The Dual Problem of SVM

In machine learning, optimization problems often present themselves as key challenges. For example, when training a Support Vector Machine (SVM), we are tasked with finding the optimal hyperplane that separates two classes in a high-dimensional feature space. While we can solve this directly using methods like subgradient descent, we can also leverage a more analytical approach through Quadratic Programming (QP) solvers.

Moreover, for convex optimization problems, there is a powerful technique known as solving the dual problem. Understanding this duality is not only essential for theory, but it also offers computational advantages. In this blog, we’ll dive into the dual formulation of SVM and its implications.

SVM as a Quadratic Program

To understand the dual problem of SVM, let’s first revisit the primal optimization problem for SVMs. The goal of an SVM is to find the hyperplane that maximizes the margin between two classes. The optimization problem can be written as:

\[\begin{aligned} \min_{w, b, \xi} \quad & \frac{1}{2} \|w\|^2 + C \sum_{i=1}^n \xi_i \\ \text{subject to} \quad & -\xi_i \leq 0 \quad \text{for } i = 1, \dots, n, \\ & 1 - y_i (w^T x_i + b) - \xi_i \leq 0 \quad \text{for } i = 1, \dots, n, \end{aligned}\]Primal—sounds technical, right? Here’s what it means: The primal problem refers to the original formulation of the optimization problem in terms of the decision variables (in this case, \(w\), \(b\), and \(\xi\)) and the objective function. It is called “primal” because it directly represents the problem without transformation. The primal form of SVM is concerned with finding the optimal hyperplane parameters that minimize the classification error while balancing the margin size.

Breakdown of the Problem

-

Objective Function: The term \(\frac{1}{2} \|w\|^2\) is a regularization term that aims to minimize the complexity of the model, ensuring that the hyperplane is as “wide” as possible. The second term, \(C \sum_{i=1}^n \xi_i\), penalizes the violations of the margin (through slack variables \(\xi_i\)) and controls the trade-off between margin size and misclassification.

-

Constraints: The constraints consist of two parts:

- The first part ensures that slack variables are non-negative: \(-\xi_i \leq 0\), meaning that each slack variable must be at least zero. Why? The slack variables represent the margin violations, and they must be non-negative because they quantify how much a data point violates the margin, which cannot be negative.

- The second part enforces that the data points are correctly classified or their margin violations are captured by \(\xi_i\). For each data point \(i\), the condition \(1 - y_i (w^T x_i + b) - \xi_i \leq 0\) must hold. Here, \(y_i\) is the true label of the data point, and \(w^T x_i + b\) represents the signed distance of the point from the hyperplane. If the point is correctly classified and lies outside the margin (i.e., its signed distance from the hyperplane is greater than 1), the constraint holds true. If the point is misclassified or falls inside the margin, the slack variable \(\xi_i\) will account for this violation.

This problem has a differentiable objective function, affine constraints, and includes a number of unknowns that can be solved using Quadratic Programming (QP) solvers.

So, Quadratic Programming (QP) is an optimization problem where the objective function is quadratic (i.e., includes squared terms like \(\|w\|^2\)), and the constraints are linear. In the context of SVM, QP is utilized because the objective function involves the squared norm of \(w\) (which is quadratic), and the constraints are linear inequalities.

The QP formulation for SVM involves minimizing a quadratic objective function (with respect to \(w\), \(b\), and \(\xi\)) subject to linear constraints. Now, while QP solvers provide an efficient way to tackle this problem, let’s explore the dual problem(next) to gain further insights.

But, why bother with the dual problem? Here’s why it’s worth the dive:

-

Efficient Computation with Kernels: The dual formulation focuses on Lagrange multipliers and inner products between data points, rather than directly optimizing \(w\) and \(b\). This is particularly beneficial when using kernels, as it avoids explicit computation in high-dimensional spaces. For non-linear problems or datasets where relationships are better captured in transformed spaces, the dual approach enables efficient computation while leveraging the kernel trick.

-

Geometrical Insights: The dual formulation emphasizes the relationship between support vectors and the margin, offering a clearer geometrical interpretation. It shows that only the support vectors (the points closest to the decision boundary) determine the optimal hyperplane.

-

Convexity and Global Optimality: The dual problem is convex, ensuring that solving it leads to the global optimal solution. This is particularly beneficial when the primal problem has a large number of variables and constraints.

In short, while QP solvers can efficiently solve the primal problem, the dual problem formulation offers computational benefits, the potential for kernel methods, and a clearer understanding of the SVM model’s properties. This makes the dual approach a powerful tool in SVM optimization.

No need to worry about the details above—we’ll cover them step by step. For now, keep reading!

The Lagrangian

To begin understanding the dual problem, we need to define the Lagrangian of the optimization problem. For general inequality-constrained optimization problems, the goal is:

\[\begin{aligned} \min_x \quad & f_0(x) \\ \text{subject to} \quad & f_i(x) \leq 0, \quad i = 1, \dots, m. \end{aligned}\]The corresponding Lagrangian is defined as:

\[L(x, \lambda) = f_0(x) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i f_i(x),\]where:

- \(\lambda_i\) are the Lagrange multipliers (also known as dual variables).

- The Lagrangian function combines the objective function \(f_0(x)\) with the constraints \(f_i(x)\), weighted by the Lagrange multipliers \(\lambda_i\). These multipliers represent how much the objective function will change if we relax or tighten the corresponding constraint.

Why Do We Use the Lagrangian?

The Lagrangian serves as a bridge between constrained and unconstrained optimization. Here’s the intuition behind its design and necessity:

- Softening Hard Constraints:

- In constrained optimization, the solution must strictly satisfy all constraints, which can make direct optimization challenging.

- By introducing Lagrange multipliers, the constraints are “softened” into penalties. This means that instead of strictly enforcing constraints during every step of optimization, we penalize deviations from the constraints in the objective function.

- Unified Objective:

- The Lagrangian integrates the objective function and constraints into a single function. This allows us to handle both aspects of the problem (maximizing or minimizing while respecting constraints) in one unified framework.

- Flexibility:

- The Lagrange multipliers \(\lambda_i\) provide a mechanism to adjust the influence of each constraint. If a constraint is more critical, its corresponding multiplier will have a larger value, increasing its contribution to the Lagrangian.

- Theoretical Insights:

- The Lagrangian formulation is foundational to deriving the dual problem, which can sometimes simplify the original (primal) problem. It also provides deeper insights into the sensitivity of the solution to changes in the constraints.

Think of it this way:

Imagine you’re managing a budget to purchase items for a project. Your primary goal is to minimize costs (the objective function), but you have constraints like a maximum budget and a minimum quality requirement for each item.

- Without the Lagrangian: You’d need to find solutions that satisfy the budget and quality constraints explicitly, which could be cumbersome.

- With the Lagrangian: You assign a penalty (via Lagrange multipliers) to every dollar you overspend or every unit of quality you fail to meet. Now, your goal is to minimize the combined cost (original cost + penalties), which naturally leads you to solutions that respect the constraints.

In optimization terms, the Lagrangian lets us trade off between violating constraints and optimizing the objective function. This trade-off is critical in complex problems where perfect feasibility might not always be achievable during intermediate steps.

The Role of Lagrange Multipliers

The multipliers \(\lambda_i\) play a dual role:

-

They measure the sensitivity of the objective function to the corresponding constraint. For instance, if increasing the limit of a constraint by a small amount significantly improves the objective, its multiplier will have a large value.

-

They ensure that the optimal solution respects the constraints. If a constraint is not active at the solution (i.e., it is satisfied without being tight), its multiplier will be zero. This is formalized in the concept of complementary slackness, which we’ll explore later.

In essence, the Lagrangian is not just a mathematical tool; it reflects the natural balance between objectives and constraints, making it indispensable in optimization theory.

Lagrange Dual Function

Next, we define the Lagrange dual function, which plays a crucial role in deriving the dual problem. The dual function is obtained by minimizing the Lagrangian with respect to the primal variables (denoted as \(x\)):

\[g(\lambda) = \inf_x L(x, \lambda) = \inf_x \left[ f_0(x) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i f_i(x) \right].\]What Does This Mean?

The Lagrange dual function \(g(\lambda)\) gives us the smallest possible value of the Lagrangian \(L(x, \lambda)\) for a given set of Lagrange multipliers \(\lambda_i \geq 0\). It represents the “best” value of the Lagrangian when we optimize over the primal variables \(x\).

In simpler terms:

- The primal variables \(x\) are those we’re directly trying to optimize in the original problem.

- By minimizing over \(x\) for fixed \(\lambda\), we explore how well the Lagrangian balances the objective function \(f_0(x)\) and the weighted constraints \(f_i(x)\).

Why Do We Minimize Over \(x\)?

The reason for this step is that it helps us decouple the influence of the primal variables \(x\) and the dual variables \(\lambda\). By focusing only on \(x\), we shift our attention to understanding the properties of the dual variables, which simplifies the problem and provides valuable insights.

Minimizing the Lagrangian with respect to \(x\) ensures that:

- Feasibility of Constraints:

- The minimization respects the constraints \(f_i(x) \leq 0\) through the penalization mechanism introduced by \(\lambda_i\).

- Dual Representation:

- The dual function \(g(\lambda)\) captures how “good” a particular choice of \(\lambda\) is in approximating the original problem.

- Foundation for the Dual Problem:

- The minimization step builds the foundation for solving the optimization problem via its dual formulation, which is often simpler than the primal.

Why Do We Need This?

The goal of introducing the dual function is to exploit the following properties, which help us solve the original optimization problem more efficiently:

-

Lower Bound Property: The dual function \(g(\lambda)\) provides a lower bound on the optimal value of the primal problem. If \(p^*\) is the optimal value of the primal problem, then: \(g(\lambda) \leq p^*, \quad \forall \lambda \geq 0.\) This property is useful because even if we cannot solve the primal problem directly, we can approximate its solution by maximizing \(g(\lambda)\).

-

Convexity of \(g(\lambda)\): The dual function is always concave, regardless of whether the primal problem is convex. This makes the dual problem easier to solve using convex optimization techniques.

How Does This Work? Why Does It Work?

- Lower Bound Property:

- When we minimize the Lagrangian \(L(x, \lambda)\) with respect to the primal variables \(x\), we’re essentially finding the “best possible value” of the objective function \(f_0(x)\) for a fixed choice of \(\lambda\).

- Since the dual function \(g(\lambda)\) is derived from a relaxed version of the primal problem (allowing \(\lambda_i \geq 0\) to penalize constraint violations), it cannot exceed the true optimal value \(p^*\) of the primal problem. This creates the lower bound.

Intuition: Think of the dual function as a “proxy” for the primal problem. By maximizing \(g(\lambda)\), we try to approach the primal solution as closely as possible from below.

- Convexity of \(g(\lambda)\):

- The concavity of \(g(\lambda)\) follows from its definition as the infimum (or greatest lower bound) of a family of affine functions. In optimization, operations involving infima tend to preserve convexity (or result in concavity for maximization problems).

- This property ensures that maximizing \(g(\lambda)\) is computationally efficient, even if the original primal problem is non-convex.

Intuition: The concave structure of \(g(\lambda)\) creates an inverted “bowl-shaped” surface, making it easier to find the maximum using gradient-based optimization methods.

What is \(\inf\) and How is it Different from \(\min\)?

The infimum (denoted as \(\inf\)) is a generalization of the minimum (\(\min\)) in optimization and analysis. Here’s the distinction:

- Minimum (\(\min\)):

- The minimum is the smallest value attained by a function within its domain. It must be achieved by some point \(x\) in the domain.

- Example: For \(f(x) = x^2\) on \([0, 2]\), the minimum is \(f(0) = 0\).

- Infimum (\(\inf\)):

- The infimum is the greatest lower bound of a function, but it may not be attained by any point in the domain. It represents the “smallest possible value” the function can approach, even if it doesn’t reach it.

- Example: For \(f(x) = 1/x\) on \((0, 2]\), the infimum is \(\inf f(x) = 0\), but \(f(x)\) never actually equals \(0\) within the domain.

Why Use \(\inf\) Instead of \(\min\)?

In the context of the dual function:

- The infimum \(\inf_x L(x, \lambda)\) is used because the Lagrangian \(L(x, \lambda)\) might not achieve a true minimum for certain values of \(\lambda\) (e.g., the domain could be open or unbounded).

- Using \(\inf\) ensures that the dual function \(g(\lambda)\) is well-defined, even in cases where \(\min_x L(x, \lambda)\) doesn’t exist.

A Lighter Take

Think of this as “playing with math language” to get to the result we want. Just as you might rephrase a sentence to make it clearer or more persuasive, in mathematics, we transform the problem into a new form (the dual) that’s easier to work with.

For now, trust the process. This step might seem abstract, but it leads us to a form of the problem where powerful mathematical tools can come into play. Once we see the bigger picture, the reasoning behind these transformations will become clear.

In essence, the Lagrange dual function \(g(\lambda)\) gives us a way to shift our perspective on the optimization problem, helping us solve it through duality principles. As we proceed, you’ll see how this approach simplifies the original problem and why it’s such a powerful concept.

The Primal and the Dual

For any general primal optimization problem:

\[\begin{aligned} \min_x \quad & f_0(x) \\ \text{subject to} \quad & f_i(x) \leq 0, \quad i = 1, \dots, m, \end{aligned}\]we can formulate the corresponding dual problem as:

\[\begin{aligned} \max_\lambda \quad & g(\lambda) \\ \text{subject to} \quad & \lambda_i \geq 0, \quad i = 1, \dots, m. \end{aligned}\]The dual problem has some remarkable properties:

- Convexity: The dual problem is always a convex optimization problem, even if the primal problem is not convex.

- Simplification: In some cases, solving the dual problem is easier than solving the primal problem directly. This is particularly true when the primal problem is difficult to solve or the number of constraints is large.

Contract Negotiation Analogy

-

Primal Problem (Your Terms): Think of the primal problem as negotiating a contract where you aim to minimize costs while respecting certain constraints (like budget or timelines). You’re focused on getting the best deal for yourself under these limitations.

-

Lagrangian (Penalties for Violations): During the negotiation, you introduce penalties — if you can’t meet a certain term, you adjust other aspects of the contract. This is similar to using Lagrange multipliers in the Lagrangian function to penalize constraint violations.

-

Dual Problem (Value Assessment): In the dual problem, you step into the other party’s shoes and assess how much value they assign to the contract’s terms, maximizing the value they place on the constraints (such as how much they’d pay for more time or resources).

-

Duality: The primal (minimizing costs) and dual (maximizing value) problems balance each other. Weak duality means the dual value is a lower bound to the primal, and strong duality means the best deal is the same for both sides when the optimal values align.

Below are the next two important results derived from the above formulation.

Weak and Strong Duality

-

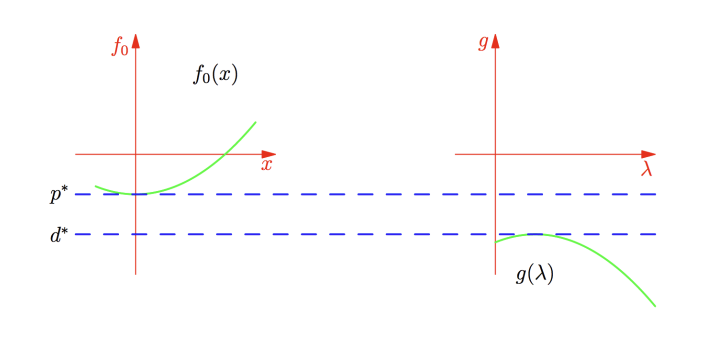

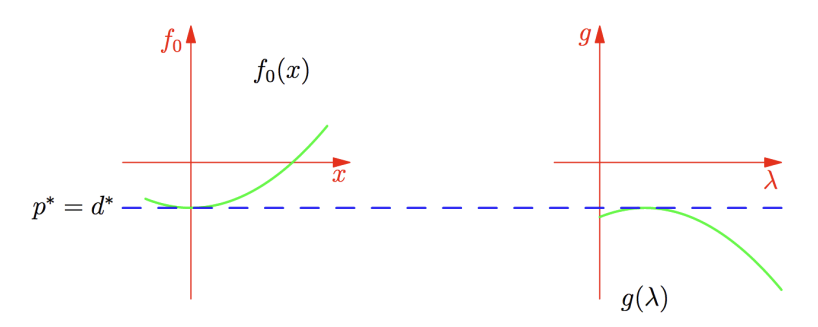

Weak Duality: This property tells us that the optimal value of the primal problem is always greater than or equal to the optimal value of the dual problem:

\[p^* \geq d^*,\]where \(p^*\) and \(d^*\) are the optimal values of the primal and dual problems, respectively. This is a fundamental result in optimization theory. Why so? Because the dual problem is designed to provide a lower bound on the primal objective through the Lagrangian.

-

Strong Duality: In some special cases (such as when the problem satisfies Slater’s condition), strong duality holds, meaning the optimal values of the primal and dual problems are equal:

\[p^* = d^*.\]Strong duality is particularly useful because it allows us to solve the dual problem instead of the primal one, often simplifying the problem or reducing computational complexity.

Slater’s Conditions

- They are a set of conditions that guarantee strong duality in certain types of constrained optimization problems (particularly convex problems).

- They state that for strong duality to hold, there must exist a strictly feasible point (a point where all inequality constraints are strictly satisfied).

- In simpler terms, Slater’s conditions ensure that there is at least one point where all the constraints are strictly satisfied, which enables strong duality and ensures that the primal and dual solutions align.

- These conditions are crucial in convex optimization as they help guarantee the optimal solutions for both the primal and dual problems are the same.

Complementary Slackness

When strong duality holds, we can derive the complementary slackness condition. This condition provides deeper insight into the relationship between the primal and dual solutions. Specifically, if \(x^*\) is the optimal primal solution and \(\lambda^*\) is the optimal dual solution, we have:

\[f_0(x^*) = g(\lambda^*) = \inf_x L(x, \lambda^*) \leq L(x^*, \lambda^*) = f_0(x^*) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^* f_i(x^*).\]For this equality to hold, the term \(\sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^* f_i(x^*)\) must be zero for each constraint. This leads to the following complementary slackness condition:

- If \(\lambda_i^* > 0\), then \(f_i(x^*) = 0\), meaning that the corresponding constraint is active at the optimal point. Also, it means the constraint is tight and directly affects the optimal solution.

- If \(f_i(x^*) < 0\), then \(\lambda_i^* = 0\), meaning that the corresponding constraint is inactive. This indicates that the constraint doesn’t influence the optimal solution at all.

This condition tells us which constraints are binding (active) at the optimal solution and which are not, providing critical information about the structure of the optimal solution.

Contract Negotiation Analogy: Duality and Complementary Slackness

Strong Duality and Weak Duality:

-

Weak Duality: In a contract negotiation, weak duality is like the minimum acceptable price for the other party. The price (dual value) they would accept for your offer will always be a lower bound to what you are willing to pay (primal cost). The other party cannot ask for more than what you’re offering, but they may accept less.

-

Strong Duality: Strong duality happens when both parties agree on the same optimal terms for the contract. Both your best offer (primal) and the value assigned to the terms (dual) align perfectly, resulting in the best possible contract for both sides.

Complementary Slackness:

- Complementary Slackness tells us which terms of the contract are really influencing the negotiation outcome.

- If a dual variable (e.g., the price or terms the other party values) is positive, then the corresponding primal constraint (e.g., a term you care about, like the delivery time or cost) is active — it must be part of the final agreement.

- If a primal constraint (e.g., a timeline or budget) is not strict enough (it’s not a deal-breaker), then the dual variable (e.g., the value the other party assigns to it) is zero, meaning it doesn’t impact the outcome.

Example:

- Suppose you’re negotiating a project deadline. If the other party values the deadline highly (dual value is positive), it must be part of the contract (the deadline is active). If they don’t care much about it, then it doesn’t matter to the final deal (dual value is zero), and you can relax that constraint.

Finally, there might be one question left—this is the one I had, so here’s the explanation:

If the Lagrangian dual function is concave, how is the Lagrangian dual problem always a convex optimization problem?

To understand why the dual problem is always a convex optimization problem, let’s revisit its structure: \(\max_{\lambda \geq 0} \; g(\lambda).\)

-

Maximizing a Concave Function:

The dual function \(g(\lambda)\) is concave by construction. In optimization, maximizing a concave function is equivalent to minimizing a convex function (negating the objective). Therefore, the objective of the dual problem aligns with the structure of a convex optimization problem. -

Convex Feasible Region:

The constraints in the dual problem (\(\lambda \geq 0\)) define a convex set, as the non-negative orthant in \(\mathbb{R}^m\) is convex.

Definition of a Convex Optimization Problem:

A problem is a convex optimization problem if:

- The objective function is convex (for minimization) or concave (for maximization).

- The feasible region is a convex set.

The dual problem satisfies these conditions because:

- The objective function \(g(\lambda)\) is concave.

- The constraint \(\lambda \geq 0\) defines a convex feasible region.

Thus, the dual problem is always a convex optimization problem, regardless of whether the primal problem is convex or not.

Intuition Behind Convexity of the Dual Problem

The dual problem’s convexity comes from the way it is constructed:

- The Lagrangian combines the primal objective and constraints into a single function that penalizes constraint violations.

- By minimizing the Lagrangian over the primal variables \(x\), the dual function \(g(\lambda)\) captures the tightest lower bound of the primal objective.

- The pointwise infimum of affine functions (as in \(g(\lambda)\)) is guaranteed to be concave.

- The dual problem maximizes this concave function over a convex set (\(\lambda \geq 0\)), making it a convex optimization problem.

This ensures that solving the dual problem is computationally efficient and well-structured, even when the primal problem is non-convex.

Conclusion

By exploring the dual problem of SVM, we gain both theoretical insights and practical benefits. The dual formulation provides a new perspective on the original optimization problem, and solving it can sometimes be more efficient or insightful. The duality between the primal and dual problems underpins many of the optimization techniques used in machine learning, particularly in the context of support vector machines.

Pat yourselves on the back for making it to the end of this blog! Take a well-deserved break, and stay tuned for the next one, where we’ll apply everything we’ve learned so far to formulate the SVM dual problem.