard that it’s usually dry there.

- The Beta distribution helps you represent this uncertainty. It’s like a flexible tool that encodes your prior beliefs about the probability of rain, and you can adjust these beliefs based on what you know or expect.

- If you’re totally uncertain, you might use a uniform prior (where \(\alpha = \beta = 1\)), meaning you’re equally unsure whether rain is more likely or not.

- If you’ve already heard that it tends to rain more often, say 70% of the time, you could choose \(\alpha = 7\) and \(\beta = 3\) to reflect this prior information.

As you gather more data—say, after several days of weather observations—you can update your beliefs about the likelihood of rain. Each new observation (rain or no rain) “shapes” your distribution.

-

The mean \(\mathbb{E}[\theta] = \frac{h}{h + t}\) represents the average likelihood of rain after considering all your prior knowledge and the observed days. This is your updated best guess about how likely it is to rain on any given day.

-

The mode \(\text{Mode} = \frac{h - 1}{h + t - 2}\), which reflects the most probable value of \(\theta\) after observing data, might give you a better estimate if the weather has shown a clear tendency over time (e.g., if it’s rained most days).

In essence, the Beta distribution allows you to start with an initial belief (or no belief) about the probability of rain, and as you observe more data, you continuously refine that belief. This is what makes Bayesian inference powerful—it enables you to update your beliefs rationally based on new evidence.

Why Use the Beta Prior Distribution in this Coin Flipping Problem?

The Beta distribution is particularly well-suited for modeling probabilities in Bayesian statistics, especially in problems like coin flipping. Here are a few reasons why it’s a good choice:

-

Support on (0, 1): The Beta distribution is defined over the interval \(\theta \in (0, 1)\), which matches the range of possible values for \(\theta\) in the coin-flipping example. Since \(\theta\) represents the probability of getting heads, it must lie between 0 and 1.

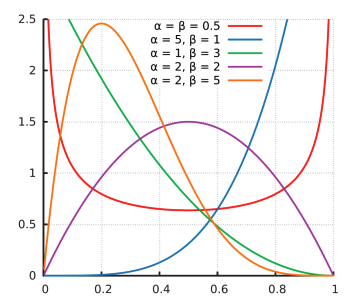

- Flexibility: The Beta distribution is very flexible in shaping its probability density. By adjusting the parameters \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), we can model a wide variety of prior beliefs about \(\theta\):

- When \(\alpha = \beta = 1\), the Beta distribution is uniform, indicating that we have no strong prior belief about whether heads or tails is more likely.

- When \(\alpha > \beta\), the distribution is biased towards heads, and when \(\alpha < \beta\), it is biased towards tails.

- The parameters can also reflect observed data: if you’ve already seen \(h\) heads and \(t\) tails, the Beta distribution can be chosen with \(\alpha = h + 1\) and \(\beta = t + 1\), which matches the idea of “updating” your beliefs based on the data you observe.

- Intuitive Interpretation: The Beta distribution is easy to interpret in terms of prior knowledge. The parameters \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) can be seen as counts of prior observations of heads and tails, respectively. This makes it a natural choice when we have prior information or beliefs about the likelihood of different outcomes, and want to update them as new data comes in.

Note: I highly suggest taking a look at the Beta distribution graph. As \(\alpha\) increases, the distribution tends to skew towards higher values of \(\theta\) (closer to 1), reflecting a higher likelihood of success. On the other hand, as \(\beta\) increases, the distribution skews towards lower values of \(\theta\) (closer to 0), indicating a higher likelihood of failure. If \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are equal, the distribution is symmetric and uniform, reflecting no prior preference between the two outcomes.

After observing data \(D = (\text{H, H, T, T, T, H, ...})\), where \(n_h\) is the number of heads and \(n_t\) is the number of tails, we combine the prior and likelihood to obtain the posterior distribution.

The likelihood function, based on the observed data, is:

\[L(\theta) = p(D \mid \theta) = \theta^{n_h} (1 - \theta)^{n_t}.\]Combining the prior and likelihood, the posterior density is:

\[p(\theta \mid D) \propto p(\theta) \cdot L(\theta),\]which simplifies to:

\[p(\theta \mid D) \propto \theta^{h - 1} (1 - \theta)^{t - 1} \cdot \theta^{n_h} (1 - \theta)^{n_t}.\]Simplifying further, we get:

\[p(\theta \mid D) \propto \theta^{h - 1 + n_h} (1 - \theta)^{t - 1 + n_t}.\]This posterior distribution is also a Beta distribution:

\[\theta \mid D \sim \text{Beta}(h + n_h, t + n_t).\]Interpreting the Posterior

The posterior distribution shows how our prior beliefs are updated by the observed data:

- The prior \(\text{Beta}(h, t)\) initializes our counts with \(h\) heads and \(t\) tails.

- The posterior \(\text{Beta}(h + n_h, t + n_t)\) updates these counts by adding the observed \(n_h\) heads and \(n_t\) tails.

For example, if our prior belief was \(\text{Beta}(2, 2)\) (a uniform prior), and we observed \(n_h = 3\) heads and \(n_t = 1\) tails, the posterior would be:

\[\text{Beta}(2 + 3, 2 + 1) = \text{Beta}(5, 3).\]This reflects our updated belief about the probability of heads after observing the data.

Wrapping Up

In this blog, we explored the essence of Bayesian statistics, focusing on how priors, likelihoods, and posteriors interact to update our beliefs. Using the coin-flipping example, we demonstrated key Bayesian tools like the Beta distribution and how to compute posterior updates. Also, as we mentioned, there’s one more important reason for choosing the Beta distribution—its technical term is conjugate priors. In the next blog, we’ll dive deeper into this concept and explore Bayesian point estimates, comparing them to the frequentist MLE estimate. Stay tuned as we continue to build intuition and delve further into Bayesian inference! 👋

References

- Bayesian Statistics