Unleashing the Power of Linear Models - Tackling Nonlinearity with Feature Maps

Understanding the Input Space \(\mathcal{X}\)

In machine learning, the input data we work with often originates from domains far removed from the mathematical structures we typically rely on. Text documents, image files, sound recordings, and even DNA sequences all serve as examples of such diverse input spaces. While these data types can be represented numerically, their raw form often lacks the structure necessary for effective analysis.

Consider text data: each sequence might consist of words or characters, but the numerical representation of one text sequence may not align with another. The \(i\)-th entry of one sequence might hold a different meaning compared to the same position in another. Moreover, sequences like these often vary in length, which makes it even more challenging to align them into a consistent numerical format.

This lack of structure highlights a fundamental challenge: we need a way to standardize and represent inputs in a meaningful way. The solution lies in a process called feature extraction.

Feature Extraction: Bridging the Gap Between Input and Model

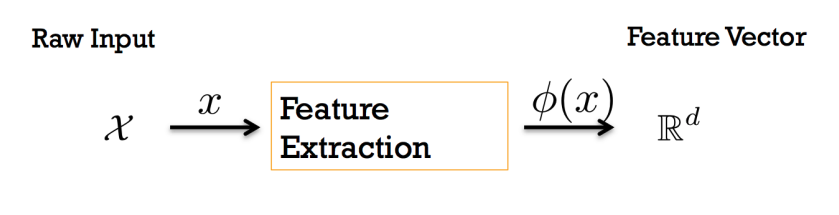

Feature extraction, also known as featurization, is the process of transforming inputs from their raw forms into structured numerical vectors that can be processed by machine learning models. Think of it as translating the data into a language that models can understand and interpret.

Mathematically, we define feature extraction as a mapping: \(\phi: \mathcal{X} \to \mathbb{R}^d\) Here, \(\phi(x)\) takes an input \(x\) from the space \(\mathcal{X}\) and maps it into a \(d\)-dimensional vector in \(\mathbb{R}^d\). This transformation is crucial because it creates a consistent numerical structure that machine learning algorithms require.

Linear Models and Explicit Feature Maps

Let’s delve into how feature extraction integrates with linear models. In this setup, we make no assumptions about the input space \(\mathcal{X}\). Instead, we introduce a feature map: \(\phi: \mathcal{X} \to \mathbb{R}^d\)

This feature map transforms inputs into a feature space \(\mathbb{R}^d\), enabling the use of standard linear model frameworks. Once in the feature space, the hypothesis space of affine functions is defined as:

\[F = \left\{ x \mapsto w^T \phi(x) + b \mid w \in \mathbb{R}^d, \, b \in \mathbb{R} \right\}\]In this formulation:

- \(w\) represents the weights assigned to each feature.

- \(b\) is the bias term.

- \(\phi(x)\) is the feature-transformed representation of the input.

This approach allows linear models to leverage the structured feature space effectively.

Geometric Intuition: Solving Nonlinear Problems with Featurization

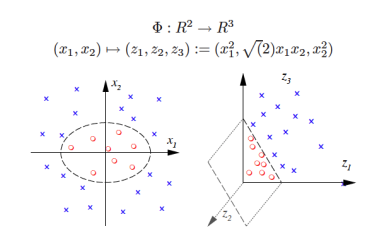

Imagine a two-class classification problem where the decision boundary is nonlinear. Using the identity feature map \(\phi(x) = (x_1, x_2)\), a linear model fails because the data points cannot be separated by a straight line in the original input space.

However, by applying an appropriate feature map, such as: \(\phi(x) = (x_1, x_2, x_1^2 + x_2^2)\) we can transform the data into a higher-dimensional space. In this transformed space, the previously nonlinear boundary becomes linearly separable.

This geometric perspective is a powerful way to understand how feature maps enhance the capability of machine learning models. If you’d like to visualize this concept, consider watching this illustrative video.

Expanding the Hypothesis Space: The Role of Features

The expressivity of a linear model—its ability to capture complex relationships—depends directly on the features it has access to. To increase the hypothesis space’s expressivity, we must introduce additional features.

For instance, moving from basic linear features to polynomial or interaction features enables the model to capture more intricate patterns in the data. This expanded hypothesis space is often described as more expressive because it can fit a broader range of input-output relationships.

However, with great expressivity comes the challenge of ensuring these features are meaningful and contribute to the task at hand. The art of feature design lies in striking the right balance: creating features that enhance the model’s capacity without overfitting or adding noise.

Handling Nonlinearity with Linear Methods

In machine learning, linear models are often preferred for their simplicity, interpretability, and efficiency. However, real-world problems rarely exhibit purely linear relationships, and this is where the challenge arises. How can we handle nonlinearity while retaining the advantages of linear methods?

Let’s take an example task: predicting an individual’s health score. At first glance, this might seem straightforward—after all, we can list plenty of features relevant to medical diagnosis, such as:

- Height

- Weight

- Body temperature

- Blood pressure

While these features are clearly useful, their relationships with the health score may not be linear. Furthermore, complex dependencies among these features can make predictions challenging. To address this, we must carefully consider the nature of nonlinearity and how it affects linear predictors.

Nonlinearities in data can broadly be categorized into three types:

- Non-monotonicity: When the relationship between a feature and the label does not follow a single increasing or decreasing trend.

- Saturation: When the effect of a feature diminishes beyond a certain point, despite continuing to grow.

- Interactions: When the effect of one feature depends on the value of another.

Each of these presents unique challenges for linear models. Let’s explore them in detail.

Non-monotonicity: When Extremes Behave Differently

Imagine we want to predict a health score \(y\) (where higher is better) based on body temperature \(t\). A simple feature map \(\phi(x) = [1, t(x)]\) assumes an affine relationship between temperature and health, meaning it can only model cases where:

- Higher temperatures are better, or

- Lower temperatures are better.

But in reality, both extremes of temperature are harmful, and health is best around a “normal” temperature (e.g., 37°C). This non-monotonic relationship poses a problem.

Solution 1: Domain Knowledge

One approach is to manually transform the input to account for the non-monotonicity. For instance: \(\phi(x) = \left[1, \left(t(x) - 37\right)^2 \right]\) Here, we explicitly encode the deviation from normal temperature. While effective, this solution relies heavily on domain knowledge and manual feature engineering.

Solution 2: Let the Model Decide

An alternative approach is to include additional features, such as: \(\phi(x) = \left[1, t(x), t(x)^2 \right]\) This makes the model more expressive, allowing it to learn the non-monotonic relationship directly from the data. As a general rule, features should be simple, modular building blocks that can adapt to various patterns.

Saturation: When Effects Diminish

Consider a recommendation system that scores products based on their relevance to a user query. One feature might be \(N(x)\), the number of people who purchased the product \(x\). Intuitively, relevance increases with \(N(x)\), but the relationship is not linear—beyond a certain point, each additional purchase contributes progressively less to relevance, reflecting diminishing returns.

The Solution:

To address saturation, we can apply nonlinear transformations to the feature. Two common methods are:

-

Smooth nonlinear transformation:

\[\phi(x) = [1, \log(1 + N(x))]\]The logarithm is particularly effective for features with large dynamic ranges, as it captures diminishing returns naturally.

-

Discretization:

\[\phi(x) = [1[0 \leq N(x) < 10], 1[10 \leq N(x) < 100], \ldots]\]By bucketing \(N(x)\) into intervals, this method provides flexibility while maintaining interpretability.

Interactions: When Features Work Together

Suppose we want to predict a health score based on a patient’s height \(h\) and weight \(w\). Using a feature map \(\phi(x) = [h(x), w(x)]\) assumes these features independently influence the outcome. However, it’s the relationship between height and weight (e.g., body mass index) that matters most.

Approach 1: Domain-Specific Features

One way to capture this interaction is to use domain knowledge, such as Robinson’s ideal weight formula: \(\text{weight(kg)} = 52 + 1.9 \cdot (\text{height(in)} - 60)\)

We can then score the deviation between actual weight \(w\) and ideal weight: \(f(x) = \left(52 + 1.9 \cdot [h(x) - 60] - w(x)\right)^2\)

While precise, this approach depends heavily on external knowledge and is less adaptable to other problems.

Approach 2: General Interaction Terms

A more flexible solution is to include all second-order features: \(\phi(x) = [1, h(x), w(x), h(x)^2, w(x)^2, h(x)w(x)]\) This approach eliminates the need for predefined formulas, letting the model discover relationships on its own. By using interaction terms like \(h(x)w(x)\), we can model complex dependencies in the data.

Monomial Interaction Terms: A Building Block for Nonlinearity

Interaction terms are fundamental for modeling nonlinearities. Starting with an input \(x = [1, x_1, \ldots, x_d]\), we can add monomials of degree \(M\), such as:

\[x_1^{p_1} \cdot x_2^{p_2} \cdots x_d^{p_d}, \quad \text{where } p_1 + \cdots + p_d = M\]For example, in a 2D space with \(M = 2\), the interaction terms would include \(x_1^2, x_2^2, \text{and } x_1x_2\).

Big Feature Spaces: Challenges and Solutions

Adding interaction terms and monomials rapidly increases the size of the feature space. For \(d = 40\) and \(M = 8\), the number of features grows to an astronomical \(314,457,495\). Such large feature spaces bring two major challenges:

- Overfitting: Addressed through regularization techniques like \(L1/L2\) penalties.

- Memory and Computational Costs: Kernel methods can help handle high (or infinite) dimensional spaces efficiently by computing feature interactions implicitly.

By leveraging feature maps and understanding the nuances of nonlinearities, we can significantly enhance the performance of linear models. In the next part, we’ll explore kernel methods and their role in handling complex feature spaces efficiently. Stay tuned, Bye 👋!