Apache Kafka

Data at rest versus data in motion

- So far in this semester, we have been focusing on data at rest.

- The data is stored in a storage system.

- Examples: HDFS, Hive, HBase, …

- Today, we will focus on data in motion.

- The data is in route between source and destination in the network.

- We need to handle the continuous flow of data.

Why is it important?

- We need to get the data from where it is created to where it can be analyzed.

- The faster we can do this, the more agile and responsive our business can be.

- The less effort we spend on moving data around, the more we can focus on the core business at hand.

- This is why the pipeline is a critical component in the data-driven business.

- How we move the data becomes nearly as important as the data itself.

A critical component of data-driven applications

- Publish/subscribe (pub/sub) messaging is a pattern that is characterized by the sender (publisher) of a piece of data (message) not specifically directing it to a receiver.

- Instead, the publisher classifies the message somehow, and that receiver (subscriber) subscribes to receive certain classes of messages.

- Publish/subscribe systems often have a broker, a central point where messages are published, to facilitate this pattern.

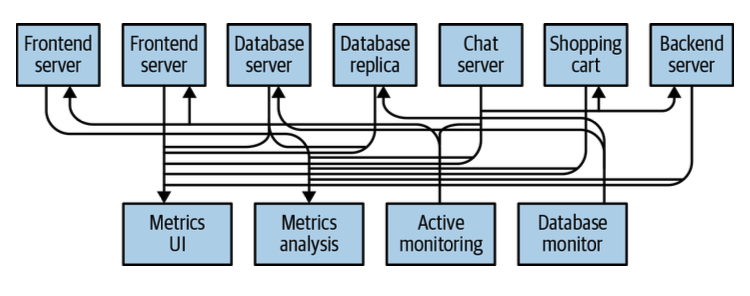

How it starts

- Many use cases for publish/subscribe start out the same way: with a simple message queue or interprocess communication channel.

- Example: Suppose you create an application that needs to send monitoring information somewhere…

- You open a direct connection from your application to an application that displays your metrics on a dashboard.

- Then, you push metrics over that connection.

- As you have more applications that are using those servers to get individual metrics and use them for various purposes, your architecture soon becomes…

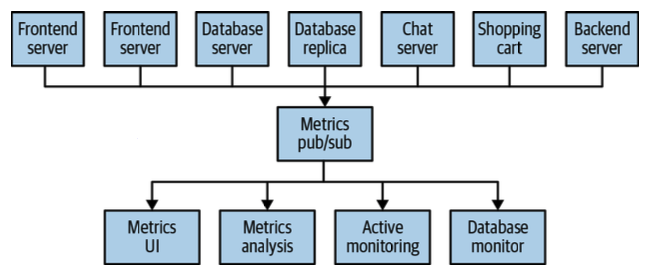

- To clean up that mess, you set up a single application that receives metrics from all the applications out there, and provide a server to query those metrics for any system that needs them.

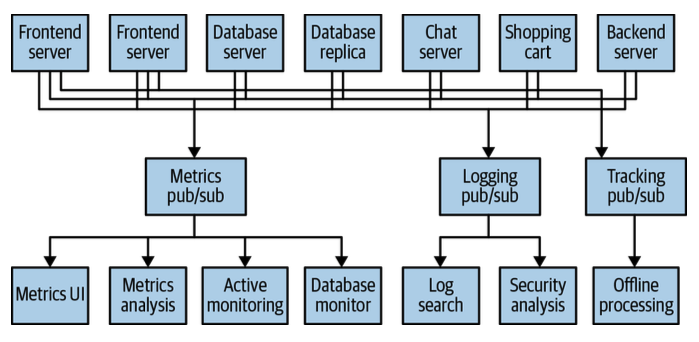

- Maybe you need to process more than metrics data…

- There is still a lot of duplication in the system!

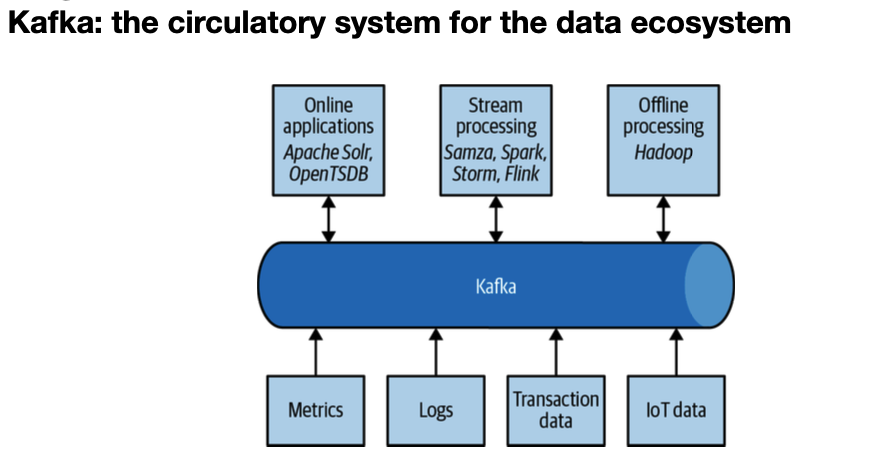

- What you would like to have is a single centralized system that allows for publishing generic types of data, which will grow as your business grows. Kafka to the rescue!

Kafka basics

Overview

- Kafka was developed as a publish/subscribe messaging system designed to solve this problem.

- It is often described as a distributing streaming platform.

- Data within Kafka is stored durably, in order, and can be read deterministically.

- In addition, the data can be distributed within the system to provide additional protections against failures, as well as significant opportunities for scaling performance.

- Q: What does “distributed streaming platform” mean in Kafka?

- A: A distributed streaming platform is a system that can collect, store, process, and deliver continuous streams of data across multiple machines. In Kafka’s case, “streaming” means data is produced and consumed continuously (not as one-time batches), and “distributed” means the data and workload are spread across many brokers for scalability and fault tolerance. Kafka keeps streams durably on disk, ordered within partitions, and replicated so that failures of individual machines do not cause data loss, while allowing many producers and consumers to operate in parallel.

Messages

- The unit of data within Kafka is called a message. It’s similar to a row or a record in a database.

- A message is simply an array of bytes. The data contained within it does not have a specific format or meaning to Kafka.

- A message can have an optional piece of metadata, referred to as a key.

- The key is also a byte array and also has no specific meaning to Kafka.

- Keys are used when messages are to be written to partitions in a more controlled manner.

- Q: What does it mean that a message is an “array of bytes”?

- A: When Kafka says a message (and its key) is an array of bytes, it means Kafka treats message data as raw binary data (byte[]) without interpreting its structure or semantics. Kafka does not care whether those bytes represent a string, JSON, Avro, Protobuf, an image, or anything else. It simply stores and transfers bytes efficiently. It is the responsibility of producers to serialize objects into bytes and consumers to deserialize those bytes back into meaningful data using an agreed-upon format.

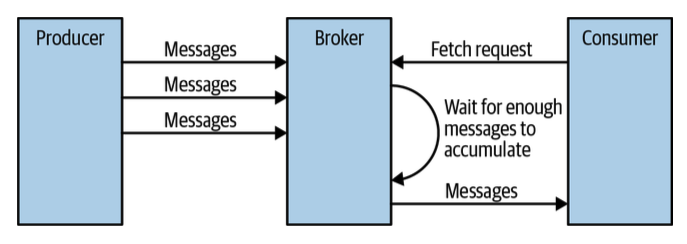

Batches

- For efficiency, messages are written into Kafka in batches.

- A batch is just a collection of messages, all of which are being produced to the same topic and partition.

- This is a trade-off between latency and throughput. The larger the batches, the more messages that can be handled per unit of time, but the longer it takes an individual message to propagate.

- Batches are typically compressed, providing more efficient data transfer and storage at the cost of some processing power.

Schemas

- Although Kafka itself treats messages as opaque byte arrays, in practice applications need a schema to describe the structure and meaning of the data inside those bytes. A schema defines fields, data types, and sometimes rules, making messages easier to interpret, validate, and evolve over time. Without schemas, producers and consumers must rely on implicit agreements, which easily break as systems change.

- Formats like JSON or XML are popular because they are simple and human readable, but they lack strong typing and make it hard to safely evolve data formats without breaking consumers. Apache Avro, on the other hand, provides compact binary serialization, strict data types, and built-in support for schema evolution. Avro keeps schemas separate from the message payload and does not require regenerating code when schemas change, which fits well with Kafka’s long-lived data streams.

- A consistent schema allows producers and consumers to evolve independently. If schemas are versioned and stored in a shared repository (such as a Schema Registry), producers can start writing data with a new schema version while consumers continue to read older versions or gradually adapt. This avoids tight coordination where all producers and consumers must be updated at the same time, enabling safer upgrades and more flexible, scalable Kafka-based systems.

- Conceptual Flow: In Kafka, the message itself is just a byte array (both the value and the optional key). Kafka does not understand or enforce any schema. The schema is used by the producer and consumer, not by Kafka, to serialize data into bytes when writing and deserialize bytes back into structured data when reading. Typically, the producer serializes an object according to a schema (for example, Avro) into a byte array and sends it to Kafka, and the consumer uses the same (or a compatible) schema to interpret those bytes. When a schema registry is used, the schema information is stored separately and referenced by the message, enabling versioning and compatibility without embedding the full schema in every message.

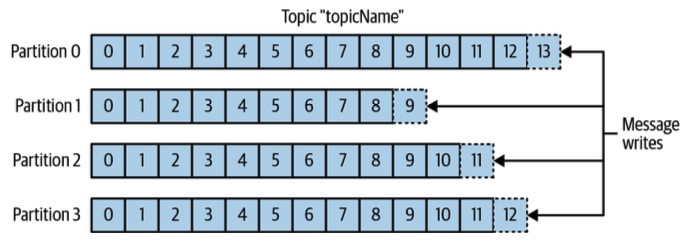

Topics and partitions

- Messages in Kafka are categorized into topics. They’re similar to tables in a database or folders in a filesystem.

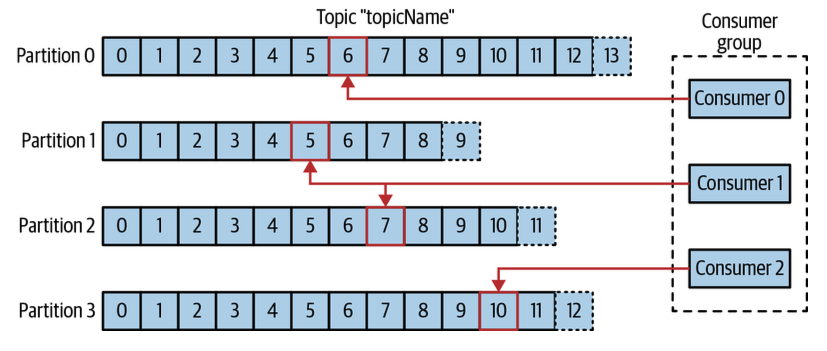

- Topics are additionally broken down into a number of partitions.

- Example: Suppose we use Kafka to store the commit log.

- Then, a partition would be a single log.

- Messages are written to it in an append-only fashion and are read in order from beginning to end.

- A topic typically has multiple partitions.

- Kafka guarantees message ordering within each partition, but there is no guarantee of message ordering across the entire topic.

- Partitions are the mechanism Kafka uses to achieve scalability and fault tolerance. Because each partition of a topic can be placed on a different broker (server), Kafka can spread the load of reads and writes across many machines, allowing a single topic to scale horizontally beyond the limits of one server. To handle failures, partitions can also be replicated, meaning the same partition is stored on multiple brokers; if one broker fails, another replica can take over without data loss.

- The term stream is a logical concept used when talking about how data flows through Kafka-based systems. A stream refers to all the data in a topic as a whole, even though that topic may be physically split across many partitions. From the perspective of producers and consumers, this represents a continuous flow of records over time.

- This terminology becomes especially important in stream processing, where frameworks (such as Kafka Streams, Flink, or Spark Streaming) process data as it arrives, rather than in batches. These frameworks treat a topic as a single stream of events, abstracting away the underlying partitions while still leveraging them internally for parallelism and scalability.

- More clearly: a Kafka topic is logically one stream of messages, but physically it is split into partitions. When replication is not used, each partition holds different messages, and together all partitions make up the complete data for the topic. No two partitions contain the same records. Messages are assigned to partitions (based on key or round-robin), and once written, they exist only in that one partition. Replication, when enabled, simply creates copies of a partition’s data on other brokers for fault tolerance; it does not change the fact that partitions themselves divide the topic’s data uniquely.

Producers and consumers

- In Kafka, clients are applications that interact with the Kafka cluster, and they come in two fundamental types: producers and consumers. A producer publishes (writes) messages to Kafka topics, while a consumer subscribes to topics and reads messages from them.

- On top of these basic clients, Kafka provides advanced client APIs. Kafka Connect is used for data integration, allowing Kafka to reliably move data between Kafka and external systems like databases, filesystems, or cloud services with minimal custom code. Kafka Streams is a stream-processing library that lets applications read from Kafka topics, process the data in real time (such as filtering, aggregating, or joining streams), and write the results back to Kafka.

- Internally, both Kafka Connect and Kafka Streams are built using producers and consumers, but they expose higher-level abstractions so developers can focus on integration or processing logic rather than low-level messaging details.

Producers

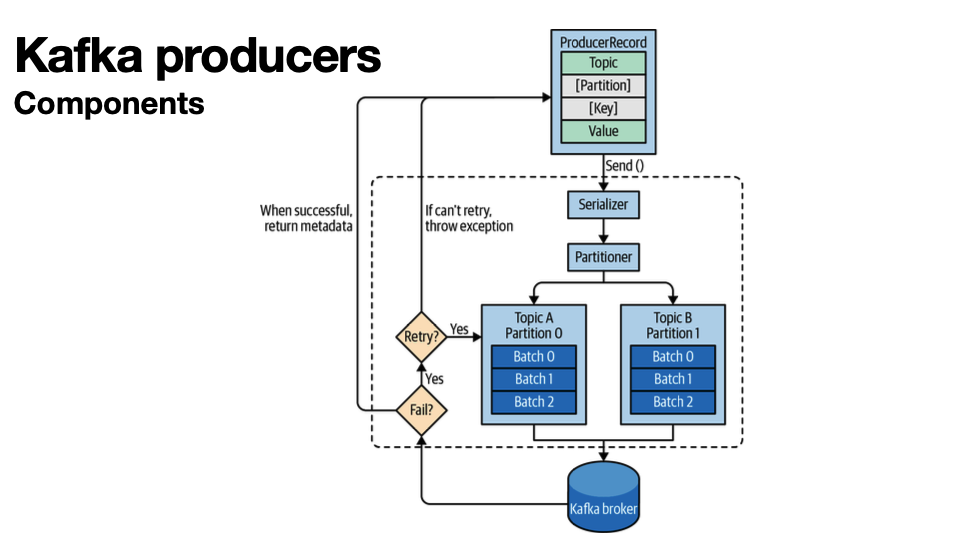

- Producers (a.k.a., publishers or writers) create new messages.

- A message will be produced to a specific topic.

- By default, the producer will balance messages over all partitions of a topic.

- In some cases, the producer will direct messages to specific partitions.

- This is typically done using the message key and a partitioner that will generate a hash of the key and map it to a specific partition. This ensures that all messages produced with the same key will get written to the same partition.

- The producer could also use a custom partitioner that follows other business rules for mapping messages to partitions.

Consumers

- Consumers (a.k.a., subscribers or readers) read messages.

- The consumer subscribes to one or more topics and reads the messages in the order in which they were produced to each partition.

- The consumer keeps track of which messages it has already consumed by keeping track of the offset of messages.

Offsets

- Kafka tracks a consumer’s progress using offsets, which are monotonically increasing integer values that Kafka assigns to messages as they are appended to a partition.

- Each message in a partition has a unique offset, and later messages always have larger offsets (though some numbers may be skipped).

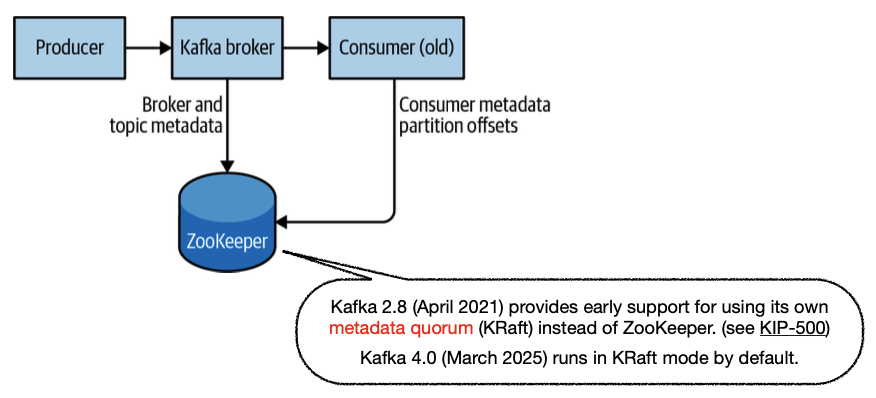

- A consumer records the next offset to read for each partition it consumes from; this offset is stored persistently (earlier in ZooKeeper, now typically in Kafka itself). Because offsets are stored outside the consumer process, a consumer can stop, crash, or restart and then resume reading from exactly where it left off, without losing or reordering data.

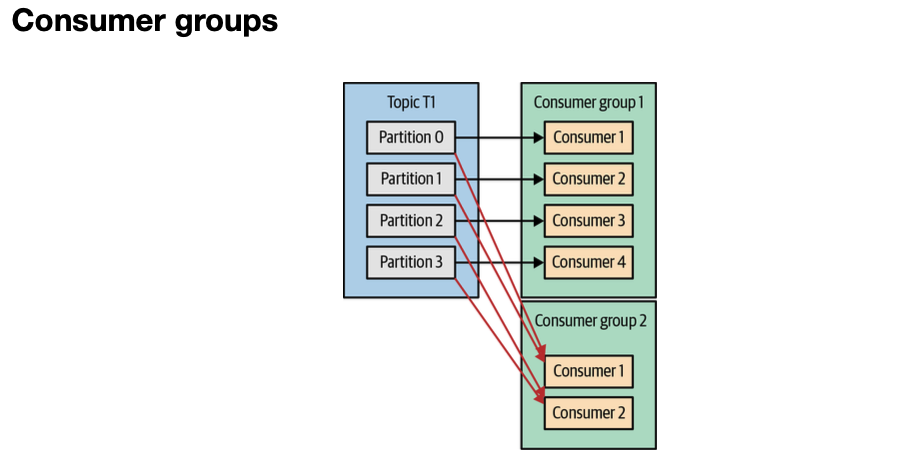

Consumer group

- Consumers work as part of a consumer group, which is one or more consumers that work together to consume a topic.

- The group ensures that each partition is only consumed by one member.

- The mapping of a consumer to a partition is often called ownership of the partition by the consumer.

- In this way, consumers can horizontally scale to consume topics with a large number of messages.

- If a single consumer fails, the remaining members of the group will reassign the partitions being consumed to take over for the missing member.

- Note:

- A consumer can consume from multiple partitions if there are fewer consumers than partitions.

- If there are more consumers than partitions, some consumers will be idle.

Brokers

- A single Kafka server is called a broker.

- The broker receives messages from producers, assigns offsets to them, and writes the messages to storage on disk.

- It also services consumers, responding to fetch requests for partitions and responding with the messages that have been published.

- A single broker can usually handle thousands of partitions and millions of messages per second.

Clusters

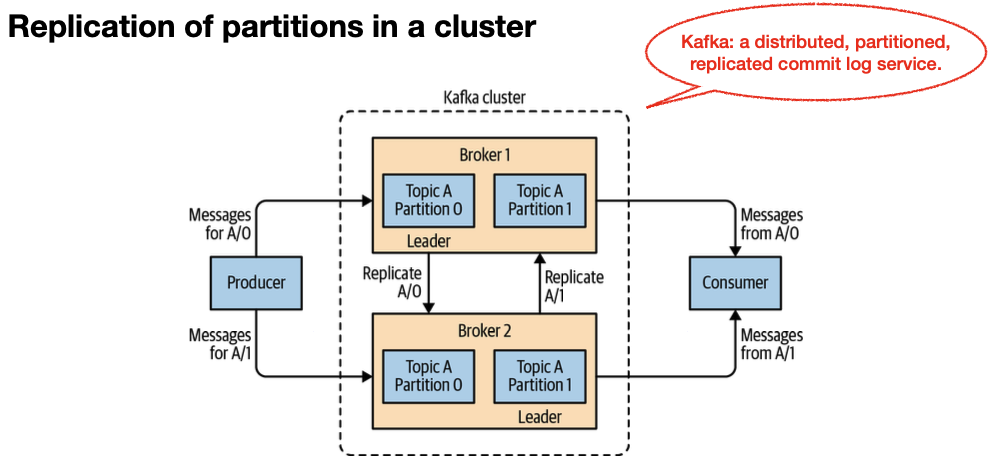

- Kafka brokers are designed to operate as part of a cluster.

- Within a cluster of brokers, one broker will also function as the cluster controller (automatically elected from the live members of the cluster).

- The controller is responsible for administrative operations, including assigning partitions to brokers and monitoring for broker failures.

Leader and followers

- A partition is owned by a single broker in the cluster. That broker is called the leader of the partition.

- A replicated partition is assigned to additional brokers. They are called followers of the partition.

- Replication provides redundancy of messages in the partition. If there is a broker failure, one of the followers can take over leadership.

- All producers must connect to the leader in order to publish messages, but consumers may fetch from either the leader or one of the followers.

Retention

- Retention is the durable storage of messages for some period of time.

- Kafka brokers are configured with a default retention setting for topics.

- Time-based retention: retaining messages for some period of time (e.g., 7 days)

- Space-based retention: retaining until the partition reaches a certain size in bytes (e.g., 1 GB).

- Once these limits are reached, messages are expired and deleted.

- Individual topics can also be configured with their own retention settings so that messages are stored for only as long as they are useful.

- Example

- A tracking topic might be retained for several days.

- Application metrics might be retained for only a few hours.

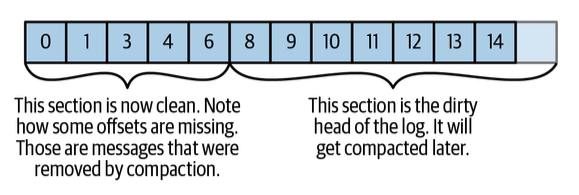

- Topics can also be configured as log compacted.

- Kafka will retain only the last message produced with a specific key.

- Useful for changelog data, where only the last update is interesting.

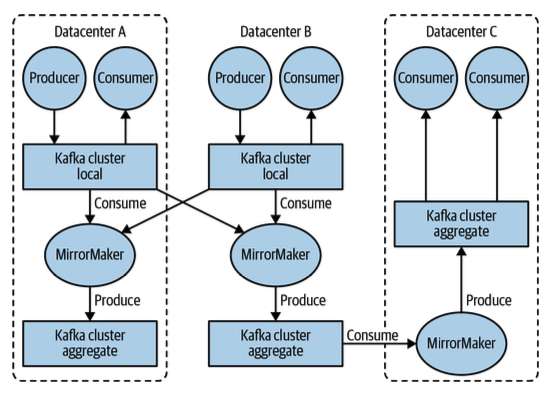

Multiple clusters

- As Kafka deployments grow, it also supports multiple clusters.

- Why is it useful?

- Segregation of types of data.

- Isolation for security requirements.

- Multiple data centers (disaster recovery).

- When working with multiple data centers in particular, it is often required that messages be copied between them. However, the replication mechanisms within the Kafka clusters are designed only to work within a single cluster, not between multiple clusters.

- MirrorMaker is a tool for replicating data to other clusters.

- At its core, MirrorMaker is simply a Kafka consumer and producer, linked together with a queue.

- Messages are consumed from one Kafka cluster and produced to another.

What makes Kafka a good choice?

- Multiple producers: Ideal for aggregating data from many frontend systems and making it consistent.

- Multiple consumers: Multiple consumers can read any single stream of messages without interfering with other clients.

- Disk-based retention: If a consumer falls behind or temporarily becomes offline, there is no danger of losing data.

- Scalable: Expansions can be performed while the cluster is online, without impacting whole system availability.

- High performance: Kafka provides sub-second message latency from producing a message to availability to consumers.

Note:

- If a topic has 2 partitions and 4 consumers in the same consumer group, Kafka assigns at most one consumer per partition, so only 2 consumers actively read data (one per partition) while the remaining 2 stay idle; adding more consumers does not increase throughput because parallelism is bounded by the number of partitions. If one of the active consumers fails, Kafka automatically triggers a rebalance and assigns the affected partition to one of the idle consumers, which then continues consuming from the last committed offset. If the 4 consumers belong to different consumer groups, each group independently consumes all messages from both partitions, meaning all 4 consumers receive the full data stream.

- Follow-up: What happens when partitions are replicated?

- When partitions are replicated, each partition has one leader replica and one or more follower replicas on different brokers. Consumers always read from the leader replica. If the broker hosting the leader fails, Kafka automatically elects one of the in-sync follower replicas as the new leader, and consumers continue reading transparently without data loss (assuming the replica was in sync). Replication therefore provides fault tolerance and high availability, but it does not increase consumer parallelism—only the number of partitions does.

Use cases

- Activity tracking

- The original use case for Kafka at LinkedIn is user activity tracking.

- A website’s users interact with frontend applications, which generate messages regarding actions the user is taking.

- Passive information: page views, click tracking, …

- More complex information: a user adds to their profile, …

- The messages are published to one or more topics, which are then consumed by applications on the backend. These applications generate reports, feed machine learning systems, update search results, or perform other operations to provide a rich user experience.

- Messaging

- Kafka is also used for messaging, where applications need to send notifications (e.g., emails) to users.

- Those applications can produce messages without needing to be concerned about formatting or how the messages will actually be sent.

- A single application can then read all the messages to be sent and handle them consistently, including:

- Formatting the messages (a.k.a., decorating) using a common look and feel.

- Collecting multiple messages into a single notification to be sent.

- Applying a user’s preferences for how they want to receive messages.

- Metrics and logging

- Kafka is also ideal for collecting application and system metrics and logs.

- Applications publish metrics on a regular basis to a Kafka topic, and those metrics can be consumed by systems for monitoring and alerting.

- They can also be used in an offline system (e.g., Hadoop) to perform longer-term analysis (e.g., growth projections), or routed to dedicated log search systems (e.g., Elasticsearch, security analysis applications).

- When the destination system needs to change (e.g., it’s time to update the log storage system), there is no need to alter the frontend applications or the means of aggregation.

- Commit log

- Database changes can be published to Kafka, and applications can easily monitor this stream to receive live updates as they happen.

- This changelog stream can also be used for replicating database updates to a remote system, or for consolidating changes from multiple applications into a single database view.

- Durable retention is useful here for providing a buffer for the changelog, so it can be replayed in the event of a failure of the consuming applications.

- Alternately, log-compacted topics can be used to provide longer retention by only retaining a single change per key.

- Stream processing

- Stream processing refers to applications that provide similar functionality to map/reduce processing in Hadoop.

- Hadoop usually relies on aggregation of data over a long time frame, either hours or days. On the other hand, stream processing operates on data in real time, as quickly as messages are produced.

- Stream frameworks allow users to write small applications to operate on Kafka messages, performing tasks such as counting metrics, partitioning messages for efficient processing by other applications, or transforming messages using data from multiple sources.

Kafka internals

Cluster membership

- Kafka uses ZooKeeper to maintain the list of brokers that are currently members of a cluster. Recall the group membership example from ZooKeeper

- Every broker has a unique identifier. Every time a broker process starts, it registers itself with its ID in ZooKeeper by creating an ephemeral znode under the path “/brokers/ids”.

- Kafka brokers, the controller, and some of the ecosystem tools place a watch on that path so that they get notified when brokers are added or removed.

- When a broker loses connectivity to ZooKeeper, the ephemeral znode that the broker created when starting will be automatically removed from ZooKeeper.

- Kafka components that are watching the list of brokers will be notified that the broker is gone.

- Although the znode representing the broker is gone when the broker is stopped, the broker ID still exists in Kafka’s internal data structures.

- This way, if you completely lose a broker and start a brand-new broker with the ID of the old one, it will immediately join the cluster in place of the missing broker with the same partitions and topics assigned to it.

Controller

- The controller is one of the Kafka brokers that, in addition to the usual broker functionality, is responsible for electing partition leaders.

- The first broker that starts in the cluster becomes the controller by creating an ephemeral znode in ZooKeeper called “/controller”.

- When other brokers start, they also try to create this node but receive a “node already exists” exception, which causes them to “realize” that the controller node already exists and that the cluster already has a controller.

- The brokers create a ZooKeeper watch on the controller znode so they get notified of changes to this znode.

- This way, we guarantee that the cluster will only have one controller at a time.

- When the controller broker is stopped or loses connectivity to ZooKeeper, the ephemeral znode will disappear.

- Other brokers in the cluster will be notified through the ZooKeeper watch that the controller is gone and will attempt to create the controller znode in ZooKeeper themselves.

- The first node to create the new controller in ZooKeeper becomes the next controller, while the other nodes will receive a “node already exists” exception and re-create the watch on the new controller znode.

- When the controller first comes up, it has to read the latest replica state map from ZooKeeper before it can start managing the cluster metadata and performing leader elections.

- When the controller notices that a broker left the cluster, it knows that all the partitions that had a leader on that broker will need a new leader.

- It goes over all the partitions that need a new leader and determines who the new leader should be (simply the next replica in the replica list of that partition).

- Then it persists the new state to ZooKeeper and sends information about the leadership change to all the brokers that contain replicas for those partitions.

- Example flow:

- Suppose a Kafka cluster has three brokers: B1, B2, and B3. When the cluster starts, B1 starts first and creates the ephemeral znode /controller in ZooKeeper, becoming the controller. When B2 and B3 start, they try to create the same znode but get a “node already exists” exception, so they know B1 is already the controller and set a watch on /controller. Now, imagine B1 crashes or loses connectivity. Its ephemeral znode disappears, and B2 and B3 are notified via their watches. Both try to create /controller; whichever succeeds first becomes the new controller (say B2), while the other (B3) gets an exception and resets its watch on /controller.

- After B2 becomes the new controller, it first reads the latest replica state from ZooKeeper to understand the current mapping of partitions and their leaders. Suppose the cluster has a topic orders with 3 partitions:

- Partition 0 → replicas [B1, B2, B3], leader was B1

- Partition 1 → replicas [B1, B3, B2], leader was B1

- Partition 2 → replicas [B2, B1, B3], leader was B2

- Since B1 has failed, partitions 0 and 1 need new leaders. B2 examines the replica lists:

- For Partition 0, the next replica in the list after B1 is B2, so B2 becomes the new leader.

- For Partition 1, the next replica after B1 is B3, so B3 becomes the new leader.

- Partition 2 is unaffected because its leader, B2, is still active.

- The controller then updates ZooKeeper with the new leadership information for partitions 0 and 1. It also notifies all brokers that host replicas of these partitions (B2 and B3 for Partition 0, B2 and B3 for Partition 1) about the changes.

- This ensures that producers and consumers can continue sending and receiving messages without disruption. By following this process, Kafka guarantees automatic failover, consistent leadership, and uninterrupted availability of all partitions in the cluster.

A Quick Review:

- Broker as leader:

- Each partition in a topic has exactly one leader at a time.

- A broker can be the leader for multiple partitions, even across multiple topics. So if a broker handles multiple topics, it can simultaneously be the leader for several partitions of different topics.

- Followers replicate the leader’s data for fault tolerance, but only the leader handles reads/writes for that partition.

- Consumers and partitions:

- A consumer in a consumer group can read from one or more partitions, but each partition can be read by only one consumer in the same group at a time.

- For a single topic with multiple partitions, multiple consumers in the same group allow parallel consumption, but each partition is still assigned to only one consumer.

- If a consumer subscribes to multiple topics, it can consume from one or more partitions from each topic, depending on how partitions are assigned to it.

- Example:

- Topic A has 3 partitions: P0, P1, P2. Topic B has 2 partitions: Q0, Q1.

- Broker B1 might be leader for P0 and Q1; B2 leader for P1 and Q0; B3 leader for P2.

- Consumer C1 in a consumer group could be assigned P0 (topic A) and Q0 (topic B), while C2 gets P1 and Q1.

- So, brokers can be leaders for multiple partitions across topics, and consumers can read from multiple partitions across topics, but within a consumer group, each partition is served by only one consumer at a time.

Replication

- Replication is critical because it is the way Kafka guarantees availability and durability when individual nodes inevitably fail.

- As we’ve already discussed, data in Kafka is organized by topics.

- Each topic is partitioned.

- Each partition can have multiple replicas.

- Those replicas are stored on brokers, and each broker typically stores hundreds or even thousands of replicas belonging to different topics and partitions.

- There are two types of replicas.

- Leader replica

- Each partition has a single replica designated as the leader.

- All produce requests go through the leader to guarantee consistency.

- Clients can consume from either the leader replica or its followers.

- Follower replica

- All replicas for a partition that are not leaders are called followers.

- If a leader replica for a partition fails, one of the follower replicas will be promoted to become the new leader for the partition.

- Kafka provides the following reliability guarantees:

- Kafka provides order guarantee of messages in a partition.

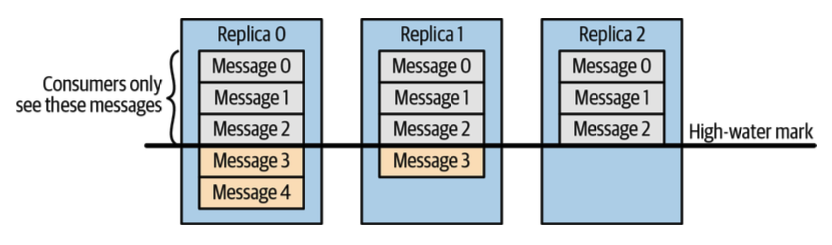

- Produced messages are considered “committed” when they were written to the partition on all its in-sync replicas (but not necessarily flushed to disk). In-sync replicas are the leader and followers that lags within 10 seconds (configurable).

- Messages that are committed will not be lost as long as at least one replica remains alive.

- Consumers can only read messages that are committed.

- Q: Can Kafka consumers read from any replica of a partition, or only from the leader?

- A: In Kafka, each partition has a single leader replica and zero or more follower replicas. By default, consumers read from the leader replica, which guarantees that they see all committed messages in order and avoids inconsistencies. Followers replicate the leader’s data and can serve as read sources only if the system is explicitly configured to allow reading from followers, for example, to balance read load. However, followers that are out-of-sync may not have all committed messages or may lag behind the leader, so reading from them can result in missing or stale data. Therefore, reading from the leader is the default and safest approach, ensuring correctness, ordering, and durability, while followers primarily provide redundancy and high availability in case of leader failure.

Request processing

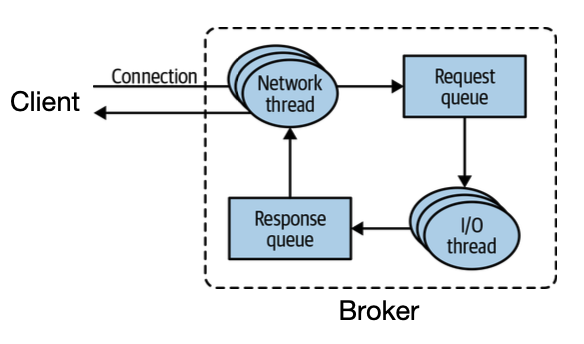

- A Kafka broker processes requests sent to the partition leaders from clients, partition replicas, and the controller.

- Clients always initiate connections and send requests, and the broker processes the requests and responds to them.

- All requests sent to the broker from a specific client will be processed in the order in which they were received This guarantee allows Kafka to behave as a message queue and provide ordering guarantees on the messages it stores.

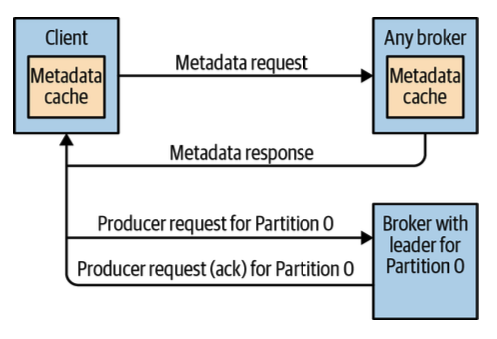

- How do clients know where to send the requests?

- Clients know where to send requests because each partition has a designated leader, and brokers maintain metadata about which broker is the leader for which partition. When a client wants to produce or consume messages, it first fetches the cluster metadata (from ZooKeeper in older versions or from the Kafka bootstrap servers). This metadata includes the list of brokers, topics, partitions, and the leader for each partition. Using this information, the client can send requests directly to the broker that is the leader for the partition it wants to read from or write to.

- This ensures that requests always reach the correct partition leader, maintaining message ordering and consistency guarantees, and reduces unnecessary network hops through other brokers.

- Clients can set an upper/lower bound on the amount of data the broker can return, as well as a timeout.

- Consumers only see messages that were replicated to in-sync replicas.

Physical storage

- The basic storage unit of Kafka is a partition replica.

- Partitions cannot be split between multiple brokers, and not even between multiple disks on the same broker.

- Therefore, the size of a partition is limited by the space available on a single mount point.

- Kafka 3.9 (November 2024) supports “tiered storage”. (see KIP-405)

- The local tier: store the log segments on the local disks. (same as current)

- The remote tier: store the completed log segments on HDFS, S3, … (new)

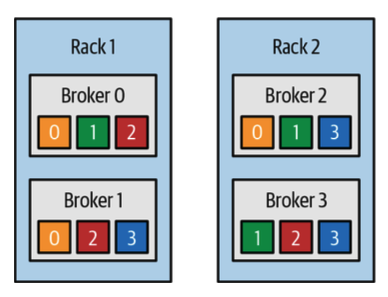

- When you create a topic, Kafka first decides how to allocate the partitions between brokers.

- The default replication factor is 3.

- Users can add or remove replicas even after a topic exists.

- Kafka does not keep data forever. It doesn’t even wait for all consumers to read a message before deleting it.

- Instead, the Kafka administrator configures a retention period for each topic.

- Time-based: how long to store messages before deleting them.

- Space-based: how much data to store before older messages are purged.

- Each partition is split into segments. By default, each segment contains either 1 GB of data or a week of data, whichever is smaller.

- As a Kafka broker is writing to a partition, if the segment limit is reached, it closes the file and starts a new one.

- Each segment is stored in a single data file, which stores Kafka messages and their offsets.

- The format of the data on the disk is identical to the format of the messages that we send from the producer to the broker and later from the broker to the consumers (i.e., the wire protocol).

- This allows Kafka to use a zero-copy method to send messages to clients. Kafka sends messages from the file (or more likely, the Linux filesystem cache) directly to the network channel without any intermediate buffers.

- It also avoids decompressing and recompressing messages that the producer already compressed.

-

Note: Zero-copy is an optimization in which Kafka sends data from disk to the network without multiple memory copies between user space and kernel space. Normally, sending data involves copying from disk to kernel buffers, then to user-space buffers, and back to kernel network buffers before transmission. With zero-copy (using OS features like Linux sendfile), Kafka can send messages directly from the on-disk segment files or the Linux page cache to the network socket. This reduces CPU and memory usage, speeds up message delivery, and works efficiently because Kafka’s on-disk segment format matches the wire protocol, so no data transformation is needed. The wire protocol is the format and rules that define how data is encoded and transmitted over the network between clients and servers.

- Kafka provides flexible message retrieval and retention mechanisms. Consumers can start reading messages from any offset, and to make this efficient, each partition maintains an offset-to-segment index, which maps offsets to their exact position within segment files.

- Additionally, Kafka maintains a timestamp-to-offset index to quickly locate messages by time, which is useful for Kafka Streams and certain failover scenarios.

- For retention, topics can be configured in three ways: delete, which removes messages older than a configured time; compact, which keeps only the latest value for each key; or delete and compact, combining compaction with time-based deletion.

- Note: Both compaction and deletion operate on the messages stored on the brokers for a given topic.

Kafka Producer Flow

- When a producer wants to send messages to a Kafka topic, it first connects to one of the bootstrap brokers configured in its setup. It then requests metadata from the broker, which includes the list of partitions for the topic, the leader broker for each partition, and the replicas for each partition. The producer caches this metadata so that it can send records directly to the correct leader broker for the target partition.

- If the leader changes due to a failover or if the cached metadata expires, the producer automatically refreshes the metadata by querying the brokers again. This ensures that the producer always knows which broker to contact for each partition and guarantees that messages are sent to the appropriate leader.

Kafka Consumer - Commits and offsets

- In Kafka, consumers track which messages they have read by maintaining offsets, which represent their current position in each partition. Whenever a consumer calls poll(), it retrieves all messages from the last committed offset up to the latest.

- Unlike traditional message queues, Kafka does not track individual acknowledgments for each message. Instead, a consumer commits offsets, which updates a special internal topic called __consumer_offsets. This commit records the last successfully processed message in a partition, implicitly marking all prior messages as processed. By default, Kafka consumers commit offsets automatically every few seconds, but this can be disabled to allow explicit commits, which helps prevent message loss or duplication during rebalancing events.