Multivariate Gaussian Distribution and Naive Bayes

When analyzing data in higher dimensions, we often encounter scenarios where input features are not independent. In such cases, the Multivariate Gaussian Distribution provides a robust probabilistic framework to model these relationships. It extends the familiar univariate Gaussian distribution to multiple dimensions, enabling us to capture dependencies and correlations between variables effectively.

Understanding the Multivariate Gaussian Distribution

A multivariate Gaussian distribution is defined as:

\[x \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu, \Sigma),\]where \(\mu\) is the mean vector, and \(\Sigma\) is the covariance matrix. Its probability density function is given by:

\[p(x) = \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{d/2} |\Sigma|^{1/2}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2}(x - \mu)^\top \Sigma^{-1} (x - \mu)\right),\]Here, \(d\) represents the dimensionality of the input \(x\), \(\vert \Sigma \vert\) denotes the determinant of the covariance matrix, and \(\Sigma^{-1}\) is its inverse.

The term \((x - \mu)^\top \Sigma^{-1} (x - \mu)\) is referred to as the Mahalanobis distance, which measures the distance of a point \(x\) from the mean \(\mu\). Unlike the Euclidean distance, the Mahalanobis distance normalizes for differences in variances and accounts for correlations between the dimensions. This normalization makes it particularly useful in multivariate data analysis.

Intuition and Analogy for Multivariate Gaussian

Think of the multivariate Gaussian distribution as a 3D bell-shaped curve (or higher-dimensional equivalent) where:

- The peak of the bell is at \(\mu\), the mean vector.

- The spread of the bell in different directions is determined by \(\Sigma\), the covariance matrix. It stretches or compresses the curve along certain axes depending on the variances and correlations.

Analogy: A Weighted Balloon

Imagine a balloon filled with air. If the balloon is perfectly spherical, it represents a distribution where all dimensions are independent and have the same variance (this corresponds to \(\Sigma\) being a diagonal matrix with equal entries).

Now, if you squeeze the balloon in one direction:

- It elongates in one direction and compresses in another. This reflects correlations between dimensions in the data, encoded by the off-diagonal elements of \(\Sigma\).

- The shape of the balloon changes, and distances (like Mahalanobis distance) now account for these correlations, unlike Euclidean distance.

How to Think About Mahalanobis Distance

The Mahalanobis distance:

\[d_M(x) = \sqrt{(x - \mu)^\top \Sigma^{-1} (x - \mu)}\]can be understood as the distance from a point \(x\) to the center \(\mu\), scaled by the shape and orientation of the distribution:

-

Scaling by Variance: In directions where the variance is large (the distribution is “spread out”), the Mahalanobis distance will consider points farther from the mean as less unusual. Conversely, in directions where variance is small, even small deviations from the mean are considered significant.

-

Accounting for Correlations: If two dimensions are correlated, the Mahalanobis distance adjusts for this by using the covariance matrix \(\Sigma\). The covariance matrix captures both the variances of individual dimensions and the relationships (correlations) between them.

Role of the Inverse Covariance Matrix:

The term \(\Sigma^{-1}\) (the inverse of the covariance matrix) in the Mahalanobis distance ensures that the contribution of each dimension is scaled appropriately. For example:

- If two dimensions are strongly correlated, deviations along one dimension are partially “explained” by deviations along the other. The Mahalanobis distance reduces the weight of such deviations, treating them as less unusual.

- Conversely, if two dimensions are uncorrelated, the deviations are treated independently.

Example:

In a dataset of height and weight, a taller-than-average person is likely to weigh more than average. The covariance matrix captures this relationship, and \(\Sigma^{-1}\) adjusts the distance calculation to reflect that such deviations are expected. Without this adjustment (as in Euclidean distance), the relationship would be ignored, leading to an overestimation of the “unusualness” of the point.

Returning to the Balloon Analogy,

The Mahalanobis distance incorporates the “shape” of the balloon (determined by \(\Sigma\)) to measure distances:

Shape and Scaling:

- A spherical balloon corresponds to a covariance matrix where all dimensions are independent and have equal variance. In this case, the Mahalanobis distance reduces to the Euclidean distance.

- A stretched or compressed balloon reflects correlations or differences in variance. The Mahalanobis distance scales the contribution of each dimension based on the covariance structure, ensuring that distances are measured relative to the shape of the distribution.

How It Works:

- Points on the surface of the balloon correspond to a Mahalanobis distance of 1, regardless of the balloon’s shape. This is because the Mahalanobis distance normalizes for the stretching or compressing of the balloon in different directions.

- Mathematically, this is achieved by transforming the space using \(\Sigma^{-1}\), effectively “flattening” the correlations and variances. In this transformed space, the balloon becomes a perfect sphere, and distances are measured uniformly.

These adjustments make the Mahalanobis distance a powerful metric for detecting outliers and understanding the distribution of data in a multivariate context.

If you’re still unsure about the concept, let’s walk through an example and explore it together.

1. Covariance Matrix:

For a dataset with two variables, say height (\(x_1\)) and weight (\(x_2\)), the covariance matrix \(\Sigma\) looks like this:

\[\Sigma = \begin{pmatrix} \sigma_{11} & \sigma_{12} \\ \sigma_{21} & \sigma_{22} \end{pmatrix}\]Where:

- \(\sigma_{11}\) is the variance of height (\(x_1\)).

- \(\sigma_{22}\) is the variance of weight (\(x_2\)).

- \(\sigma_{12} = \sigma_{21}\) is the covariance between height and weight.

2. Inverse Covariance Matrix:

The inverse of the covariance matrix \(\Sigma^{-1}\) is used to “normalize” the data and account for correlations. The inverse of a 2x2 matrix is given by:

\[\Sigma^{-1} = \frac{1}{\text{det}(\Sigma)} \begin{pmatrix} \sigma_{22} & -\sigma_{12} \\ -\sigma_{21} & \sigma_{11} \end{pmatrix}\]Where the determinant of the covariance matrix is:

\[\text{det}(\Sigma) = \sigma_{11} \sigma_{22} - \sigma_{12}^2\]3. Example: Correlated Data (Height and Weight)

Suppose we have a dataset of heights and weights, and the covariance matrix looks like this:

\[\Sigma = \begin{pmatrix} 100 & 80 \\ 80 & 200 \end{pmatrix}\]This means:

- The variance of height (\(\sigma_{11}\)) is 100.

- The variance of weight (\(\sigma_{22}\)) is 200.

- The covariance between height and weight (\(\sigma_{12} = \sigma_{21}\)) is 80, indicating a strong positive correlation between height and weight.

Now, let’s say we have a data point:

\[x = \begin{pmatrix} 180 \\ 75 \end{pmatrix}\]This means the person is 180 cm tall and weighs 75 kg. The mean of the dataset is:

\[\mu = \begin{pmatrix} 170 \\ 70 \end{pmatrix}\]3.1. Euclidean Distance (Without Accounting for Correlation)

The Euclidean distance between the data point \(x\) and the mean \(\mu\) is:

\[D_E(x) = \sqrt{(x_1 - \mu_1)^2 + (x_2 - \mu_2)^2}\]Substituting the values:

\[D_E(x) = \sqrt{(180 - 170)^2 + (75 - 70)^2} = \sqrt{10^2 + 5^2} = \sqrt{100 + 25} = \sqrt{125} \approx 11.18\]This distance doesn’t account for the correlation between height and weight. It treats the two dimensions as if they are independent, and gives a straightforward measure of how far the point is from the mean in Euclidean space.

3.2. Mahalanobis Distance (With Covariance Adjustment)

Now, let’s compute the Mahalanobis distance. First, we need to compute the inverse of the covariance matrix \(\Sigma^{-1}\).

The determinant of \(\Sigma\) is:

\[\text{det}(\Sigma) = 100 \times 200 - 80^2 = 20000 - 6400 = 13600\]So, the inverse covariance matrix is:

\[\Sigma^{-1} = \frac{1}{13600} \begin{pmatrix} 200 & -80 \\ -80 & 100 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 0.0147 & -0.0059 \\ -0.0059 & 0.0074 \end{pmatrix}\]Now, we compute the Mahalanobis distance:

\[D_M(x) = \sqrt{(x - \mu)^T \Sigma^{-1} (x - \mu)}\]Substituting the values:

\[x - \mu = \begin{pmatrix} 180 - 170 \\ 75 - 70 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 10 \\ 5 \end{pmatrix}\]Now, calculate the Mahalanobis distance:

\[D_M(x) = \sqrt{\begin{pmatrix} 10 & 5 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 0.0147 & -0.0059 \\ -0.0059 & 0.0074 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 10 \\ 5 \end{pmatrix}}\]First, multiply the vectors:

\[\begin{pmatrix} 10 & 5 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 0.0147 & -0.0059 \\ -0.0059 & 0.0074 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 10 \times 0.0147 + 5 \times (-0.0059) \\ 10 \times (-0.0059) + 5 \times 0.0074 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 0.147 - 0.0295 \\ -0.059 + 0.037 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 0.1175 \\ -0.022 \end{pmatrix}\]Now, multiply this result by the vector \(\begin{pmatrix} 10 \\ 5 \end{pmatrix}\):

\[\begin{pmatrix} 0.1175 & -0.022 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 10 \\ 5 \end{pmatrix} = 0.1175 \times 10 + (-0.022) \times 5 = 1.175 - 0.11 = 1.065\]Thus, the Mahalanobis distance is:

\[D_M(x) = \sqrt{1.065} \approx 1.03\]4. Interpretation of the Results:

- The Euclidean distance between the point and the mean was approximately 11.18. This suggests that the point is far from the mean, without considering the correlation between height and weight.

- The Mahalanobis distance is 1.03, which is much smaller. This is because the Mahalanobis distance accounts for the fact that height and weight are correlated. The deviation in weight is expected given the deviation in height, so the Mahalanobis distance treats this as less “unusual.”

Takeaways:

- Euclidean distance treats each dimension as independent, ignoring correlations, which can lead to an overestimation of how unusual a point is.

- Mahalanobis distance, by using the inverse covariance matrix \(\Sigma^{-1}\), adjusts for correlations and scales the deviations accordingly. This results in a more accurate measure of how far a point is from the mean, considering the underlying structure of the data (e.g., the correlation between height and weight in this example).

Grasping Better with Bivariate Normal Distributions

To build a deeper understanding, let’s focus on a specific case: the two-dimensional Gaussian, commonly referred to as the bivariate normal distribution.

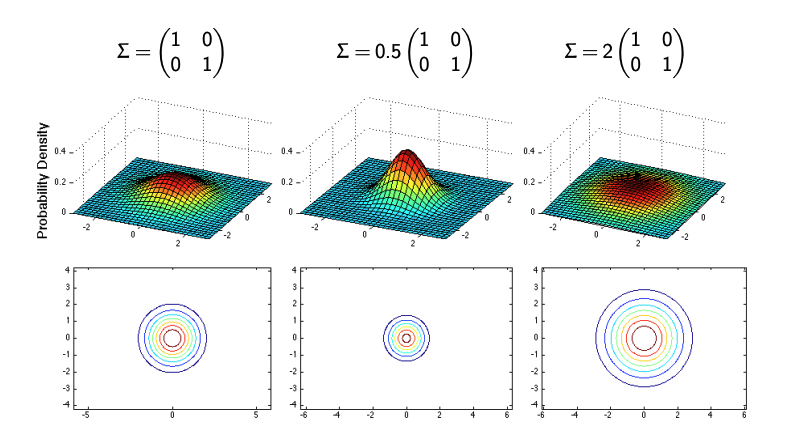

Case 1: Identity Covariance Matrix

Suppose the covariance matrix is given as:

\[\Sigma = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}.\]In this scenario, the contours of the distribution are circular. This indicates that there is no correlation between the two variables, and both have equal variances. The shape of the contours reflects the isotropic nature of the distribution.

Case 2: Scaled Identity Covariance

If we scale the covariance matrix, say:

\[\Sigma = 0.5 \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix},\]the variances of both variables decrease, resulting in smaller circular contours. Conversely, if we scale it up:

\[\Sigma = 2 \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix},\]the variances increase, leading to larger circular contours. This demonstrates how scaling the covariance matrix affects the spread of the distribution.

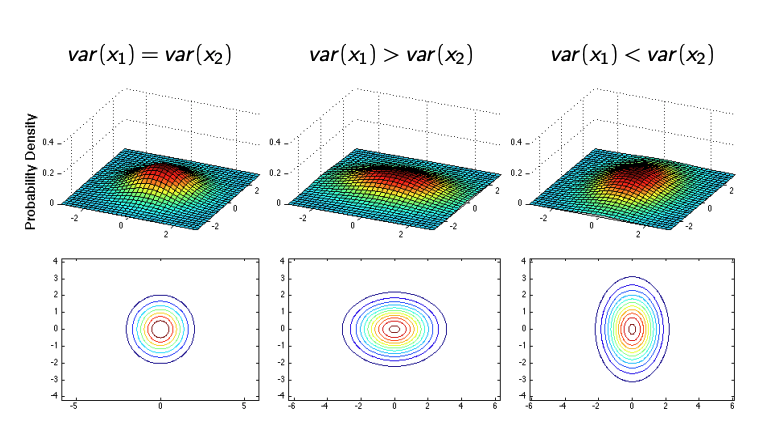

Case 3: Anisotropic Variance

When the variances of the variables are different, such as when \(\text{var}(x_1) \neq \text{var}(x_2)\), the contours take on an elliptical shape. The orientation and eccentricity of the ellipse are determined by the relative variances along each axis.

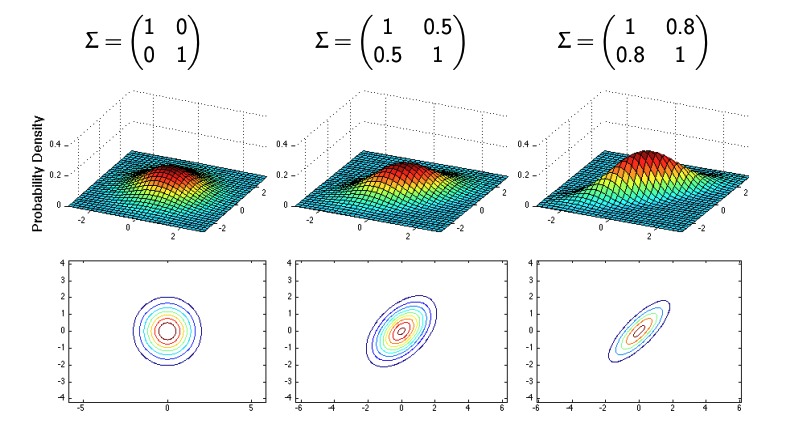

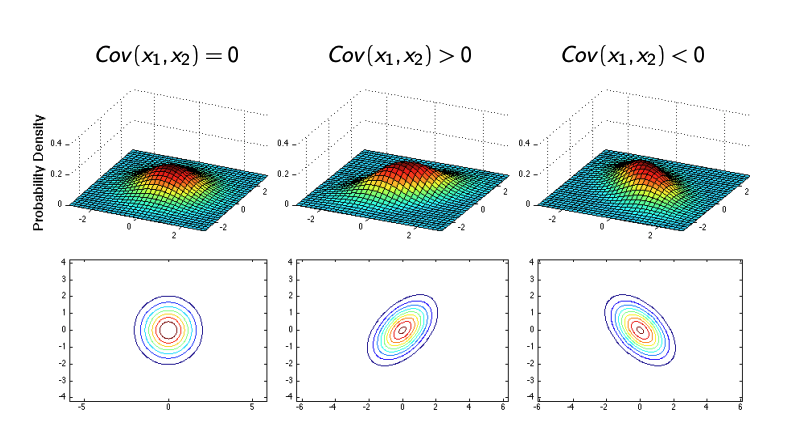

Case 4: Correlated Variables

Correlation between variables introduces an additional layer of complexity.

For instance, if:

\[\Sigma = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & \rho \\ \rho & 1 \end{bmatrix},\]where \(\rho\) is the correlation coefficient:

- When \(\rho > 0\), the variables are positively correlated, and the ellipse tilts along the diagonal.

- When \(\rho < 0\), the variables are negatively correlated, and the ellipse tilts in the opposite direction.

- When \(\rho = 0\), the variables remain uncorrelated, resulting in circular or axis-aligned ellipses.

Gaussian Bayes Classifier

The Gaussian Bayes Classifier (GBC) extends the Gaussian framework to classification tasks. It assumes that the conditional distribution \(p(x \vert y)\) follows a multivariate Gaussian distribution. Mathematically, for a class \(k\):

\[p(x|t = k) = \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{d/2} |\Sigma_k|^{1/2}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2}(x - \mu_k)^\top \Sigma_k^{-1} (x - \mu_k)\right),\]where each class \(k\) has its own mean vector \(\mu_k\) and covariance matrix \(\Sigma_k\). The determinant \(\vert \Sigma_k \vert\) and the inverse \(\Sigma_k^{-1}\) are crucial components for computing probabilities.

Estimating the parameters for each class becomes computationally challenging in high dimensions, as the covariance matrix has \(O(d^2)\) parameters. This complexity often necessitates simplifying assumptions to make the model tractable.

How do we arrive at this complexity, and why is it considered computationally challenging?

In the Gaussian Bayes Classifier, each class \(k\) has its own covariance matrix \(\Sigma_k\), which is a \(d \times d\) matrix where \(d\) is the dimensionality of the feature space. For a single class, this covariance matrix has \(\frac{d(d+1)}{2}\) unique parameters. This is because a covariance matrix is symmetric, meaning that the upper and lower triangular portions are mirrors of each other. Specifically, the diagonal elements represent the variances, while the off-diagonal elements represent the covariances between different features.

For \(K\) classes, the total number of parameters required to estimate all the covariance matrices would be: \(K \times \frac{d(d+1)}{2}\)

This can become computationally expensive, especially when \(d\) (the number of features) is large.

This large number of parameters is the reason why the Gaussian Bayes Classifier faces challenges in high-dimensional settings, as the model needs to estimate these parameters from data, and estimating a large number of parameters requires a substantial amount of data. Moreover, when the dimensionality \(d\) is large relative to the number of training samples, the covariance matrix can become ill-conditioned or singular, which might lead to poor performance.

To handle this, simplifications such as assuming diagonal covariance matrices (where off-diagonal covariances are set to zero) or sharing a common covariance matrix across all classes are often made, which reduces the number of parameters that need to be estimated.

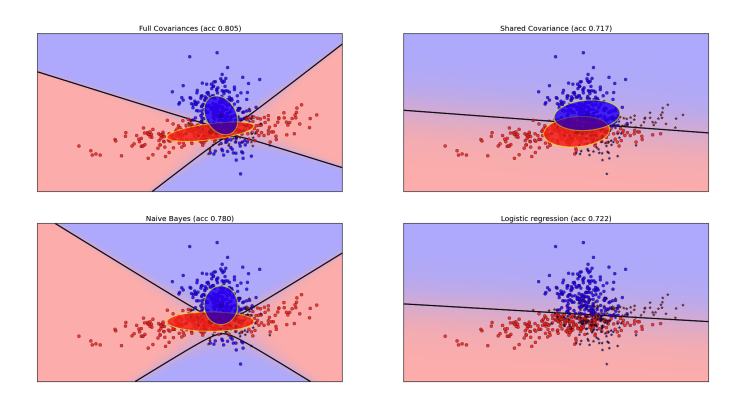

Special Cases of Gaussian Bayes Classifier

To address the computational challenges, we consider the following special cases of the Gaussian Bayes Classifier:

-

Full Covariance Matrix

Each class has its own covariance matrix \(\Sigma_k\). This allows for flexible modeling of the class distributions, as it can capture correlations between different features. The decision boundary, however, is quadratic, as the posterior probability depends on the quadratic term involving \((x - \mu_k)^\top \Sigma_k^{-1} (x - \mu_k)\).Decision Boundary Derivation:

\[\frac{p(x \vert t = k)}{p(x \vert t = l)} > 1\]

The decision rule is based on the ratio of the posterior probabilities:which leads to a quadratic expression involving the covariance matrices \(\Sigma_k\) and \(\Sigma_l\). This quadratic form creates a curved decision boundary.

Insight:

Since each class can have a different covariance matrix, the decision boundary can bend and adapt to the data’s true distribution, allowing for accurate classification even in complex scenarios. However, the computational cost is high because each class requires estimating a full covariance matrix with \(O(d^2)\) parameters. -

Shared Covariance Matrix

If all classes share a common covariance matrix \(\Sigma\), the decision boundary becomes linear. This assumption simplifies the model by treating all classes as having the same spread, reducing the number of parameters to estimate.Decision Boundary Derivation:

\[p(x \vert t = k) = \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{d/2} |\Sigma|^{1/2}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2}(x - \mu_k)^\top \Sigma^{-1} (x - \mu_k)\right)\]

In this case, the likelihood for each class is given by:The decision rule between two classes \(k\) and \(l\) simplifies to:

\[(x - \mu_k)^\top \Sigma^{-1} (x - \mu_k) - (x - \mu_l)^\top \Sigma^{-1} (x - \mu_l) = \text{constant}\]which is linear in \(x\). This results in a linear decision boundary between the classes.

Insight:

By assuming a common covariance matrix, we treat the class distributions as having the same shape and orientation. This simplifies the model and makes the decision boundary linear, leading to reduced computational cost and faster training. However, this may be less flexible if the true distributions of the classes are significantly different. -

Naive Bayes Assumption

The Naive Bayes classifier assumes that the features are conditionally independent given the class, meaning that the covariance matrix is diagonal. This leads to a model where each feature is treated independently when making class predictions.Decision Boundary Derivation:

\[p(x \vert t = k) = \prod_{i=1}^{d} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma_{k,i}^2}} \exp\left(-\frac{(x_i - \mu_{k,i})^2}{2\sigma_{k,i}^2}\right)\]

Under the Naive Bayes assumption, the covariance matrix is diagonal, so the likelihood for each class becomes:The decision rule between two classes \(k\) and \(l\) leads to a quadratic expression for each feature, but since the features are independent, the decision boundary remains quadratic overall, as the product of exponentials leads to terms that depend on the squares of the feature values.

Insight:

Even though the features are assumed to be independent, the decision boundary remains quadratic because of the feature-wise variances. The strong independence assumption makes the model computationally efficient, as it reduces the number of parameters to estimate (each class only requires \(d\) variances), but it limits the model’s flexibility to capture interactions between features.

Gaussian Bayes Classifier vs. Logistic Regression

One interesting connection between GBC and logistic regression arises when the data is truly Gaussian. If we assume shared covariance matrices, the decision boundaries produced by GBC become identical to those of logistic regression. However, logistic regression is more versatile since it does not rely on Gaussian assumptions and can learn other types of decision boundaries.

Note: Even though both methods produce the same linear decision boundary under the Gaussian assumption with shared covariance, the actual parameter values (weights and means) will be different because they are derived from different models and assumptions.

Final Thoughts

The multivariate Gaussian distribution provides a probabilistic framework for understanding data with correlated features. By extending this to classification tasks, the Gaussian Bayes Classifier offers an elegant and interpretable approach to modeling. However, its reliance on assumptions like Gaussianity and the complexity of covariance estimation in high dimensions present practical challenges.

Generative models, like GBC, aim to model the joint distribution \(p(x, y)\), which contrasts with discriminative models, such as logistic regression, that focus directly on \(p(y \vert x)\). While generative models offer a principled way to derive loss functions via maximum likelihood, they can struggle with small datasets, where estimating the joint distribution becomes difficult. Why?

Generative models typically use the product of the likelihood and the prior. Specifically, the likelihood \(p(x \mid y)\), can become challenging with small datasets because:

- Insufficient data for accurate parameter estimation: With limited data, the model may not have enough examples to accurately estimate the parameters of the distribution (such as the means and variances in the case of Gaussian distributions).

- Overfitting risk: With small datasets, the model may overfit to noise or specific patterns that don’t generalize well, leading to poor estimates of the joint distribution.

In contrast, discriminative models like logistic regression focus directly on \(p(y \mid x)\) and are less affected by small sample sizes because they only need to model the decision boundary between classes, making them more robust in such situations.

As you delve deeper into probabilistic frameworks, a question worth pondering is: Do generative models have an equivalent form of regularization to mitigate overfitting? This opens up avenues for exploring how these models can be made more robust in practice.

To address this question, we’ll next explore Bayesian Inference, where generative models can incorporate priors over their parameters. For instance, in a Gaussian Bayes Classifier, instead of relying on point estimates for means and variances, Bayesian methods treat these parameters as distributions. This approach naturally regularizes the model by spreading probability mass over plausible parameter values, reducing the risk of overfitting. Stay tuned—we’ll dive into this in the next post!