Hadoop Distributed File System (HDFS)

- The Hadoop Distributed File System (HDFS) is a distributed file system designed to run on commodity hardware.

- It provides an interface similar to a POSIX file system (files and directories), but with relaxed requirements.

- It scales up to 100+ PB of storage and thousands of servers, supporting close to a billion files and blocks.

- Small gist about POSIX: POSIX (Portable Operating System Interface) is a standard that defines how file systems and operating systems should behave, ensuring consistency across Unix-like systems such as Linux and macOS. In file systems, POSIX specifies that every write must be immediately visible to all readers, files can be modified at any position (supporting random writes), and operations like open, close, read, write, delete, and rename must appear atomic and consistent. It also enforces strict locking and consistency rules for concurrent access, ensuring multiple processes can safely read and write files simultaneously without data corruption.

Assumptions and goals:

- Commodity hardware: Hardware failure is the norm rather than the exception. An HDFS instance may consist of thousands of servers. Each component has a non-trivial probability of failure. As a result, some component of HDFS is always non-functional. Therefore, detection of faults and quick, automatic recovery from them is a core architectural goal of HDFS.

- Streaming data access: HDFS is designed more for batch processing (e.g., MapReduce) rather than interactive use by users. The emphasis is on high throughput of data access rather than low latency of data access. Therefore, some POSIX semantics has been relaxed to increase data throughput rates.

- Large datasets: A typical file in HDFS is gigabytes to terabytes in size. Thus, HDFS is tuned to support large files. It should provide high aggregate data bandwidth. It should scale to hundreds of nodes in a single cluster. It should support tens of millions of files in a single instance.

- Simple coherency model: HDFS applications need a write-once-read-many (WORM) access model for files. Files cannot be modified except for appends and truncates. This design avoids complex consistency and synchronization problems that arise from random writes or concurrent updates. By restricting how data can change, HDFS simplifies data coherency management across replicas and achieves higher throughput for large-scale, sequential data access. Ex: a MapReduce application or a web crawler application fits perfectly with this model.

- Moving computation is cheaper than moving data: A computation requested by an application is much more efficient if it is executed near the data it operates on, especially when the size of the dataset is huge. This minimizes network congestion and increases the overall throughput of the system. So, it is often better to migrate the computation closer to where the data is located rather than moving the data to where the application is running. HDFS provides interfaces for applications to move themselves closer to where the data is located.

-

Portability across heterogeneous hardware & software platforms: HDFS has been designed to be easily portable from on platform to another. It is implemented as a user-level filesystem in Java. Because it’s written in Java, it runs anywhere a Java Virtual Machine (JVM) is available, such as Linux, Windows, or macOS. The JVM acts as a layer between the Java program and the underlying operating system, translating Java instructions into native instructions the OS can execute. And unlike traditional file systems built directly into the operating system kernel, HDFS is a user-level file system, meaning it operates as a regular application process instead of requiring kernel-level changes. This makes it easier to install, update, and move between environments. This facilitates widespread adoption of HDFS as a platform of choice for a large set of applications.

- A gist on how Java program is executed from code to instructions in device: When a Java program like HDFS is executed, the process starts with writing source code in .java files, which is then compiled by the Java compiler (javac) into bytecode stored in .class files. These class files, along with necessary resources and configuration, are often bundled into a JAR (Java ARchive) file for easy distribution and deployment. On the target machine, the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) loads the bytecode from the class or JAR files and interprets or Just-In-Time (JIT) compiles it into native machine instructions that the operating system and hardware can execute. This abstraction provided by the JVM allows the same Java program or JAR file to run on any device or OS with a JVM installed, making Java programs, including HDFS, portable across heterogeneous platforms.

Architecture

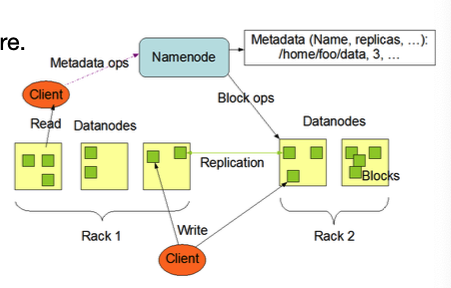

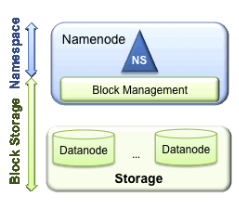

- HDFS has a master-workers architecture.

- One NameNode: Manages the file system metadata.

- Many DataNodes: Stores the actual data blocks

- The HDFS namespace is a hierarchy of files and dirs. It supports user quotas and access permissions.

- The file content is split into large blocks (typically 128MB). Large blocks can minimize seek time. A file smaller than a block does not occupy a full block’s worth of storage.

- Clarification: Disk seek time is the delay caused by moving the read/write head to the data location. By using large blocks, HDFS allows more data to be read sequentially once the head is positioned, reducing the number of seeks needed. Fewer, larger blocks overall improve throughput for reading large files, which is especially beneficial for batch processing like MapReduce.

- Benefits of blocks as primitive unit:

- Support very large files, even larger than any single disk in the network.

- Simplify storage management and decouple metadata from blocks.

- Blocks can be replicated for fault tolerance and availability.

- NameNode:

- The NameNode manages the HDFS namespace.

- It maintains the file system tree and the metadata for all the files and directories. This information is persisted on disk. The NameNode loads the entire namespace image into memory at startup.

- The NameNode also knows where every block is located. This information is in memory only, not persisted on disk. It can be reconstructed from DataNodes when the system starts (via heartbeats).

- Without the NameNode, the file system cannot be used.

- DataNode:

- DataNodes are the workhorses of HDFS.

- Each block is independently replicated at multiple DataNodes. An application can specify the number of replicas of a file that should be maintained by HDFS. It is called the replication factor of that file (typically 3).

- DataNodes store and retrieve blocks when asked by clients or the NameNode.

- DataNodes sends heartbeats to the NameNode (typically every 3 seconds).

- DataNodes also report to the NameNode periodically with the lists of blocks they are storing (at startup and every hour).

- HDFS client:

- The HDFS client is a library that exports the HDFS file system interface.

- Applications access the file system using the HDFS client.

- The user application does not need to know that the filesystem metadata and storage are on different servers, and that blocks have multiple replicas.

- However, the block locations are exposed to the client, so that applications like MapReduce can schedule tasks to where the data are located.

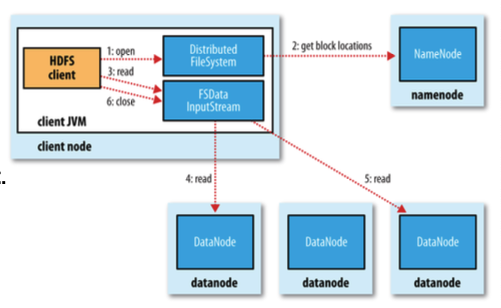

- Reading a file

- First, the HDFS clients asks the NameNode for the list of DataNodes that host replicas of the blocks of the file.

- The list is sorted by the network topology distance from the client.

- Then the client contacts a DataNode directly and requests the transfer of the desired block.

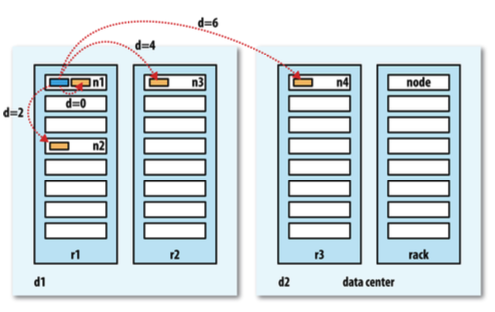

- Network topology

- The distance between two nodes is the sum of their distances to their closest common ancestor.

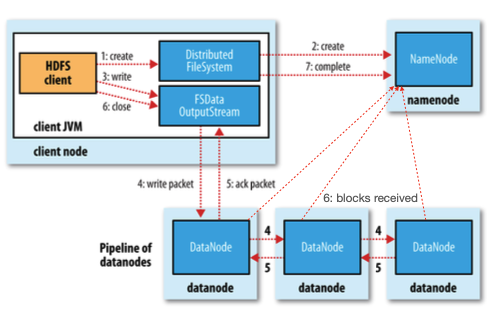

- Writing a file

- First, the HDFS client asks the NameNode to choose DataNodes to host replicas of the first block of the file.

- The client organizes a pipeline from node to node and sends the data.

- When the first block is filled, the client requests new DataNodes to be chosen to host replicas of the next block. A new pipeline is organized, and the client sends the further bytes of the file.

- Choice of DataNodes for each block is likely to be different.

- Block placement

- Trade-off between minimizing the write cost, and maximizing data reliability, availability and aggregate read bandwidth.

- #1: same node as the client.

- #2: different rack from #1.

- #3: same rack as #2, but different node.

- This default strategy gives a good balance among:

- Reliability: blocks are stored on two racks.

- Write bandwidth: writes only have to traverse a single network switch.

- Read performance: choice of two racks to read from.

- Block distribution across the cluster: clients only write a single block on the local rack.

- Trade-off between minimizing the write cost, and maximizing data reliability, availability and aggregate read bandwidth.

- The single-writer, multiple-reader model

- The HDFS client that opens a file for writing is granted a lease (lock) for the file; no other client can write to the file. The writer’s lease doesn’t prevent other clients from reading the file; a file may have many concurrent readers.

- The writing client periodically renews the lease by sending a heartbeat to the NameNode.

- When the file is closed, the lease is revoked.

- Coherency model

- A coherency model for a filesystem describes the data visibility of reads and writes for a file.

- HDFS trades off some POSIX semantics for performance.

- After creating a file, it is visible in the filesystem namespace. However, the last block’s content may not be visible until the file is closed.

- If the client needs the visibility guarantee, it can call hflush() explicitly. It guarantees that the data written up to that point in the file has reached all the DataNodes in the write pipeline and is visible to all new readers. However, the data may be in the DataNodes’ memory only.

- To guarantee that the DataNodes have written the data to disk, call hsync().

- So, in short: HDFS’s coherency model is tied to its block structure - a file is visible immediately, but the last block may be partially written. Visibility and durability of that block are controlled explicitly via hflush() (memory) and hsync() (disk).

Resilience

- NameNode

- NameNode persists checkpoint + journal on disk.

- Checkpoint: the file system tree and metadata at the specific point in time.

- Journal (“edit log”): All changes to HDFS since the last checkpoint.

- CheckpointNode periodically combines the existing checkpoint and journal into a new checkpoint and sends it back to NameNode, which truncates the journal.

- BackupNode maintains a read-only, synchronized namespace state of the NameNode without block locations.

- DataNode

- When writing a file, the client computes the checksum for each data block. DataNodes store the checksums locally in a metadata file.

- When reading a file, the client verifies the checksum. If a block is corrupted, the client notifies the NameNode and fetches another replica of the block.

- If a DataNode fails or a block is corrupted:

- Data can be retrieved from another DataNode storing the block replica.

- The NameNode marks the replica as unavailable/corrupt.

- The NameNode schedules creation of new replicas on other DataNodes.

- A small gist about checksum: A checksum is a small value computed from a block of data to verify its integrity. It is generated by applying a hash function (e.g., CRC32) to a block of data. The resulting number changes if even a single bit of the data changes. In HDFS, when data is written, a checksum is generated and stored alongside it. During reads, the checksum is recalculated and compared with the stored value to detect any corruption. If they don’t match, HDFS identifies the block as damaged and retrieves a healthy replica from another DataNode. This ensures reliable and consistent data storage across the system.

Optimizations

- Block caching

- Frequently accessed blocks may be explicitly cached in DataNode’s memory.

- By default, a block is cached in only “one” DataNode’s memory. This # of DataNode’s is configurable on a per-file basis.

- Users or applications tell the NameNode which files to cache, and for how long.

- Applications (e.g., MapReduce) can schedule tasks on the DataNode where a block is cached, for increased read performance.

- The NameNode maintains which DataNodes holds the cache of a specific block, along with other bookkeeping information.

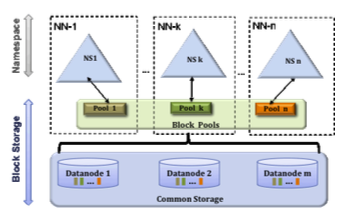

- HDFS federation

- On a very large clusters with many files, the NameNode’s memory becomes the limiting factor for scaling. This is because the NameNode keeps a reference to every file and block in the filesystem in memory.

- HDFS federation allows a cluster to scale by adding NameNodes. Each NameNode manages a portion of the filesystem namespace(its own part of the directory tree).

- Under federation, each NameNode manages a namespace volume, which contains the metadata for the namespace.

- Namespace volumes are independent of each other. NameNodes do not communicate with one another. If one NameNode fails, the availability of the namespaces managed by other NameNodes will not be affected.

- Under federation, each NameNode also manages a block pool, which contains all the blocks for the files in the namespace.

- Block pool storage is not partitioned among DataNodes. DataNodes register with each NameNode in the cluster and store blocks from multiple block pools.

- The conceptual flow: In very large HDFS clusters, the single NameNode becomes a scalability bottleneck because it must keep metadata for every file and block in memory. HDFS Federation solves this by allowing multiple independent NameNodes, each managing its own namespace volume—a separate portion of the filesystem’s directory structure. Along with the namespace, each NameNode also manages a corresponding block pool, which contains all the physical data blocks belonging to files in that namespace. The DataNodes in the cluster are shared among all NameNodes and register with each of them, storing blocks from multiple block pools simultaneously. Note that the DataNode storage is shared physically, but logically partitioned into multiple block pools - one per NameNode. This design separates metadata management from physical storage, allowing the system to scale horizontally, isolate faults (a failure in one NameNode doesn’t affect others), and support multiple namespaces while still using the same underlying DataNodes for efficient shared storage.

- HDFS High Availability (HA)

- Although checkpoints of the NameNode protect against data loss, they don’t provide high availability of the filesystem.

- The NameNode is still a single point of failure (SPOF).

- If the NameNode fails or performs routine maintenance, the entire Hadoop ecosystem becomes out of service until a new NameNode is brought online. Manual intervention is required. On large clusters with many files and blocks, starting a new NameNode can take 30 minutes or more.

- With HDFS high availability (HA), there are a pair of NameNodes in an active-standby configuration.

- If the Active NameNode fails, the Standby NameNode takes over its duties to continue servicing client requests without a significant interruption (~1 minute).

- Even if the Standby NameNode is down when the Active NameNode fails, the sysadmin can still start the Standby NameNode from cold (same as non-HA).

- HDFS High Availability (HA) requires a few architectural changes:

- The NameNodes must use highly available shared storage (e.g., NFS or the Quorum Journal Manager) to share the journal.

- DataNodes must send block reports to both NameNodes because the block mappings are stored in a NameNode’s memory, not on disk.

- Clients must be configured to handle NameNode failover transparently.

- Checkpoint/BackupNode’s role is subsumed by the Standby NameNode, which takes periodic checkpoints of the Active NameNode’s namespace.

- The transition from the Active NameNode to the Standby NameNode is managed by a failover controller. By default, it uses ZooKeeper to ensure that only one NameNode is active.

- Each NameNode runs a lightweight failover controller process, which monitors its NameNode for failures (using a simple heartbeating mechanism) and triggers a failover should a NameNode fail.

- Failover may also be initiated manually (e.g., for routine maintenance). This is known as a graceful failover, since the failover controller arranges an orderly transition for both NameNodes to switch roles.

- However, in the case of an ungraceful failover, it’s impossible to be sure that the failed NameNode has stopped running.

- For example, a slow network or a network partition can trigger a failover transition, even though the previous Active NameNode is still running and thinks it’s still the Active NameNode.

- The HA implementation employs fencing methods to ensure that the previous Active NameNode is prevented from doing any damage or causing corruption.

- Have you heard of STONITH (shoot the other node in the head)?

- Q: How does each NameNode monitor failures in HDFS High Availability? A: Each NameNode runs a lightweight Failover Controller (ZKFC) that monitors the health of its own NameNode using a heartbeat mechanism. Both ZKFCs communicate with ZooKeeper, which coordinates and ensures that only one NameNode is Active at any time. If the Active NameNode fails, ZooKeeper triggers the Standby’s ZKFC to take over and become Active, ensuring continuous service.

- Q: What are fencing methods and why are they needed? A: Fencing is a safety mechanism used during failover to prevent the old Active NameNode from making changes after a Standby takes over. This is crucial because the old Active might still be running but disconnected (e.g., due to a network partition). Fencing isolates or disables the old node, commonly by killing its process, revoking access to shared storage, or even powering off the machine, ensuring that only one NameNode can write to the filesystem metadata, preventing corruption.

- Q: What is STONITH and how is it related? A: STONITH (Shoot The Other Node In The Head) is a type of fencing where the old node is forcibly shut down before the Standby takes over. In HDFS HA, it guarantees that the previous Active NameNode cannot interfere with the new Active, providing a strong safeguard against simultaneous writes and ensuring data consistency.

- Balancer

- Over time, the distribution of blocks across DataNodes can become unbalanced. An unbalanced cluster can affect locality for applications (e.g., MapReduce), and it puts a greater strain on the highly utilized DataNodes.

- The balancer program is a daemon…

- It redistributes blocks by moving them from overutilized DataNodes to underutilized DataNodes.

- It adheres to the block replica placement policy that makes data loss unlikely by placing block replicas on different racks.

- It minimizes inter-rack data copying in the balancing process.

- Q: What is the HDFS Balancer daemon and where does it run? A: The Balancer is a separate user-level daemon that runs on the Hadoop cluster, typically launched from a client node or NameNode host. It is not part of the NameNode or DataNode processes.

- Q: How does the Balancer work? A: It communicates with the NameNode to get cluster metadata, identifies overutilized and underutilized DataNodes, and moves blocks accordingly. It follows replica placement rules to avoid data loss and minimize inter-rack transfers.

- Q: What happens if there are failovers or crashes? A: If the Active NameNode fails, the Balancer reconnects to the new Active NameNode. If a DataNode fails, block moves to that node are paused or rescheduled. If the Balancer itself crashes, it can be restarted safely, resuming block moves without affecting cluster integrity.

- Q: If the Balancer runs outside HDFS, how does it access block information? A: The Balancer accesses block information through the HDFS client interface. It communicates with the NameNode using HDFS RPC APIs to retrieve metadata about all blocks, including which DataNodes store them and their disk utilization.

- Q: How does the Balancer move blocks between DataNodes? A: After obtaining metadata from the NameNode, the Balancer schedules block transfers between DataNodes. The actual data movement happens directly between DataNodes, while the Balancer only coordinates the process based on the metadata it received.

- Q: Why can the Balancer manage blocks even though it’s outside HDFS processes? A: Because it uses the official HDFS client APIs, the Balancer can read cluster metadata, monitor utilization, and orchestrate block redistribution without being part of the NameNode or DataNode processes.

- Block scanner

- Every DataNode runs a block scanner, which periodically verifies all the blocks stored on the DataNode.

- This allows bad blocks to be detected and fixed before they are read by clients.

- The scanner maintains a list of blocks to verify and scans them one by one for checksum errors.

- It also employs a throttling mechanism to preserve disk bandwidth on the DataNode. This throttling mechanism limits the speed or resource usage of the block scanner so it does not overwhelm the DataNode’s disk or network.

Usage

- The Hadoop FS shell provides commands that directly interact with HDFS.

- Ex: hadoop fs -command

Doubt: Is HDFS C+P or A+P under CAP theorem?

- From the sources, I feel it falls under C+P. One of the answer/argument that makes sense is below.

- The cluster is consistent as long as the primary namenode is available. when a namenode becomes unavailable, the secondary namenode gets queried, however writes can become delayed / rejected. so despite not being an explicit “single point of failure”, it will still affect the “perceived availability and/or consistency of data” to external interfaces. At the end of the day, the primary namenode handles data consistency, and is synced to the secondary namenode (i.e. it does not require consensus). This is only “partially available” in practice.