Gaussian Naive Bayes - A Natural Extension

In the previous blog, we explored the Naive Bayes (NB) model for binary features and how it works under the assumption of conditional independence. However, real-world datasets often include continuous features. How can we extend the NB framework to handle such cases? Let’s dive into Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB), a variant of NB that uses Gaussian distributions to model continuous inputs.

Before we start: I know this might be challenging to follow just by reading through, especially for this part. So, grab a pen and paper and work through it yourself. You’ll notice that within the summations, all terms except the one you’re differentiating with respect to are constants and will drop out (i.e., become zero). As you write it out, you’ll also understand why certain steps involve a change in sign. Working through it once will make everything much clearer and easier to grasp.

Consider a multiclass classification problem where each input feature \(x_i\) is continuous. To model \(p(x_i \mid y)\), we assume that the feature values follow a Gaussian (normal) distribution:

\[p(x_i \mid y = k) \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_{i,k}, \sigma^2_{i,k}),\]where \(\mu_{i,k}\) and \(\sigma^2_{i,k}\) are the mean and variance of \(x_i\) for class \(y = k\), respectively. Additionally, we model the class prior probabilities as:

\[p(y = k) = \theta_k.\]With these assumptions, the likelihood of the dataset becomes:

\[p(D) = \prod_{n=1}^N p_\theta(x^{(n)}, y^{(n)})\] \[p(D) = \prod_{n=1}^N p(y^{(n)}) \prod_{i=1}^d p(x_i^{(n)} \mid y^{(n)}).\]Substituting the Gaussian distribution for \(p(x_i \mid y)\), we get:

\[p(D) = \prod_{n=1}^N \theta_{y^{(n)}} \prod_{i=1}^d \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma_{i,y^{(n)}}^2}} \exp\left(-\frac{\left(x_i^{(n)} - \mu_{i,y^{(n)}}\right)^2}{2\sigma_{i,y^{(n)}}^2}\right).\]It may seem complex at first, but if you look closely, you’ll see that we’re applying the same principle. The only difference is in the distribution. To visualize this, we’ve essentially applied the distribution to a familiar form \((1)\) once again to obtain the result. Take a moment to reflect on this.

\[\hat{y} = \arg\max_{y \in \mathcal{Y}} p(x, y; \theta) = \arg\max_{y} p(y \mid x; \theta) = \arg\max_{y} p(x \mid y; \theta) p(y; \theta) \tag{1}\]Learning Parameters with Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE)

To train the Gaussian Naive Bayes model, we estimate the parameters \(\mu_{i,k}\), \(\sigma^2_{i,k}\), and \(\theta_k\) using MLE.

Mean (\(\mu_{i,k}\)):

The log-likelihood of the data is:

\[\ell = \sum_{n=1}^N \log \theta_{y^{(n)}} + \sum_{n=1}^N \sum_{i=1}^d \left[-\frac{1}{2} \log (2\pi \sigma_{i,y^{(n)}}^2) - \frac{\left(x_i^{(n)} - \mu_{i,y^{(n)}}\right)^2}{2\sigma_{i,y^{(n)}}^2}\right]\]Taking the derivative with respect to \(\mu_{j,k}\) and setting it to zero gives:

\[\mu_{j,k} = \frac{\sum_{n:y^{(n)}=k} x_j^{(n)}}{\sum_{n:y^{(n)}=k} 1}\]This is simply the sample mean of \(x_j\) for class \(k\).

Derivation of \(\mu_{j,k}\) for Gaussian Naive Bayes

To estimate the parameter \(\mu_{j,k}\), the mean of feature \(x_j\) for class \(k\), we maximize the log-likelihood with respect to \(\mu_{j,k}\).

Step 1: Compute the Derivative of the Log-Likelihood

The log-likelihood is differentiated with respect to \(\mu_{j,k}\):

\[\frac{\partial}{\partial \mu_{j,k}} \ell = \frac{\partial}{\partial \mu_{j,k}} \sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} \left( -\frac{1}{2 \sigma_{j,k}^2} \left( x_j^{(n)} - \mu_{j,k} \right)^2 \right)\]Ignoring irrelevant terms (constants that do not depend on \(\mu_{j,k}\)), this simplifies to:

\[\frac{\partial}{\partial \mu_{j,k}} \ell = \sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} \frac{1}{\sigma_{j,k}^2} \left( x_j^{(n)} - \mu_{j,k} \right)\]Step 2: Set the Derivative to Zero

To find the maximum likelihood estimate, set the derivative to zero:

\[\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} \frac{1}{\sigma_{j,k}^2} \left( x_j^{(n)} - \mu_{j,k} \right) = 0\]Step 3: Solve for \(\mu_{j,k}\)

Rearranging terms:

\[\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} x_j^{(n)} = \mu_{j,k} \sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} 1\]Divide both sides by \(\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} 1\):

\[\mu_{j,k} = \frac{\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} x_j^{(n)}}{\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} 1}\]Final Expression

The maximum likelihood estimate of \(\mu_{j,k}\) is:

\[\mu_{j,k} = \frac{\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} x_j^{(n)}}{\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} 1}\]Interpretation:

- \(\mu_{j,k}\) is the sample mean of \(x_j\) for all data points in class \(k\).

- This parameter is essential for defining the Gaussian distribution for feature \(x_j\) given class \(k\) in Gaussian Naive Bayes.

Variance (\(\sigma^2_{i,k}\)):

Similarly, the variance for feature \(x_j\) in class \(k\) is:

\[\sigma^2_{j,k} = \frac{\sum_{n:y^{(n)}=k} \left(x_j^{(n)} - \mu_{j,k}\right)^2}{\sum_{n:y^{(n)}=k} 1}\]Class Prior (\(\theta_k\)):

The class prior \(\theta_k\) is estimated as the proportion of data points belonging to class \(k\):

\[\theta_k = \frac{\sum_{n:y^{(n)}=k} 1}{N}\]Derivation of \(\sigma_{j,k}^2\) (Sample Variance) and \(\theta_k\) (Class Prior)

1. Derivation of \(\sigma_{j,k}^2\) (Sample Variance)

To derive the sample variance \(\sigma_{j,k}^2\), we start from the log-likelihood of the Gaussian distribution for feature \(x_j\) within class \(k\):

\[\ell = \sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} \left[ -\frac{1}{2} \log(2\pi \sigma_{j,k}^2) - \frac{\left( x_j^{(n)} - \mu_{j,k} \right)^2}{2\sigma_{j,k}^2} \right]\]We take the derivative of \(\ell\) with respect to \(\sigma_{j,k}^2\) and set it to zero:

\[\frac{\partial \ell}{\partial \sigma_{j,k}^2} = \sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} \left[ -\frac{1}{2\sigma_{j,k}^2} + \frac{\left( x_j^{(n)} - \mu_{j,k} \right)^2}{2\sigma_{j,k}^4} \right] = 0\]Simplify the equation:

\[\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} \left[ -\sigma_{j,k}^2 + \left( x_j^{(n)} - \mu_{j,k} \right)^2 \right] = 0\]Divide by \(\sigma_{j,k}^2\) and rearrange:

\[\sigma_{j,k}^2 = \frac{\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} \left( x_j^{(n)} - \mu_{j,k} \right)^2}{\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} 1}\]Thus, the MLE for \(\sigma_{j,k}^2\) is:

\[\sigma_{j,k}^2 = \frac{\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} \left( x_j^{(n)} - \mu_{j,k} \right)^2}{\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} 1}\]2. Derivation of \(\theta_k\) (Class Prior)

The class prior \(\theta_k\) represents the proportion of data points belonging to class \(k\) in the dataset. It is given by:

\[\theta_k = \frac{\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} 1}{N}\]Steps:

- Numerator: \(\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} 1\) counts the total number of data points that belong to class \(k\).

- Denominator: \(N\) is the total number of data points in the entire dataset.

Finally,

-

Sample Variance:

\[\sigma_{j,k}^2 = \frac{\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} \left( x_j^{(n)} - \mu_{j,k} \right)^2}{\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} 1}\] -

Class Prior:

\[\theta_k = \frac{\sum_{n: y^{(n)} = k} 1}{N}\]

- The sample variance \(\sigma_{j,k}^2\) measures the spread of feature \(x_j\) for class \(k\), derived using MLE.

- The class prior \(\theta_k\) represents the proportion of data points in class \(k\), computed directly from the dataset.

Decision Boundary of the Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB) Model

General Formulation of the Decision Boundary:

For binary classification (\(y \in \{0, 1\}\)), the log odds ratio is expressed as:

\[\log \frac{p(y=1 \mid x)}{p(y=0 \mid x)} = \log \frac{p(x \mid y=1)p(y=1)}{p(x \mid y=0)p(y=0)}.\]If you’re unclear about what the log odds ratio is, it represents the logarithm of the ratio of the probabilities of the two classes. By setting the log odds ratio to zero, we identify the points where the model is equally likely to classify a sample as belonging to either class.

In Gaussian Naive Bayes, this involves substituting the Gaussian distributions for \(p(x \mid y)\), simplifying the expression, and determining whether the resulting decision boundary is quadratic or linear based on the assumptions about the variances.

Thus, the log odds ratio serves as a straightforward mathematical tool to derive the decision boundary by locating the regions where the probabilities of the two classes are equal.

So, the conditional distributions \(p(x_i \mid y)\) are Gaussian:

\[p(x_i \mid y) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma_{i,y}^2}} \exp\left(-\frac{(x_i - \mu_{i,y})^2}{2\sigma_{i,y}^2}\right).\]Substituting this into the log odds equation, we get:

\[\log \frac{p(y=1 \mid x)}{p(y=0 \mid x)} = \log \frac{\theta_1}{\theta_0} + \sum_{i=1}^d \left[\log \sqrt{\frac{\sigma_{i,0}^2}{\sigma_{i,1}^2}} + \frac{(x_i - \mu_{i,0})^2}{2\sigma_{i,0}^2} - \frac{(x_i - \mu_{i,1})^2}{2\sigma_{i,1}^2}\right].\]This equation represents the general case of the GNB decision boundary.

Linear vs. Quadratic Decision Boundaries

Quadratic Decision Boundary:

In the general case, where the variances \(\sigma_{i,0}^2\) and \(\sigma_{i,1}^2\) differ between classes, the decision boundary is quadratic. This is due to the presence of quadratic terms in the numerator:

\[\frac{(x_i - \mu_{i,0})^2}{2\sigma_{i,0}^2} - \frac{(x_i - \mu_{i,1})^2}{2\sigma_{i,1}^2}.\]Linear Decision Boundary:

When we assume the variances are equal for both classes \((\sigma_{i,0}^2 = \sigma_{i,1}^2 = \sigma_i^2)\), the quadratic terms cancel out. Simplifying the log odds equation yields:

\[\log \frac{p(y=1 \mid x)}{p(y=0 \mid x)} = \sum_{i=1}^d \frac{\mu_{i,1} - \mu_{i,0}}{\sigma_i^2} x_i + \sum_{i=1}^d \frac{\mu_{i,0}^2 - \mu_{i,1}^2}{2\sigma_i^2}.\]In matrix form, this becomes:

\[\log \frac{p(y=1 \mid x)}{p(y=0 \mid x)} = \theta^\top x + \theta_0,\]where:

- \[\theta_i = \frac{\mu_{i,1} - \mu_{i,0}}{\sigma_i^2}, \quad i \in [1, d]\]

- \[\theta_0 = \sum_{i=1}^d \frac{\mu_{i,0}^2 - \mu_{i,1}^2}{2\sigma_i^2}.\]

Thus, under the shared variance assumption, the decision boundary is linear.

Takeaways:

- Quadratic Boundary: The difference in variances between the two classes introduces curvature, resulting in a nonlinear boundary.

- Linear Boundary: Equal variances lead to a linear boundary, making the model behave similarly to logistic regression.

This derivation connects Gaussian Naive Bayes to logistic regression and helps to understand its behavior under different assumptions.

Naive Bayes vs. Logistic Regression

Both Naive Bayes and logistic regression are popular classifiers, but they differ fundamentally in their approach:

| Logistic Regression | Gaussian Naive Bayes | |

|---|---|---|

| Model Type | Conditional/Discriminative | Generative |

| Parametrization | \(p(y \mid x)\) | \(p(x \mid y), p(y)\) |

| Assumptions on Y | Bernoulli | Bernoulli |

| Assumptions on X | — | Gaussian |

| Decision Boundary | \(\theta_{LR}^\top x\) | \(\theta_{GNB}^\top x\) |

-

Logistic Regression (LR) is a discriminative model that directly models the conditional probability \(p(y \mid x)\). It does not make assumptions about the distribution of features \(X\) but instead focuses on finding a decision boundary that separates the classes based on the observed data.

-

Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB), on the other hand, is a generative model that explicitly models the joint distribution \(p(x, y)\) by assuming that the features \(X\) are conditionally Gaussian given the class \(y\).

A few questions to address before we wrap up.

Question 1: Given the same training data, is \(\theta_{LR} = \theta_{GNB}\)?

- This is a critical question to explore the relationship between discriminative and generative models. While the forms of the decision boundary (e.g., linear) may look similar under certain assumptions (e.g., shared variance in GNB), the parameters \(\theta_{LR}\) and \(\theta_{GNB}\) are generally not the same due to differences in how the two models approach the learning process.

Question 2: Relationship Between LR and GNB

- Logistic regression and Gaussian naive Bayes converge to the same classifier asymptotically, assuming the GNB assumptions hold:

- Data points are generated from Gaussian distributions for each class.

- Each dimension of the feature vector is generated independently.

- Both classes share the same variance for each feature (shared variance assumption).

- Under these conditions, the decision boundary derived from GNB becomes identical to that of logistic regression as the amount of data increases.

Question 3: What Happens if the GNB Assumptions Are Not True?

- If the assumptions of GNB are violated (e.g., features are not Gaussian, dimensions are not independent, or variances are not shared), the decision boundary derived by GNB can deviate significantly from the optimal boundary. In such cases:

- Logistic Regression is likely to perform better, as it does not rely on specific assumptions about the feature distributions.

- GNB may produce suboptimal results because its assumptions are hardcoded into the model and do not adapt to the true data distribution.

Thus, the choice between LR and GNB depends heavily on whether the data aligns with GNB’s assumptions.

Generative vs. Discriminative Models: Trade-offs

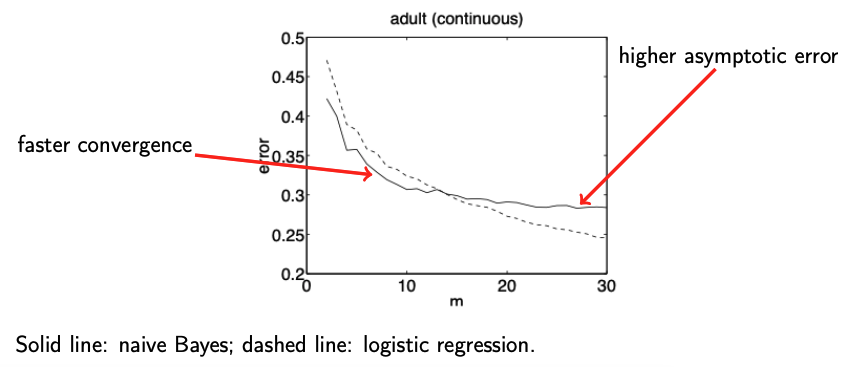

The contrast between Naive Bayes and logistic regression highlights the differences between generative and discriminative models. Generative models like Naive Bayes model the joint distribution \(p(x, y)\), allowing them to generate data as well as make predictions. In contrast, discriminative models like logistic regression focus directly on \(p(y \mid x)\), optimizing for classification accuracy.

This tradeoff is explored in the classic paper by Ng, A. and Jordan, M. (2002), On discriminative versus generative classifiers: A comparison of logistic regression and naive Bayes., which shows that generative models converge faster but may have higher asymptotic error compared to their discriminative counterparts.

In the next section, we’ll explore the Multivariate Gaussian Distribution and the Gaussian Bayes Classifier in greater detail. Stay tuned👋!