Generalized Linear Models Explained - Leveraging MLE for Regression and Classification

When building machine learning models, one of the most important tasks is estimating the parameters of a model in a way that best explains the observed data. This is where the principle of Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) comes into play. MLE provides a rigorous framework for parameter estimation, grounded in probability theory, and is widely used across regression, classification, and beyond.

Suppose we have a probabilistic model and a dataset \(D\). The central question is: how do we estimate the parameters \(\theta\) of the model? According to MLE, we should choose \(\theta\) to maximize the likelihood of the observed data. Formally, the likelihood function is defined as:

\[L(\theta) \stackrel{\text{def}}{=} p(D; \theta),\]which captures how likely the dataset \(D\) is, given the model parameters \(\theta\).

If the dataset consists of \(N\) independent and identically distributed (iid) examples, the likelihood simplifies to a product of individual data likelihoods:

\[L(\theta) = \prod_{n=1}^{N} p\left(y^{(n)} \mid x^{(n)}; \theta\right)\]While this expression is mathematically correct, the product of many probabilities can be unwieldy. To simplify the computation, we typically work with the log-likelihood, \(\ell(\theta)\), which is simply the natural logarithm of the likelihood:

\[\ell(\theta) \stackrel{\text{def}}{=} \log L(\theta) = \sum_{n=1}^{N} \log p\left(y^{(n)} \mid x^{(n)}; \theta\right)\]Maximizing \(\ell(\theta)\) is equivalent to maximizing \(L(\theta)\), as the logarithm is a monotonic function. Alternatively, minimizing the negative log-likelihood (NLL) is a common approach, as it frames the problem as a minimization task.

MLE for Linear Regression

To make these concepts more concrete, let’s see how MLE applies to a simple and widely known model: linear regression.

In linear regression, we assume the output \(Y\) is conditionally Gaussian given the input \(X\). Specifically,

\[Y \mid X = x \sim \mathcal{N}(\theta^\top x, \sigma^2),\]where \(\theta^\top x\) is the mean and \(\sigma^2\) is the variance of the Gaussian distribution.

The log-likelihood for this model can be written as:

\[\ell(\theta) \stackrel{\text{def}}{=} \log L(\theta) = \log \prod_{n=1}^{N} p\left(y^{(n)} \mid x^{(n)}; \theta\right) = \sum_{n=1}^{N} \log p\left(y^{(n)} \mid x^{(n)};\theta\right)\]Substituting the Gaussian probability density function into the equation, we get:

\[\ell(\theta) = \sum_{n=1}^{N} \log \left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} \exp\left( -\frac{\left(y^{(n)} - \theta^\top x^{(n)}\right)^2}{2\sigma^2} \right) \right)\]Simplifying further, the log-likelihood becomes:

\[\ell(\theta) = N \log \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} - \frac{1}{2\sigma^2} \sum_{n=1}^{N} \left(y^{(n)} - \theta^\top x^{(n)}\right)^2\]Notice that the first term, \(N \log \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}}\), is independent of \(\theta\). This means that to maximize \(\ell(\theta)\), we only need to minimize the second term, which is proportional to the sum of squared residuals.

This brings us to an important insight: maximizing the log-likelihood in linear regression is equivalent to minimizing the squared error.

Deriving the Gradient of the Log-Likelihood

To find the parameters that maximize the log-likelihood, we compute its gradient with respect to \(\theta\) and set it to zero. From our earlier expression for \(\ell(\theta)\):

\[\ell(\theta) = N \log \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} - \frac{1}{2\sigma^2} \sum_{n=1}^{N} \left(y^{(n)} - \theta^\top x^{(n)}\right)^2,\]the gradient with respect to \(\theta_i\), the \(i\)-th parameter, is:

\[\frac{\partial \ell}{\partial \theta_i} = -\frac{1}{\sigma^2} \sum_{n=1}^{N} \left(y^{(n)} - \theta^\top x^{(n)}\right) x_i^{(n)}\]Setting \(\frac{\partial \ell}{\partial \theta_i} = 0\) gives us the familiar normal equations for linear regression, which are typically solved to find the optimal \(\theta\).

This yields:

\[-\frac{1}{\sigma^2} \sum_{n=1}^{N} \left(y^{(n)} - \theta^\top x^{(n)}\right) x_i^{(n)} = 0\]Multiplying both sides by \(\sigma^2\) gives:

\[\sum_{n=1}^{N} \left(y^{(n)} - \theta^\top x^{(n)}\right) x_i^{(n)} = 0\]We can write the equation in matrix form as:

\[\mathbf{X}^\top \left( \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \theta \right) = 0\]Rewriting the equation:

\[\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X} \theta = 0\]Rearranging gives the normal equation:

\[\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X} \theta = \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{y}\]Solving for \(\theta\):

\[\theta = \left( \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X} \right)^{-1} \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{y}\]Through this derivation, we’ve established a key connection between the probabilistic interpretation of linear regression and the classical squared error minimization. The principle of MLE not only provides a mathematically grounded way to estimate parameters but also reveals the assumptions underlying different models.

What’s fascinating is that this approach generalizes beyond regression. For instance, in classification tasks, MLE leads to the cross-entropy loss. This will be the focus of the next section, where we’ll explore how MLE ties into classification problems and the role of log-loss in optimizing model parameters.

From Linear to Logistic Regression: Expanding the Scope of MLE

In the previous section, we explored how the Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) principle naturally connects with linear regression. We saw that linear regression assumes the target \(Y \vert X = x\) follows a Gaussian distribution, and maximizing the likelihood aligns with minimizing the squared loss.

But is the Gaussian assumption always valid? Not necessarily. For example, in classification tasks where \(Y\) takes on discrete values (e.g., 0 or 1), assuming a Gaussian distribution is inappropriate. This raises an important question: can we use the same MLE-based modeling approach for tasks beyond regression?

The answer is yes, and this brings us to logistic regression, which is tailored for classification tasks.

Logistic Regression: Assumptions and Foundations

Consider a binary classification problem where the target \(Y \in \{0, 1\}\). What should the conditional distribution of \(Y\) given \(X = x\) look like? For logistic regression, we model \(p(y \mid x)\) using a Bernoulli distribution:

\[p(y \mid x) = h(x)^y (1 - h(x))^{1-y},\]where \(h(x) \in (0, 1)\) represents the probability \(p(y = 1 \mid x)\).

Parameterizing \(h(x)\):

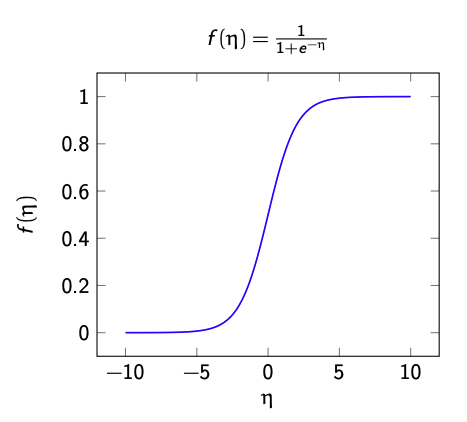

In linear regression, the mean \(\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X = x]\) was parameterized as \(\theta^\top x\). However, for classification, \(h(x)\) must map the linear predictor \(\theta^\top x\) (which lies in \(\mathbb{R}\)) to the interval \((0, 1)\). To achieve this, we use the logistic function:

\[f(\eta) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-\eta}}, \quad \text{where } \eta = \theta^\top x\]Thus, the probability \(p(y \mid x)\) becomes:

\[p(y \mid x) = \text{Bernoulli}(f(\theta^\top x)),\]or equivalently:

\[p(y = 1 \mid x) = f(\theta^\top x), \quad p(y = 0 \mid x) = 1 - f(\theta^\top x)\][any reason why bernoulli?]

Why do we use the Bernoulli distribution in logistic regression?

In logistic regression, the target variable \(Y\) is binary, taking values in \(\{0, 1\}\), making the Bernoulli distribution a natural choice. The Bernoulli distribution models the probability of success (1) or failure (0) in a single trial.

We model the conditional probability \(p(y \mid x)\) using the logistic function, which ensures that the predicted probabilities lie in the interval \((0, 1)\):

\[p(y = 1 \mid x) = f(\theta^\top x), \quad p(y = 0 \mid x) = 1 - f(\theta^\top x),\]where \(f(\eta) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-\eta}}\) is the logistic function. The Bernoulli distribution is then used to model the binary outcomes given these probabilities.

Interpreting the Logistic Function

The logistic function is smooth and monotonically increasing, mapping any real-valued input to a value in the range \((0, 1)\). It has the characteristic “S-shape” and is particularly useful for modeling probabilities.

One interesting property of the logistic function is its connection to the log-odds. For logistic regression:

\[\log \frac{p(y = 1 \mid x)}{p(y = 0 \mid x)} = \theta^\top x\]This shows that the log-odds (or logit) of \(y = 1\) depend linearly on the input \(x\). Moreover, the decision boundary, where \(p(y = 1 \mid x) = p(y = 0 \mid x) = 0.5\), is defined by \(\theta^\top x = 0\), making it a linear decision boundary.

MLE for Logistic Regression

As with linear regression, the parameters \(\theta\) in logistic regression are estimated by maximizing the conditional log-likelihood:

\[\ell(\theta) = \sum_{n=1}^{N} \log p\left(y^{(n)} \mid x^{(n)}; \theta\right)\]For a Bernoulli-distributed \(y\), substituting \(p(y \mid x)\):

\[\ell(\theta) = \sum_{n=1}^{N} \left[ y^{(n)} \log f(\theta^\top x^{(n)}) + (1 - y^{(n)}) \log (1 - f(\theta^\top x^{(n)})) \right]\]Unlike linear regression, this log-likelihood does not have a closed-form solution for \(\theta\). However, it is concave, meaning that optimization techniques like gradient ascent can efficiently find the unique optimal solution.

Gradient Ascent for Logistic Regression

The gradient of the log-likelihood \(\ell(\theta)\) with respect to \(\theta_i\) (the \(i\)-th parameter) is given by:

\[\frac{\partial \ell}{\partial \theta_i} = \sum_{n=1}^{N} \left( y^{(n)} - f(\theta^\top x^{(n)}) \right) x_i^{(n)}\]Derivation of the above form:

Math Review: Chain Rule

If \(z\) depends on \(y\), which itself depends on \(x\), e.g., \(z = (y(x))^2\), then:

\[\frac{dz}{dx} = \frac{dz}{dy} \frac{dy}{dx}\]Likelihood for a Single Example:

\[\ell^n = y^{(n)} \log f(\theta^\top x^{(n)}) + (1 - y^{(n)}) \log(1 - f(\theta^\top x^{(n)}))\]The gradient with respect to \(\theta_i\) is:

\[\frac{\partial \ell^n}{\partial \theta_i} = \frac{\partial \ell^n}{\partial f^n} \frac{\partial f^n}{\partial \theta_i}\]Using the chain rule:

\[= \left(\frac{y^{(n)}}{f^n} - \frac{1 - y^{(n)}}{1 - f^n}\right) \frac{\partial f^n}{\partial \theta_i}\]Simplify:

\[= \left(\frac{y^{(n)}}{f^n} - \frac{1 - y^{(n)}}{1 - f^n}\right) \left(f^n (1 - f^n) x_i^{(n)}\right)\] \[= \left(y^{(n)} - f^n\right) x_i^{(n)}.\]The full gradient is thus:

\[\frac{\partial \ell}{\partial \theta_i} = \sum_{n=1}^{N} \left(y^{(n)} - f(\theta^\top x^{(n)})\right) x_i^{(n)}.\]This gradient looks strikingly similar to that of linear regression, except for the presence of the logistic function \(f(\cdot)\).

Using this gradient, we iteratively update the parameters using gradient ascent:

\[\theta \leftarrow \theta + \alpha \nabla_\theta \ell(\theta),\]where \(\alpha\) is the learning rate.

Note the distinction: since the function is concave, we apply gradient ascent rather than descent.

A Comparison: Linear vs Logistic Regression

Here’s a side-by-side comparison to highlight the similarities and differences:

| Feature | Linear Regression | Logistic Regression |

|---|---|---|

| Input combination | \(\theta^\top x\) (linear) | \(\theta^\top x\) (linear) |

| Output | Real-valued | Categorical (0 or 1) |

| Conditional distribution | Gaussian | Bernoulli |

| Transfer function \(f(\theta^\top x)\) | Identity | Logistic |

| Mean \(\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X = x; \theta]\) | \(f(\theta^\top x)\) | \(f(\theta^\top x)\) |

The main difference lies in the conditional distribution of \(Y\) and the transfer function \(f(\cdot)\), which maps \(\theta^\top x\) to the appropriate range for each model.

Generalizing Logistic Regression

The principles behind logistic regression can be extended to handle other types of outputs, such as counts or probabilities for multiple classes. This generalization leads to the broader family of generalized linear models (GLMs).

Steps for Generalized Regression Models

- Task: Given \(x\), predict \(p(y \mid x)\).

- Modeling:

- Choose a parametric family of distributions \(p(y; \theta)\) with parameters \(\theta \in \Theta\).

- Choose a transfer function that maps a linear predictor in \(\mathbb{R}\) to \(\Theta\):

-

Learning: Use MLE to estimate the parameters:

\[\hat{\theta} = \arg\max_\theta \log p(D; \hat{\theta})\] -

Inference: For prediction, map \(x\) through the learned transfer function:

\[x \mapsto f(w^\top x)\]

In the next section, we’ll dive deeper into these generalized models, exploring their flexibility and application to diverse prediction tasks.

Extending Generalized Linear Models: From Poisson to Multinomial Logistic Regression

In our journey through generalized linear models (GLMs), we’ve seen how logistic regression extends MLE principles to classification tasks. Now, let’s explore other use cases where GLMs shine, including Poisson regression for count-based predictions and multinomial logistic regression for multiclass classification.

Example: Poisson Regression

Imagine we want to predict the number of people entering a New York restaurant during lunchtime. What features could help? Time of day, day of the week, weather conditions, or nearby events might all be relevant. Importantly, the target variable \(Y\), representing the number of visitors, is a non-negative integer: \(Y \in \{0, 1, 2, \dots\}\).

Why Use the Poisson Distribution?

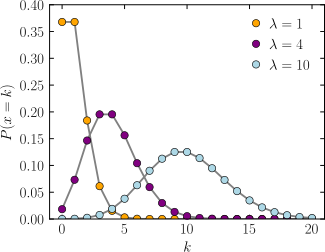

The Poisson distribution is a natural choice for modeling count data. A random variable \(Y \sim \text{Poisson}(\lambda)\) has the probability mass function:

\[p(Y = k; \lambda) = \frac{\lambda^k e^{-\lambda}}{k!}, \quad k \in \{0, 1, 2, \dots\},\]where \(\lambda > 0\) is the rate parameter. The expected value \(\mathbb{E}[Y] = \lambda\), making \(\lambda\) both the mean and variance of \(Y\).

What Does the Poisson Distribution Mean, Intuitively?

The Poisson distribution can be understood through a simple analogy: imagine standing at a bus stop.

- The Events: Each bus that arrives at the stop is an “event.”

- Constant Rate: On average, buses arrive every 10 minutes, meaning we expect about 6 buses per hour. This average rate, \(\lambda = 6\), is constant.

- Independence: The arrival of one bus doesn’t affect when the next one will come (events are independent).

Now, if you wait at the bus stop for an hour, the Poisson distribution models the probability of seeing exactly 5, 6, or 7 buses in that time. While the average is 6 buses, randomness may cause the actual count to vary, with probabilities decreasing for more extreme deviations (e.g., 0 buses or 12 buses in an hour are unlikely).

This shows how the Poisson distribution captures both the expected rate (\(\lambda\)) and the variability in the number of events.

Constructing the Poisson Regression Model

We assume \(Y \mid X = x \sim \text{Poisson}(\lambda)\). The challenge is to ensure \(\lambda\), the rate parameter, is positive. This is achieved using a transfer function \(f\):

\[x \mapsto w^\top x \quad \text{(linear predictor in } \mathbb{R} \text{)} \mapsto \lambda = f(w^\top x) \quad \text{(rate parameter in } (0, \infty) \text{)}.\]The standard transfer function is the exponential function:

\[f(w^\top x) = e^{w^\top x}\]Log-Likelihood for Poisson Regression

Given a dataset \(D = \{(x_1, y_1), \dots, (x_n, y_n)\}\), the log-likelihood is:

\[\log p(y_i; \lambda_i) = \left[y_i \log \lambda_i - \lambda_i - \log(y_i!)\right]\] \[\log p(D; w) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left[ y_i \log f(w^\top x_i) - f(w^\top x_i) - \log(y_i!) \right],\]where \(f(w^\top x_i) = e^{w^\top x_i}\). Substituting \(\lambda_i\), we get:

\[\log p(D; w) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left[ y_i (w^\top x_i) - e^{w^\top x_i} - \log(y_i!) \right]\]As with logistic regression, the likelihood is concave, so gradient-based methods can efficiently optimize \(w\).

Gradient for Poisson Regression

To optimize the log-likelihood, we compute its gradient with respect to the weight vector \(w\).

The gradient is:

\[\frac{\partial \log p(D; w)}{\partial w} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left[ y_i x_i - e^{w^\top x_i} x_i \right]\]Factoring out common terms, we get:

\[\frac{\partial \log p(D; w)}{\partial w} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i \left[ y_i - e^{w^\top x_i} \right]\]The gradient indicates the update direction for \(w\), with each term capturing the difference between the observed count \(y_i\) and the predicted count \(e^{w^\top x_i}\), weighted by the feature vector \(x_i\). Gradient ascent can then be used to maximize the log-likelihood, as the likelihood is concave for Poisson regression. Again, notice how similar the gradient is to the other problems we’ve explored so far—the transfer function differs in each case.

Example: Multinomial Logistic Regression

Next, let’s tackle multiclass classification, where the target \(Y \in \{1, 2, \dots, k\}\) spans multiple categories. Logistic regression’s Bernoulli distribution extends to the categorical distribution, which is parameterized by a probability vector \(\theta = (\theta_1, \dots, \theta_k)\). For valid probabilities:

\[\sum_{i=1}^{k} \theta_i = 1, \quad \theta_i \geq 0 \text{ for all } i.\]For a given \(y \in \{1, \dots, k\}\):

\[p(y) = \theta_y.\]What Does the Categorical Distribution Mean, Intuitively?

The categorical distribution assigns a probability to each class. For a given input \(x\), we want to predict the probability of each class \(y\) belonging to the target set. The probability of the class \(y\) is \(\theta_y\), where \(\theta_y\) is the component of the probability vector corresponding to the class \(y\). This allows us to perform multiclass classification by selecting the class with the highest probability.

\[p(y) = \theta_y.\]Constructing the Multinomial Logistic Regression Model

The key idea in multinomial logistic regression is to compute a linear score for each class. For a given input vector \(x\), we compute a vector of scores \(s \in \mathbb{R}^k\) for all classes:

\[s = (w_1^\top x, \dots, w_k^\top x),\]where \(w_i\) represents the weight vector associated with class \(i\). These scores are then transformed using the softmax function to produce valid probabilities. The softmax function is defined as:

\[\text{softmax}(s)_i = \frac{e^{s_i}}{\sum_{j=1}^{k} e^{s_j}} \quad \text{for } i = 1, \dots, k.\]The softmax function ensures that the resulting probabilities form a valid probability distribution, satisfying:

\[\sum_{i=1}^{k} \theta_i = 1, \quad \theta_i \geq 0 \text{ for all } i.\]Log-Likelihood for Multinomial Logistic Regression

Given a dataset \(D = \{(x_1, y_1), \dots, (x_n, y_n)\}\), the log-likelihood of the model is the sum of the log probabilities for the true classes. The log-likelihood is given by:

\[\log p(D; W) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \log \theta_{y_i},\]where \(\theta_{y_i} = \text{softmax}(W^\top x_i)_{y_i}\). The parameters \(W\) are learned by maximizing the log-likelihood using gradient-based optimization methods.

Note: Don’t be misled by the use of theta and softmax notations. The way this is mentioned can be confusing. For now, let’s proceed with caution.

Gradient for Multinomial Logistic Regression

To optimize the parameters \(W\), we compute the gradient of the log-likelihood with respect to \(W\).

Step-by-Step Derivation

-

Log-Likelihood for Multinomial Logistic Regression:

The log-likelihood for the dataset \(D = \{(x_1, y_1), \dots, (x_n, y_n)\}\) is:

\[\log p(D; W) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \log \theta_{y_i},\]where \(\theta_{y_i} = \text{softmax}(W^\top x_i)_{y_i}\) is the predicted probability of the true class \(y_i\) for the \(i\)-th data point.

-

Softmax Function:

The softmax function for class \(j\) is given by:

\[\theta_j(x_i; W) = \frac{e^{w_j^\top x_i}}{\sum_{k=1}^{k} e^{w_k^\top x_i}}.\] -

Log-Likelihood Expansion:

Substituting the softmax expression into the log-likelihood:

\[\log p(D; W) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \log \left( \frac{e^{w_{y_i}^\top x_i}}{\sum_{k=1}^{k} e^{w_k^\top x_i}} \right),\]which simplifies to:

\[\log p(D; W) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left( w_{y_i}^\top x_i - \log \left( \sum_{k=1}^{k} e^{w_k^\top x_i} \right) \right).\] -

Gradient of the Log-Likelihood:

The gradient of the log-likelihood with respect to the weight vector \(w_j\) is computed by differentiating each term in the log-likelihood expression:

-

The derivative of the first term, \(w_{y_i}^\top x_i\), with respect to \(w_j\) is simply \(x_i\) when \(y_i = j\) and 0 otherwise.

-

The second term involves the log-sum-exp, and its derivative with respect to \(w_j\) is:

\[\nabla_{w_j} \log \left( \sum_{k=1}^{k} e^{w_k^\top x_i} \right) = \theta_j(x_i; W) \cdot x_i.\]

-

-

Final Gradient Expression:

Combining the two terms, the gradient of the log-likelihood with respect to \(w_j\) is:

\[\nabla_{w_j} \log p(D; W) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left( \mathbf{1}_{\{y_i = j\}} - \theta_j(x_i; W) \right) x_i,\]where \(\mathbf{1}_{\{y_i = j\}}\) is the indicator function that is 1 if the true class \(y_i\) equals \(j\), and 0 otherwise.

This gradient is used to adjust the weight vectors during training to improve the model’s predictions.

Review: Recipe for Conditional Models

GLMs provide a unified approach for constructing conditional models. Here’s a quick recipe:

- Define the Input and Output Space: Start with the features \(x\) and target \(y\).

- Choose an Output Distribution: Based on the nature of \(y\), select an appropriate probability distribution \(p(y \mid x; \theta)\).

- Select a Transfer Function: Map the linear predictor \(w^\top x\) into the required range of the distribution parameters.

- Optimize via MLE: Estimate \(\theta\) by maximizing the log-likelihood using gradient-based methods.

This framework, called generalized linear models, can be adapted for a wide range of prediction tasks.

Before we wrap up, did we overlook something? Ah, yes—let’s revisit the log-sum-exp function and its significance.

Log-Sum-Exp Function

The log-sum-exp (LSE) function is a mathematical expression used frequently in machine learning and statistics, particularly in contexts involving probabilities and normalization. It is defined as:

\[\text{LSE}(s) = \log \left( \sum_{k=1}^K e^{s_k} \right),\]where \(s = (s_1, s_2, \dots, s_K)\) is a vector of real-valued scores.

Key Properties of Log-Sum-Exp

-

Smooth Maximum Approximation

\[\text{LSE}(s) \approx \max(s_k)\]

The log-sum-exp function can be thought of as a “soft maximum” of the elements in \(s\) because, for large values of \(s_k\), the largest term dominates the sum: -

Numerical Stability

\[\text{LSE}(s) = \log \left( \sum_{k=1}^K e^{s_k - \max(s)} \right) + \max(s),\]

To ensure numerical stability when computing \(e^{s_k}\) for large values of \(s_k\), the log-sum-exp function is often rewritten as:where \(\max(s)\) is the maximum value in \(s\). This adjustment ensures that the exponentials remain within a manageable range. Check why it’s written this way in the referenced resource; I highly recommend it.

Log-Sum-Exp in Multinomial Logistic Regression

In multinomial logistic regression, the log-sum-exp term naturally arises when computing the log-likelihood. The predicted probabilities are computed using the softmax function:

\[\theta_j(x_i; W) = \frac{e^{w_j^\top x_i}}{\sum_{k=1}^{K} e^{w_k^\top x_i}}\]The denominator of the softmax involves a sum of exponentials. Taking the logarithm of the denominator gives the log-sum-exp term:

\[\log \left( \sum_{k=1}^K e^{w_k^\top x_i} \right)\]This term normalizes the probabilities so that they sum to 1 across all classes.

Derivative of Log-Sum-Exp

The derivative of the log-sum-exp function with respect to a specific score \(s_j\) is:

\[\frac{\partial}{\partial s_j} \log \left( \sum_{k=1}^K e^{s_k} \right) = \frac{e^{s_j}}{\sum_{k=1}^K e^{s_k}}\]This is equivalent to the probability assigned to class \(j\) by the softmax function:

\[\frac{\partial}{\partial s_j} \log \left( \sum_{k=1}^K e^{s_k} \right) = \text{softmax}(s)_j.\]In the case of multinomial logistic regression, where \(s_j = w_j^\top x_i\), the derivative with respect to \(w_j\) is:

\[\nabla_{w_j} \log \left( \sum_{k=1}^K e^{w_k^\top x_i} \right) = \theta_j(x_i; W) \cdot x_i,\]where \(\theta_j(x_i; W) = \text{softmax}(W^\top x_i)_j\) is the predicted probability for class \(j\).

Still, Why the Use of Log-Sum-Exp

In multinomial logistic regression, we use the softmax function to convert the raw class scores (logits) into probabilities. The softmax function itself involves summing the exponentials of the scores, not the log-sum-exp.

However, when calculating the log-likelihood of the model during optimization, we encounter the log-sum-exp function. The log-sum-exp is used in the log-likelihood to handle the sum of the exponentials in a numerically stable way. It’s primarily used to:

- Avoid overflow and underflow: When working with large or small exponentiated values (as in the softmax function), exponentiation can cause numerical instability. The log-sum-exp helps stabilize these computations.

- Ensure proper normalization: In the context of the softmax function, it ensures the sum of the probabilities is 1, making them valid probabilities for classification.

In summary, while softmax uses the sum of exponentials, the log-sum-exp appears in the log-likelihood computation to stabilize the logarithmic transformation, enabling proper optimization.

Analogy for the Log-Sum-Exp Function

Imagine you’re at a sports competition with several players, and their scores are exponentially amplified (think of \(e^{s_k}\) as the “hype” around each player’s performance). The log-sum-exp function acts like a judge summarizing all the scores into a single value that reflects the overall competition, but with a bias toward the top performers.

- The “log” compresses the scale, keeping the summary manageable.

- The “sum” captures the contributions of all players, not just the best one.

- The “exp” amplifies the impact of the highest scores, making it feel like a weighted average that leans toward the standout performers.

In short, the log-sum-exp is like a “soft maximum”: it highlights the best, considers the rest, and ensures the result is stable and interpretable.

If you’re having trouble with this analogy, go through the example in the reference. It’ll help clarify things.

Alright, it’s time to wrap this up. In the next section, we’ll dive into another type of probabilistic modeling: generative models. We’ll explore what they are and how they work. Stay tuned, and see you there!