Apache ZooKeeper

Introduction

- So far in this semester, we have been studying large-scale distributed data processing systems.

- Today is different. We will study how to build general distributed applications using Hadoop’s distributed coordination service, ZooKeeper.

Distributed coordination

- What should an autonomic service provide?

- Self-configuring: All configuration should happen with little or no intervention by the user.

- Self-healing: When a process, service, or node stops working, it should repair itself.

- Self-protecting: The service should continually assess its own health. Redundant, cooperating health checkers can health-check each other.

- Self-optimizing: The service should continually assess its own performance. Perform load-balancing operations or request resources to maintain a desired level of performance.

- Why is building distributed applications hard?

- The main reason is partial failure.

- When a message is sent across the network between two nodes and the network fails, the sender does not know whether the receiver got the message.

- It may have gotten through before the network failed.

- Or it may not have gotten through at all.

- Or perhaps the network is just too slow, and the message is just delayed?

- The only way that the sender can find out what happened is to reconnect to the receiver and ask it.

- This is partial failure: when we don’t even know if an operation failed.

- Distributed programming is fundamentally different from local programming.

- Without fresh, accurate, and timely information, it’s very difficult to identify the root cause of the failure in realtime.

- Network failure.

- Process failure.

- Shared resource failure (e.g., data store).

- Physical machine failure.

- Virtual machine failure.

- Configuration errors.

- How can ZooKeeper help?

- ZooKeeper can’t make partial failures go away: Partial failures are intrinsic to distributed systems.

- ZooKeeper does not hide partial failures, either: What ZooKeeper does is give you a set of tools to build distributed applications that can safely handle partial failures.

ZooKeeper

Characteristics

- ZooKeeper is simple: At its core, ZooKeeper is a stripped-down filesystem that exposes a few simple operations.

- ZooKeeper is expressive: The ZooKeeper primitives are a rich set of building blocks that can be used to build many systems.

- ZooKeeper is highly available: ZooKeeper runs on a collection of machines with no single point of failure.

- ZooKeeper facilitates loosely coupled interactions: Participants do not need to know about one another or exist simultaneously.

- ZooKeeper is a library: ZooKeeper has a vibrant open-source community and rich documentation.

Data model

- Znodes

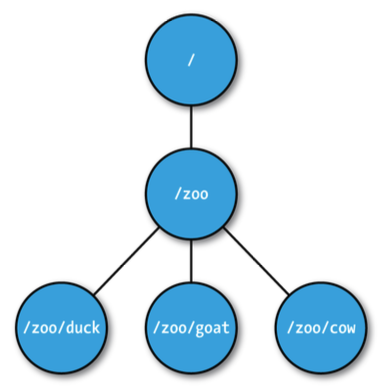

- ZooKeeper maintains a hierarchical tree of nodes called znodes.

- A znode stores data and has an associated access-control list and version number.

- The default size limit of the stored data is 1MB. This is because ZooKeeper is designed for coordination (which typically uses small datafiles), not high-volume data storage.

- Accessing the data associated with a znode is atomic.

- A client reading the data will either receive the entire data or fail.

- A client writing the data will replace all the data with a znode or fail.

- There is no such thing as a partial read/write.

- ZooKeeper does not support an append operation. These characteristics contrast with HDFS. HDFS is designed for high-volume data storage with streaming data access and provides an append operation.

- In ZooKeeper, the statement “no append operation” means that you cannot add data incrementally to a znode. When writing to a znode, the entire content must be replaced in a single operation; partial writes or incremental appends are not supported.

- Znodes are referenced by paths.

- A path is a slash-delimited Unicode string, similar to a filesystem path.

- Paths must be absolute, i.e., begin with a slash.

- All paths are canonical, i.e., each path has a single representation. Paths do not undergo resolution. You cannot use “.” or “..” as in a filesystem path.

- The path “/zookeeper” is reserved to store management information.

- There are two types of znodes. Ephemeral znode: It will be deleted by the ZooKeeper service when the client that created it disconnects, either explicitly or because the client terminates for whatever reason. And Persistent znode: It will not be deleted when the client disconnects. The type of a znode is set at creation time and may not be changed later.

- Ephemeral znodes

- An ephemeral znode is automatically deleted by ZooKeeper when the creating client’s session ends.

- An ephemeral znode may not have children, not even ephemeral ones. If ephemeral nodes were allowed to have children, it would create complications when the parent is deleted, what happens to the children? To avoid this problem, ZooKeeper enforces that ephemeral znodes are always leaf nodes.

- Even though ephemeral nodes are tied to a client session, they are visible to all clients (subject to their access-control list policies).

- Ephemeral znodes are ideal for building applications that need to know when certain distributed resources are available.

- Persistent znodes

- A persistent znode is not tied to the client’s session.

- It is deleted only when explicitly deleted by a client. Not necessarily by the client that created it.

- A persistent node can have children, similar to a directory in a filesystem.

- Sequence numbers

- A sequential znode is given a sequence number by ZooKeeper as a part of its name.

- If a znode is created with the sequential flag set, then the value of a monotonically increasing counter is appended to its name. The counter is maintained by its parent znode.

- Sequence numbers can be used to impose a global ordering on events in a distributed system and may be used by the client to infer the ordering.

- Example: if the client asks to create a sequential znode named “/a/b-”, the service may create a znode named “/a/b-3” and later another znode “/a/b-5”.

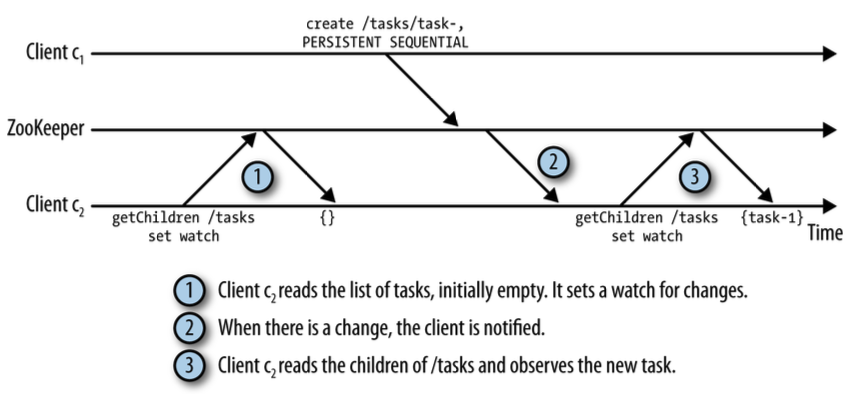

- Watches

- Watches allow clients to get notifications when a znode changes in some way.

- The client can set a watch with read operations on the ZooKeeper service. Watches are triggered by write operations on the ZooKeeper service.

- Watches are triggered only once. To receive multiple notifications, a client needs to reregister the watch.

- For example, a client can call exists on a znode with a watch; if the znode does not exist, the call returns false, but later, when another client creates that znode, the watch fires and the first client is notified.

- Watches are set on specific znodes, not on the entire ZooKeeper service.

- You attach a watch to a znode when performing a read operation (exists, getData, or getChildren).

- The watch is only triggered by changes to that particular znode (or its children, in the case of getChildren).

- A client can have multiple watches simultaneously, each on different znodes or different aspects of the same znode.

- Each watch is one-time: once triggered, it must be reregistered if the client wants future notifications.

- So at any given time, a client can be watching many znodes, receiving multiple notifications as changes occur—but each individual watch only fires once.

Operations

- Overview

-

create: Create a znode (the parent znode must already exist). -

delete: Delete a znode (the znode must not have any children). -

exists: Tests whether a znode exists and retrieves its metadata. -

getACL, setACL: Get/set the access-control list of a znode. -

getChildren: Get a list of the children of a znode. -

getData, setData: Get/set the data associated with a znode. -

sync: Synchronize a client’s view of a znode with ZooKeeper.- It ensures that any read operation after sync reflects the most up-to-date data for that znode, even in a distributed system with multiple clients and servers.

- Essentially, it forces the client to catch up with all recent updates that may have been applied by other clients or nodes, providing a consistent and current view of the znode’s data.

-

syncis session-wide, not per-znode, but it’s usually used to ensure freshness before reading a specific znode.

-

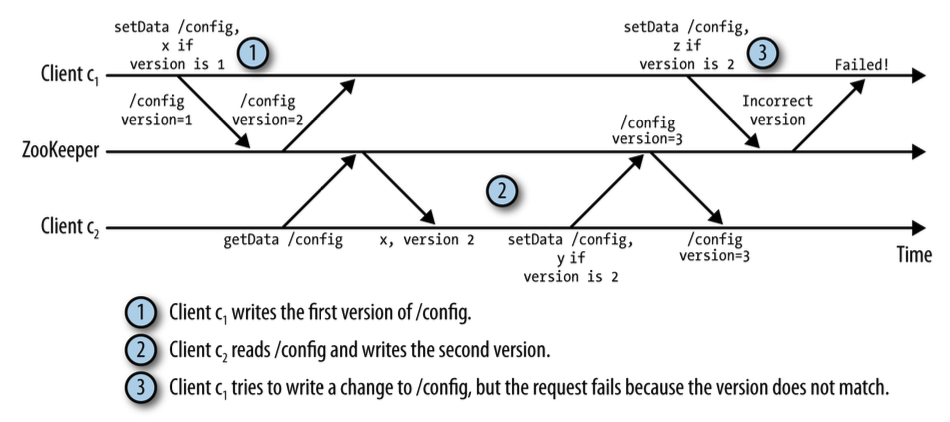

- Version number

- The exists operation returns the version number in the znode’s metadata.

- Update operations (delete, setData) in ZooKeeper are conditional and nonblocking.

- The client has to specify the version number of the znode that is being updated.

- If the version number does not match, the update will fail. It means that another process updated the znode in the meantime.

- This is an optimistic concurrency mechanism that allows clients to detect conflicts over znode modification without locking.

- The version check can be bypassed by using a version number of -1.

- Difference from filesystems

- Although ZooKeeper can be viewed as a filesystem, it does away with some filesystem primitives for simplicity.

- In ZooKeeper, files are small and are written and read in their entirety.

- There is no need to provide open, close, or seek operations.

- Therefore, ZooKeeper does not use handles to access znodes.

- Each operation includes the full path of the znode being operated on.

- The sync operation is also different from fsync in a filesystem.

- Writes in ZooKeeper are atomic and does not need to be synced.

- The sync operation is there to allow a client to catch up with the latest state.

- Q: What does it mean when ZooKeeper says “writes are atomic and do not need to be synced,” even though it runs on many machines?

- A: In ZooKeeper, a write operation (such as create, delete, or setData) is atomic, meaning it either fully succeeds or fully fails—there is no partial update that clients can observe. Although ZooKeeper is a distributed system running on multiple machines, it uses a consensus protocol (ZAB) to ensure that every write is agreed upon, replicated to a majority of servers, and committed in the same order before the client receives a success response. Because durability and ordering are already guaranteed internally by this protocol, the client does not need to call a filesystem-style fsync to force data to disk. ZooKeeper’s sync operation is therefore not about making writes durable; instead, it allows a client to catch up and ensure its read view reflects the latest committed state.

- Multiupdate

- ZooKeeper also provides the multi operation that batches together multiple primitive operations into a single unit that either succeeds or fails in its entirety.

- Multiupdate is useful for building structures that maintain some global invariant.

- Example: an undirected graph.

- Each vertex in the graph is represented as a znode.

- We need to update two znodes to add or remove an edge.

- Batching the updates on the two znodes into one multi operation ensures that the update is atomic.

- Synchronous and asynchronous API

- ZooKeeper provides both synchronous and asynchronous APIs for all operations to suit different programming needs. In the synchronous API, a call (such as exists) blocks until the operation completes and directly returns a result, typically a Stat object or null, or throws an exception on failure. In contrast, the asynchronous API is non-blocking: the client issues the request and continues execution, and ZooKeeper later delivers the result via a callback method (processResult), which includes the return code, path, context, and result data. This allows applications to handle ZooKeeper operations efficiently without blocking threads, which is especially useful in high-concurrency or event-driven systems.

- A callback is a function (or method) that you provide to an API so it can be invoked later when an asynchronous operation completes. Instead of blocking and waiting for a result, the program continues running, and when the operation finishes, the system “calls back” your function with the result (success, failure, or data). In ZooKeeper, callbacks are used in asynchronous APIs to deliver operation results—such as status codes and metadata—once the server has processed the request.

- Watch triggers

- Read operations (exists, getChildren, getData) may have watches set on them.

- The watches are triggered by write operations (create, delete, setData).

- Operations on the access-control list (getACL, setACL) do not participate in watches.

- When a watch is triggered, a watch event is generated, which includes the path of the znode that wa. s involved in the event.

- The watch event does not provide the changed data itself.

- To discover the data, the client needs to reissue a read operation.

- The watch event’s type depends both on the watch and the operation that triggered it.

- A watch set on an exists operation will be triggered when the znode being watched is created, deleted, or has its data updated.

- A watch set on a getData operation will be triggered when the znode being watched is deleted or has its data updated.

- A watch set on a getChildren operation will be triggered when a child of the znode being watched is created or deleted, or when the znode itself is deleted.

- Access-control lists

- A znode can be created with an access-control list, which determines who can perform certain operations on it.

- The client identifies itself to ZooKeeper using an authentication scheme.

- Employing authentication and access-control lists is optional.

Implementation

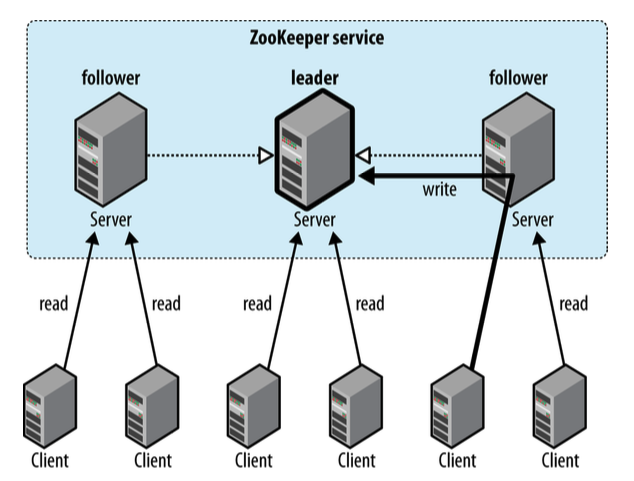

- Ensemble

- ZooKeeper runs on a cluster of machines called an ensemble.

- ZooKeeper achieves high availability through replication, and can provide a service as long as a majority of the machines in the ensemble are live.

- Example: a 5-node ensemble can tolerate at most 2 node failures. It is usual to have an odd number of machines in an ensemble.

- Note: it is critical that ZooKeeper can perform its functions in a timely manner. Therefore, ZooKeeper should run on machines that are dedicated to ZooKeeper alone. Having other applications contend for resources can cause ZooKeeper’s performance to degrade significantly.

- Conceptually, ZooKeeper is very simple.

- All it has to do is ensure that every modification to the tree of znodes is replicated to a majority of the ensemble.

- If a minority of the machines fail, then at least one machine will survive with the latest state.

- The other remaining replicas will eventually catch up with this state.

- Zab

- ZooKeeper uses a protocol called Zab that runs in two phases, which may be repeated indefinitely.

- Phase 1: Leader election:

- The machines in an ensemble go through a process of electing a distinguished member called the leader.

- The other machines are called followers.

- This phase is finished once a majority of followers (called “quorum”) have synchronized their state with the leader.

- Phase 2: Atomic broadcast:

- All write requests are forwarded to the leader.

- The leader then broadcasts the update to the followers.

- When a majority have persisted the change, the leader commits the update, and the client gets a response saying the update succeeded.

- The protocol for achieving consensus is designed to be atomic, so a change either succeeds or fails. It resembles a two-phase commit protocol (2PC).

- What if the leader fails?

- If the leader fails, the remaining machines hold another leader election and continue as before with the new leader.

- If the old leader later recovers, it then starts as a follower.

- Leader election is very fast (~200ms), so performance does not noticeably degrade during an election.

- Replicated database

- Each zookeeper replica maintains an in-memory database containing the entire znode tree.

- Writes: All machines in the ensemble first write updates to disk, and then update their in-memory copies of the znode tree.

- Reads: Read requests may be serviced from any machine. Read requests are very fast because they involve only a lookup from memory.

Consistency

- Understanding consistency

- In ZooKeeper, a follower may lag the leader by a number of updates.

- This is because only a majority and not all members of the ensemble need to have persisted a change before it is committed.

- A client has no control whether it is connected to a leader or a follower, and cannot even know this.

- ZooKeeper transaction ID

- Every update made to the znode tree is given a globally unique identifier, called a zxid (i.e., ZooKeeper transaction ID).

- In ZooKeeper, updates are totally ordered. If zxid is less than , then happened before according to ZooKeeper.

- Consistency guarantees

- Guarantee 1: Sequential consistency

- Updates from any particular client are applied in the order that they are sent. If a client updates the znode

zto the valuea, and in a later operation, itzupdates to the valueb, then no client will ever seezwith valueaafter it has seen it with value b (if no other updates are made toz).

- Updates from any particular client are applied in the order that they are sent. If a client updates the znode

- Guarantee 2: Atomicity

- Updates either succeed or fail. If an update fails, no client will ever see it.

- Guarantee 3: Single system image

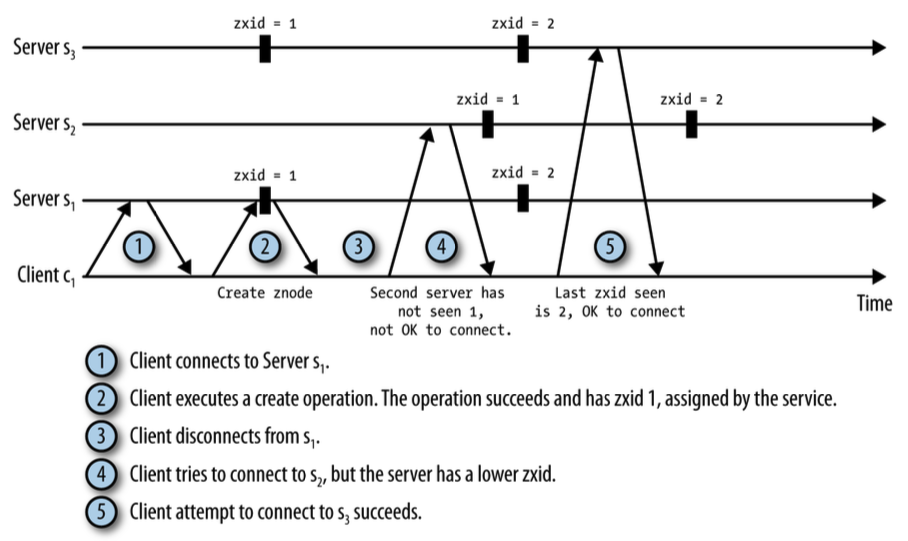

- A client will see the same view of the system, regardless of the server it connects to.

- If a client connects to a new server during the same session, it will not see an older state of the system than the one it saw with the previous server.

- When a server fails and a client tries to connect to another in the ensemble, a server that is behind the one that failed will not accept connections from the client until it has caught up with the failed server.

- Guarantee 4: Durability

- Once an update has succeeded, it will persist and will not be undone.

- Update will survive server failures.

- Guarantee 5: Timeliness

- The lag in any client’s view of the system is bounded, so it will not be out of date by more than some multiple of tens of seconds.

- Rather than allow a client to see data that is very stale, a server will shut down, forcing the client to switch to a more up-to-date server.

- Guarantee 1: Sequential consistency

- (In-)consistency across clients

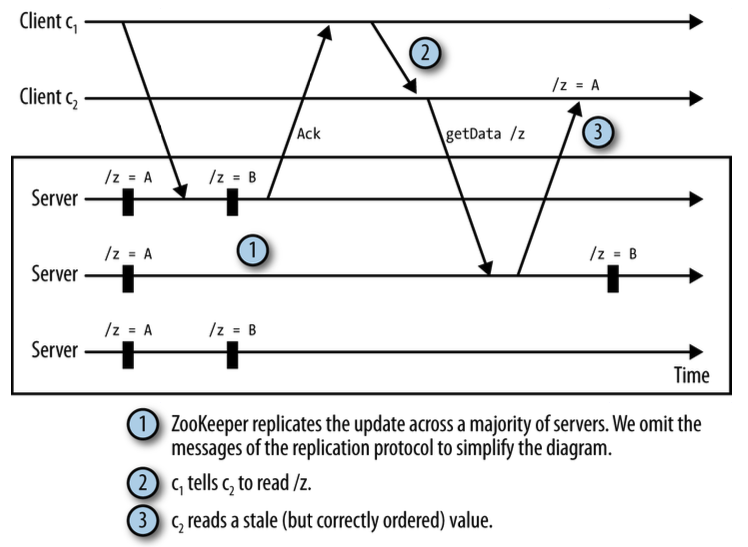

- For performance reasons, reads are satisfied from a ZooKeeper server’s memory and do not participate in the global ordering of writes.

- ZooKeeper does not provide simultaneously consistent cross-client views.

- It is possible for two clients to observe updates at different times.

- If two clients communicate outside ZooKeeper (“hidden channel”), the difference becomes apparent.

- If a client need to catch up with the latest state, the sync operation forces the ZooKeeper server to which the client is connected to catch up with the leader.

- Gist: This means that ZooKeeper optimizes reads by serving them locally, without coordinating them through the global consensus protocol that orders writes. Concretely, when a client issues a read, the ZooKeeper server it is connected to simply returns the value from its in-memory state, instead of synchronizing with the leader or other servers. Because of this, reads are not totally ordered with respect to writes across the entire ensemble. As a result, two clients connected to different servers may temporarily see different versions of the same znode, even though all writes themselves are globally ordered and atomic. This design trades strict read consistency for low latency and high throughput, and clients that need the most up-to-date view can explicitly call sync to force their server to catch up with the leader before reading.

Sessions

- Client startup

- A ZooKeeper client is configured with the list of servers in the ensemble.

- On startup, it tries to connect to one of the servers in the list.

- If the connection fails, it tries another server in the list, and so on, until it either successfully connects to one of them or fails because all ZooKeeper servers are unavailable.

- Once a connection has been made with a ZooKeeper server, the server creates a new session for the client.

- Q: Can a ZooKeeper server handle multiple client sessions simultaneously?

- A: Yes, a ZooKeeper server can manage multiple client sessions at the same time. Each connected client is assigned a unique session that tracks ephemeral znodes, watches, and session timeouts. The server maintains the session state for all clients in memory, allowing it to serve many clients concurrently. If a client disconnects temporarily, its session can remain active for the configured timeout period, enabling the client to reconnect without losing ephemeral nodes or watches. Thus, a single ZooKeeper server is designed to handle multiple client sessions efficiently, while the ensemble as a whole provides scalability and fault tolerance.

- Session timeout

- In ZooKeeper, the client specifies the session timeout when connecting to the ensemble by sending a requested timeout value during the handshake. The server may adjust this value based on its configuration and load, but generally tries to honor the client’s request within allowed limits. This timeout determines how long the server will keep the session active without receiving any requests or heartbeats from the client. Once the timeout expires, the session is terminated, it may not be reopened and any ephemeral znodes created under it are automatically deleted.

- Heartbeats

- In ZooKeeper, each client session has a timeout. To prevent the server from thinking the client is dead, the client periodically sends heartbeats—small messages that indicate it is still alive—even when no other requests are being made. The interval between heartbeats is set short enough so that:

- If a server fails, the client detects it quickly (through a read timeout).

- The client can reconnect to another server in the ensemble before the session timeout expires, keeping the session active.

- Without heartbeats, the server might expire the session, deleting any ephemeral znodes tied to it. So heartbeats are essential to maintain session liveness during idle periods.

- And although the session is tracked by the server, ZooKeeper’s design allows the session state to be transferred to another server: when the client connects to a new server, the ensemble ensures that the new server resumes the same session with all associated ephemeral znodes and watches intact. This mechanism allows the client to maintain a consistent session across server failures or reboots, keeping ephemeral nodes alive as long as the session timeout is not exceeded.

- In ZooKeeper, each client session has a timeout. To prevent the server from thinking the client is dead, the client periodically sends heartbeats—small messages that indicate it is still alive—even when no other requests are being made. The interval between heartbeats is set short enough so that:

- Failover

- Failover to another ZooKeeper server is handled automatically by the ZooKeeper client.

- Sessions (and associated ephemeral znodes) are still valid after another server takes over from the failed one.

- During failover, the application will receive notifications of disconnections and connections to the service.

- Watch notifications will not be delivered while the client is disconnected, but they will be delivered when the client successfully reconnects.

- If the application tries to perform an operation while the client is reconnecting to another server, the operation will fail.

- Time

- There are several time parameters in ZooKeeper.

- The tick time is the fundamental period of time in ZooKeeper and is used by servers in the ensemble to define the schedule on which their interactions run. Other settings are defined in terms of tick time or constrained by it.

- A common tick time setting is 2 seconds.

- Example: the session timeout can only be configured between 2~20 ticks (i.e., 4~40 seconds).

- The tick time in ZooKeeper is configurable, not fixed. Administrators can tune tick time based on the deployment’s latency and performance requirements.

- States

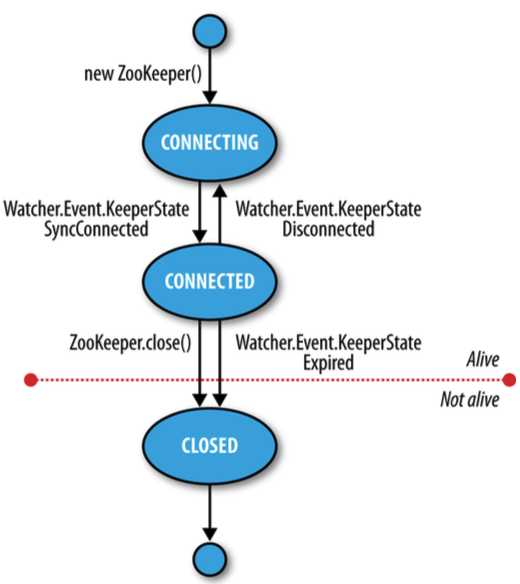

- In ZooKeeper, a client’s ZooKeeper object goes through different states during its lifecycle, such as connecting, connected, disconnected, or expired. You can query the current state at any time using the getState() method.

- Additionally, clients can register a Watcher to receive notifications whenever the state changes, allowing the application to respond to events like connection loss, reconnection, or session expiration.

Building applications with ZooKeeper

Group membership

- ZooKeeper can be used to implement group membership for distributed services, allowing clients to locate active servers reliably. To maintain the membership list without a single point of failure, ZooKeeper uses znodes: a parent znode represents the group, and child znodes represent individual members. To create a group, a znode (e.g., /zoo) is created for the group itself. Servers join the group by creating ephemeral child znodes, which automatically disappear if the server fails or exits, ensuring the membership list reflects the current active members. Clients can list all members using the getChildren() method on the parent znode. Deleting a group requires first removing all child znodes, since ZooKeeper does not support recursive deletion; the delete() method is used, and specifying -1 for the version bypasses version checks. This approach provides an active, fault-tolerant membership list that dynamically updates as servers join or leave.

Configuration service

- ZooKeeper can serve as a highly available configuration service for distributed applications, enabling machines in a cluster to share common configuration data. At a basic level, it stores configuration as key-value pairs, where the keys are represented by znode paths and the values are strings. Clients can retrieve or update this data, and using watches, interested clients can be notified automatically when configuration changes occur, creating an active configuration service. This model often assumes a single client performs updates at a time—for example, a master node like the HDFS NameNode updating information that worker nodes need—ensuring consistent and up-to-date configuration across the cluster.

Lock service

- ZooKeeper provides a robust distributed lock service, which is essential for coordinating access to shared resources in a distributed system. A distributed lock ensures mutual exclusion, meaning that at any given time, only one client can hold the lock. To implement this, a lock znode is designated, for example /leader, representing the lock on a resource. Clients that wish to acquire the lock create ephemeral sequential child znodes under this parent znode. ZooKeeper assigns a unique, monotonically increasing sequence number to each child znode, providing a total ordering among clients. The client whose znode has the lowest sequence number is considered the current lock holder. Ephemeral znodes ensure automatic cleanup in case a client crashes, releasing the lock for the next contender without manual intervention.

- When multiple clients contend for the lock, efficient notification is crucial to avoid overloading the ZooKeeper ensemble. In a naïve approach, all clients watch the lock znode for changes in its children. However, this leads to the herd effect, where thousands of clients are notified of changes even though only one can acquire the lock at a time, creating traffic spikes and performance bottlenecks. ZooKeeper avoids this by having each waiting client set a watch only on the znode immediately preceding its own in sequence (i.e., the znode with the previous sequence number). For example, if the lock znodes are /leader/lock-1, /leader/lock-2, and /leader/lock-3, the client for lock-3 watches only lock-2. When lock-2 is deleted, the client for lock-3 is notified and can acquire the lock. This selective notification ensures that only the next contender is alerted, reducing unnecessary traffic and preventing the herd effect while maintaining correct lock ordering.

- The lock acquisition process works as follows: a client creates its ephemeral sequential znode, retrieves the list of children under the lock znode, and checks if its znode has the lowest sequence number. If it does, the lock is acquired. If not, the client sets a watch on the znode immediately preceding its own and waits. When that znode is deleted, the client is notified, repeats the check, and acquires the lock if it now has the lowest sequence number. This process guarantees deterministic ordering among clients while maintaining fairness in lock acquisition.

- Lock release and failover are automatic and reliable due to ephemeral znodes. When the lock-holding client deletes its znode—or if the client crashes, causing ZooKeeper to remove the ephemeral znode—the next client in sequence is notified and acquires the lock. This mechanism ensures automatic failover without manual intervention. The combination of sequential numbering and ephemeral znodes allows the system to handle client crashes gracefully while maintaining strict mutual exclusion.

- Overall, ZooKeeper’s distributed lock service leverages ephemeral sequential znodes, watches on immediate predecessors, and deterministic ordering to provide a scalable, fault-tolerant, and efficient locking mechanism. It avoids unnecessary notifications, supports automatic failover, and guarantees that locks are acquired fairly among contending clients. This design makes it ideal for building higher-level coordination services, such as leader election, configuration management, and other distributed synchronization tasks in large-scale systems.

Doubts:

- Q: How is a leader elected in ZooKeeper?

-

A: ZooKeeper elects a leader to coordinate write operations and maintain consistency across the ensemble. When servers start, each enters the LOOKING state and proposes a leader candidate, typically based on the highest transaction ID (zxid) or server ID. Servers exchange votes, and a candidate becomes leader once it receives a majority of votes. The elected leader transitions to the LEADING state, while others become FOLLOWERS. If the leader fails, the remaining servers automatically re-enter the election process. This election uses the Zab (ZooKeeper Atomic Broadcast) protocol to ensure the chosen leader is consistent and preserves all committed transactions.

- Q: Why is there no full consensus needed in ZooKeeper’s ephemeral sequential znode leader election?

- A: In ephemeral sequential znode leader election, a full consensus protocol is not needed because ZooKeeper itself guarantees atomic and ordered creation of sequential znodes. Each server creates a znode with a unique increasing sequence number, and the leader is deterministically chosen as the server with the smallest sequence number. Since all servers can independently see the same sequence order, there are no conflicting proposals and no ambiguity in leader selection. Consensus protocols like Zab are still required for replicating write transactions, but leader election leverages ZooKeeper’s built-in ordering guarantees, making the process coordination-free and deterministic.