Conjugate Priors and Bayes Point Estimates

Bayesian statistics provides us with a framework to incorporate prior knowledge, update our beliefs with new evidence, and make principled decisions. Two key concepts in this framework are Bayes Point Estimates and Conjugate Priors, which we will explore in this blog post. These ideas not only simplify computations but also help us build intuition for Bayesian inference.

What are Conjugate Priors?

Imagine having a prior belief about the world, represented by a probability distribution. When new data arrives, Bayesian inference updates this belief, resulting in a posterior distribution. Now, if the updated posterior distribution belongs to the same family as the prior, we call the prior conjugate for the chosen likelihood model.

Formally, let \(\pi\) denote a family of prior distributions over the parameter space \(\Theta\), and let \(P\) represent a parametric likelihood model. We say that the family \(\pi\) is conjugate to \(P\) if, for any prior in \(\pi\), the posterior distribution also belongs to \(\pi\).

A classic example of conjugate priors is the Beta distribution for the Bernoulli model (used to model coin flips). If the prior belief about a coin’s bias follows a Beta distribution, the posterior distribution after observing the coin flips will also follow a Beta distribution. This conjugacy greatly simplifies the mathematical computations in Bayesian updating.

A simple way to form an intuition about this is to think of conjugate priors as allowing the mathematical form of your beliefs (prior) and your updated beliefs (posterior) to stay consistent. It’s like using a “familiar language” for both your starting beliefs and your updated beliefs—making things easier to compute and interpret.

So, with this, you can see why we chose the beta distribution in the last blog, right? Great! Now, let’s continue with the same example to explore further.

A Concrete Example: Coin Flipping

Let’s make this more concrete by revisiting the example from the last blog. Suppose we have a coin that may be biased, and we want to estimate its bias \(\theta\) (the probability of landing heads).

Note: If the notation or its meaning is unclear, check out the previous blog for clarification.

The probability model for a single coin flip is given by:

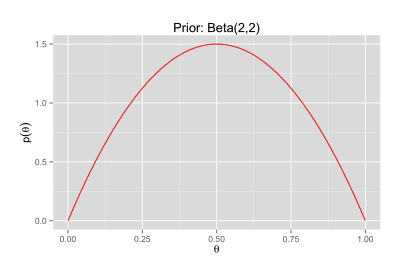

\[P(\text{Heads} \mid \theta) = \theta, \quad \theta \in [0,1]\]Before flipping the coin, we encode our prior belief about \(\theta\) using a Beta distribution: \(\theta \sim \text{Beta}(2, 2).\)

This Beta distribution reflects a prior belief that the coin is likely fair (centered around \(\theta = 0.5\)), but with some uncertainty.

Now, we flip the coin multiple times and observe the following data: \(D = \{\text{H, H, T, T, T, T, T, H, ..., T}\},\)

where the coin lands on heads 75 times and tails 60 times.

Updating Beliefs: The Posterior Distribution

Using Bayes’ theorem, we combine the prior and the likelihood of the observed data to compute the posterior distribution:

\[p(\theta \mid D) \propto p(D \mid \theta) p(\theta)\]For the Beta-Bernoulli model, the posterior distribution is also Beta-distributed, with updated parameters:

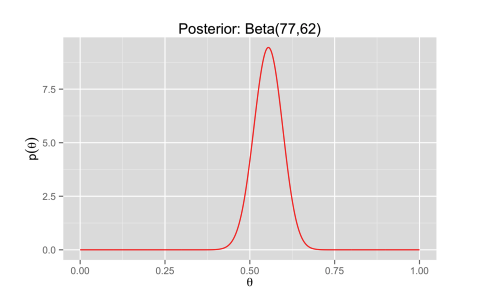

\[\theta \mid D \sim \text{Beta}(\alpha + \text{Heads}, \beta + \text{Tails})\]In our example, the prior parameters are \(\alpha = 2\) and \(\beta = 2\). After observing 75 heads and 60 tails, the posterior becomes:

\[\theta \mid D \sim \text{Beta}(2 + 75, 2 + 60) = \text{Beta}(77, 62)\]This posterior distribution captures our updated belief about the coin’s bias after incorporating the observed data.

Takeaway: The Beta distribution’s conjugacy with the Bernoulli likelihood model makes updating beliefs straightforward. The posterior parameters are simply the sum of the prior parameters and the counts of heads and tails, which means Bayesian updating is computationally efficient and intuitive in this case.

Bayesian Point Estimates

Once we have the posterior distribution, the next question is: how do we summarize it into a single value? This is where Bayes Point Estimates come into play. These estimates provide a representative value for \(\theta\) based on the posterior.

One common approach is the posterior mean, which represents the expected value of \(\theta\) under the posterior distribution:

\[\hat{\theta}_{\text{mean}} = \mathbb{E}[\theta \mid D] = \frac{\alpha + \text{Heads}}{\alpha + \beta + \text{Heads} + \text{Tails}}\]Substituting the parameters from our example:

\[\hat{\theta}_{\text{mean}} = \frac{77}{77 + 62} \approx 0.554\]Another popular estimate is the Maximum a Posteriori (MAP) estimate, which is the mode of the posterior distribution. For the Beta distribution, the MAP estimate is given by:

\[\hat{\theta}_{\text{MAP}} = \frac{\alpha - 1}{\alpha + \beta - 2}, \quad \text{if } \alpha > 1 \text{ and } \beta > 1\]Alternatively, the MAP estimate can be expressed as:

\[\hat{\theta}_{\text{MAP}} = \arg\max_\theta p(\theta \mid D)\]Using our parameters:

\[\hat{\theta}_{\text{MAP}} = \frac{77 - 1}{77 + 62 - 2} = \frac{76}{137} \approx 0.555\]Both the posterior mean and the MAP estimate provide valuable insights into the coin’s bias, with slight differences depending on how they summarize the posterior.

Posterior Mean vs. MAP Estimate

- Posterior Mean (Expected Value):

- Analogy: Think of the posterior mean like a “balanced average”. It provides a representative value for \(\theta\) by averaging all possible values, weighted by their likelihood under the posterior distribution. This is especially useful when you want an overall estimate that incorporates all the data.

- When to use: The posterior mean is often a good choice when the data is symmetric or you have a large sample size, and you need a balanced estimate.

- Example: The posterior mean gives us a fair estimate of the coin’s bias, accounting for both the prior belief and the observed data.

- Maximum a Posteriori (MAP) Estimate (Mode):

- Analogy: The MAP estimate is like finding the “peak” of a hill. It’s the value of \(\theta\) where the posterior distribution is most concentrated. This is useful when you care about the most probable value of \(\theta\) based on both the data and the prior.

- When to use: The MAP estimate is helpful when you have a strong prior or sparse data. It gives you the point estimate where the posterior distribution is maximized.

- Example: The MAP estimate gives us the most likely value of the coin’s bias after considering both the data and prior belief.

So, The posterior mean gives a more general, balanced estimate, while the MAP estimate is more focused on the most likely value based on your prior and data. The choice between the two depends on your data, the role of your prior, and what you want to emphasize in your estimate.

Beyond Point Estimates: What Else Can We Do with the Posterior?

The posterior distribution is far more than just a tool for calculating point estimates. It encapsulates the full range of uncertainty about \(\theta\) and opens up a variety of analytical possibilities. Here are a few ways we can make use of the posterior:

Visualize Uncertainty

- Means: One of the most powerful features of the posterior distribution is its ability to represent uncertainty. By plotting the posterior, we can visually assess how concentrated or spread out our beliefs about \(\theta\) are.

- Mental Image: Imagine you’re standing at the top of a mountain, looking at a wide valley. The posterior distribution is like the shape of the valley, and the height of the valley at each point shows how likely that value of \(\theta\) is. A tall peak indicates a strong belief in that value, while a flatter, broader area indicates more uncertainty.

- When to Use: Visualizing uncertainty helps you understand not just where the most likely value lies, but also how uncertain we are about that estimate. A wide, flat posterior suggests we’re less confident about \(\theta\), while a narrow, tall one suggests we’re very confident.

Construct Credible Intervals

- Means: A credible interval is the Bayesian equivalent of a confidence interval.

- Mental Image: Think of a credible interval as a fence that you build around the values of \(\theta\) that you believe are most likely. If you set a 95% credible interval, the fence will surround the areas where there’s a 95% chance that \(\theta\) falls within, based on the data.

- When to Use: Credible intervals are great when you want a range of plausible values. It’s like saying, “We’re 95% confident that \(\theta\) lies somewhere in this range.” The fence keeps out the outliers and shows you where the most likely values lie.

Make Decisions Using Loss Functions

- Means: Bayesian decision theory provides a framework for making decisions based on the posterior distribution, incorporating a specific loss function.

- Mental Image: Imagine you’re a chess player deciding on the best move based on the board’s current state. The loss function is like your strategy guide, telling you which move will minimize your risk or maximize your reward. In the case of Bayesian decision theory, the posterior distribution is your chessboard, and the loss function guides you to the best move.

- For mean-squared error, it’s like choosing the move that optimizes your position across the entire game (this corresponds to the posterior mean).

- For 0-1 loss, you’re making a more focused decision, like trying to choose the most immediate or most probable move (this corresponds to the MAP estimate).

- When to Use: Loss functions help you make decisions based on the costs or benefits of various choices. If you’re optimizing for accuracy and minimizing error, go with the posterior mean. If you’re trying to maximize the most likely outcome, go with the MAP.

These tools allow for flexible, data-driven decision-making, enabling us to quantify uncertainty and select the best possible estimate of \(\theta\) based on our specific objectives.

Conclusion

In this post, we explored the concepts of conjugate priors and Bayesian point estimates through the lens of a coin-flipping example. Conjugate priors simplify Bayesian updating by keeping the posterior distribution within the same family as the prior. Meanwhile, point estimates and posterior analysis allow us to extract actionable insights and communicate uncertainty effectively.

By mastering these foundational concepts, we’re now equipped to apply Bayesian inference to a variety of real-world problems. But, if you feel like you’re still struggling to link all the pieces together and form a high-level view of what’s happening, you’re not alone—I felt the same way too. So, next, we’ll dive into Bayesian decision theory and see how all these concepts connect, helping us make predictions for our ML problems at hand. Stay tuned!