Gaussian Regression - A Bayesian Approach to Linear Regression

Gaussian regression provides a probabilistic perspective on linear regression, enabling us to model uncertainty in our predictions. Unlike traditional regression techniques that provide only point estimates, Gaussian regression models the entire distribution over possible predictions.

In this post, we will explore Gaussian regression through a step-by-step example in one dimension, gradually building intuition before moving to the Bayesian posterior update with multiple observations.

Gaussian Regression in One Dimension: Problem Setup

To understand Gaussian regression, let’s consider a simple one-dimensional regression task. Suppose our input space is:

\[X = [-1,1]\]and the output space is:

\[Y \subseteq \mathbb{R}\]We assume that for a given input \(x\), the corresponding output \(y\) is generated according to a linear model with additive Gaussian noise:

\[y = w_0 + w_1 x + \varepsilon, \quad \text{where} \quad \varepsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0, 0.2^2)\]In other words, the output is a linear function of \(x\) with coefficients \((w_0, w_1)\) and Gaussian noise \(\varepsilon\) with variance \(0.2^2\).

Alternatively, we can express this in probabilistic form as:

\[y \mid x, w_0, w_1 \sim \mathcal{N}(w_0 + w_1 x, 0.2^2)\]where the mean is given by the linear function \(w_0 + w_1 x\), and the variance captures the uncertainty in our observations.

Now, the question is: how do we model our belief about the parameters \(w_0\) and \(w_1\)?

Prior Distribution Over Parameters

Before observing any data, we assume a prior belief about the parameters \(w = (w_0, w_1)\). A common choice is to model the parameters as a zero-mean Gaussian distribution:

\[w = (w_0, w_1) \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \frac{1}{2} I)\]This prior reflects our initial assumption that \(w_0\) and \(w_1\) are likely to be small, centered around zero, with independent Gaussian uncertainty.

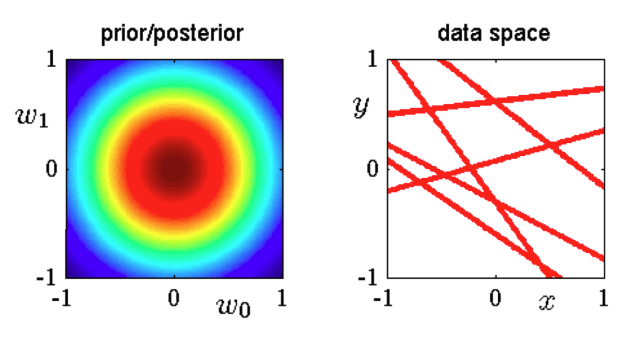

Visualizing the Prior

- The left plot below illustrates samples drawn from the prior distribution over \(w\).

- The right plot shows random linear functions \(y(x) = E[y \mid x, w] = w_0 + w_1 x\) drawn from this prior distribution \((w ∼ p(w))\).

Since no observations have been made yet, these functions represent potential hypotheses about the true relationship between \(x\) and \(y\).

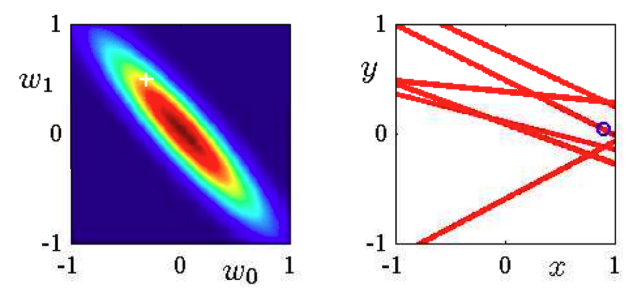

Updating Beliefs: Posterior After One Observation

Once we collect data, we can update our belief about \(w\) using Bayes’ theorem. Suppose we observe a single training point \((x_1, y_1)\).

This leads to a posterior distribution over \(w\), incorporating the evidence from our observation.

- The left plot below shows the updated posterior distribution over \(w\), where the white cross represents the true underlying parameters.

- The right plot now shows updated predictions based on this posterior. Blue circle indicates the training observation. The red lines represent sampled functions \(y(x) = E[y \mid x, w]\) drawn from the posterior \((w ∼ p(w \vert D) )\) instead of the prior.

Key Observations After One Data Point

- The posterior distribution is more concentrated, reflecting reduced uncertainty about \(w\).

- Predictions near the observed point \(x_1\) are more certain, while uncertainty remains high elsewhere.

Adding More Observations: Improved Predictions

Let’s now extend this idea by considering multiple observations.

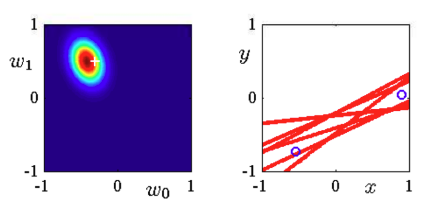

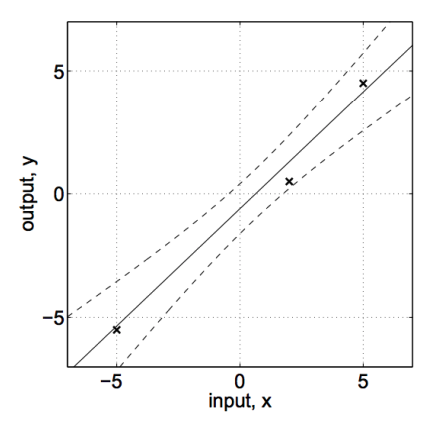

Posterior After Two Observations

- With two training points, the posterior further shrinks, indicating increased confidence in our estimate of \(w\).

- The red curves on the right become more aligned, meaning the model has more confidence in its predictions.

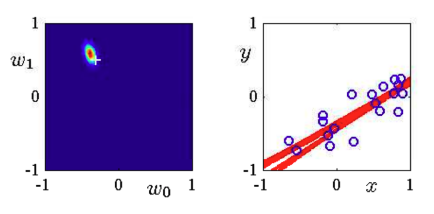

Posterior After Twenty Observations

- When we have twenty observations, our uncertainty about \(w\) significantly decreases.

- The predicted functions become highly concentrated, meaning the model has effectively learned the underlying relationship between \(x\) and \(y\).

This progression illustrates a fundamental principle in Bayesian regression: as we collect more data, the posterior distribution sharpens, leading to more confident predictions.

So, Gaussian regression provides a Bayesian approach to linear regression, allowing us to incorporate prior knowledge and update beliefs as new data arrives.

Key takeaways:

- We started with a prior distribution over parameters \(w\).

- We incorporated one observation, updating our belief using the posterior distribution.

- As we collected more data, our predictions became more confident, reducing uncertainty in our model.

This framework not only provides point predictions but also quantifies uncertainty, making it particularly useful for applications where knowing confidence levels is crucial.

Next up, we will derive the closed-form posterior distribution for Gaussian regression and explore its connection to ridge regression.

Deriving the General Posterior Distribution in Gaussian Regression

We begin by defining the prior belief about our parameters. Suppose we have a prior distribution over the weights:

\[w \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \Sigma_0)\]where \(\Sigma_0\) represents the prior covariance matrix, encoding our initial uncertainty about \(w\). Given an observed dataset \(D = \{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^{n}\), we assume the following likelihood model:

\[y_i \mid x_i, w \sim \mathcal{N}(w^T x_i, \sigma^2)\]where:

- \(X\) is the design matrix, consisting of all input feature vectors \(x_i\),

- \(y\) is the response column vector, representing the observed outputs,

- \(\sigma^2\) represents the variance of the noise in the observations.

Using Bayes’ theorem, we update our belief about \(w\) after observing data \(D\), leading to a Gaussian posterior distribution:

\[w \mid D \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_P, \Sigma_P)\]where the posterior mean \(\mu_P\) and covariance \(\Sigma_P\) are given by:

\[\mu_P = \left( X^T X + \sigma^2 \Sigma_0^{-1} \right)^{-1} X^T y\] \[\Sigma_P = \left( \sigma^{-2} X^T X + \Sigma_0^{-1} \right)^{-1}\]The posterior mean \(\mu_P\) provides the best estimate of \(w\) given the data, while the posterior covariance \(\Sigma_P\) captures the uncertainty in our estimation.

Maximum A Posteriori (MAP) Estimation and Its Connection to Ridge Regression

While the posterior distribution fully describes the uncertainty in \(w\), in practice, we often seek a point estimate. The MAP (Maximum A Posteriori) estimate of \(w\) is simply the posterior mean:

\[\hat{w} = \mu_P = \left( X^T X + \sigma^2 \Sigma_0^{-1} \right)^{-1} X^T y\]Now, let’s assume an isotropic prior variance:

\[\Sigma_0 = \frac{\sigma^2}{\lambda} I\]Plugging this into the MAP estimate simplifies it to:

\[\hat{w} = \left( X^T X + \lambda I \right)^{-1} X^T y\]which is precisely the ridge regression solution.

Thus, ridge regression can be interpreted as a Bayesian approach where we assume a Gaussian prior on the weights with variance controlled by \(\lambda\). The larger \(\lambda\), the stronger our prior belief that \(w\) should remain small, leading to regularization.

This is because the isotropic Gaussian prior on \(w\) has variance \(\frac{\sigma^2}{\lambda}\). As \(\lambda\) increases, the prior variance decreases, implying a stronger belief that the weights \(w\) are closer to zero (more regularization). This results in a simpler model with smaller coefficients, reducing overfitting by penalizing large weights.

Understanding the Posterior Density and Ridge Regression

To further illustrate the connection between MAP estimation and ridge regression, let’s look at the posterior density of \(w\) under the prior assumption \(\Sigma_0 = \frac{\sigma^2}{\lambda} I\):

\[p(w \mid D) \propto \underbrace{\exp \left( - \frac{\lambda}{2 \sigma^2} \|w\|^2 \right)}_{\text{Prior}} \underbrace{\prod_{i=1}^{n} \exp \left( - \frac{(y_i - w^T x_i)^2}{2 \sigma^2} \right)}_{\text{Likelihood}}\]To find the MAP estimate, we minimize the negative log-posterior:

\[\hat{w}_{\text{MAP}} = \arg\min_{w \in \mathbb{R}^d} \left[ -\log p(w \mid D) \right]\] \[\hat{w}_{\text{MAP}} = \arg\min_{w \in \mathbb{R}^d} \left[ \underbrace{\sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - w^T x_i)^2}_{\text{Log Likelihood}} + \underbrace{\lambda \|w\|^2}_{\text{Log Prior}} \right]\]This objective function is exactly the ridge regression loss function, which balances the data likelihood (sum of squared errors) with a penalty on the weight magnitude.

Thus, we see that MAP estimation in Bayesian regression is equivalent to ridge regression in frequentist statistics.

Predictive Posterior Distribution and Uncertainty Quantification

Now that we have obtained the posterior distribution of \(w\), we can compute the predictive distribution for a new input point \(x_{\text{new}}\). Instead of providing just a single point estimate, Bayesian regression gives a distribution over predictions, reflecting our confidence.

The predictive distribution is given by:

\[p(y_{\text{new}} \mid x_{\text{new}}, D) = \int p(y_{\text{new}} \mid x_{\text{new}}, w) p(w \mid D) dw\]Averages over prediction for each \(w\), weighted by posterior distribution.

The equation represents the predictive distribution for a new observation \(y_{\text{new}}\) given a new input \(x_{\text{new}}\) and the data \(D\).

It combines:

-

Likelihood \(p(y_{\text{new}} \mid x_{\text{new}}, w)\): This term describes how likely the new output \(y_{\text{new}}\) is for a given set of model weights \(w\) and the new input \(x_{\text{new}}\).

-

Posterior \(p(w \mid D)\): This is the distribution of the model weights \(w\) after observing the data \(D\), representing the uncertainty in the weights.

The integral averages the likelihood of the new observation over all possible values of the model parameters \(w\), weighted by the posterior distribution \(p(w \mid D)\), because we don’t know the exact value of \(w\) — it can vary based on the data \(D\).

Here’s why this happens:

-

Uncertainty in the weights: In Bayesian regression, we have uncertainty about the model parameters (weights) \(w\), and the posterior distribution \(p(w \mid D)\) reflects our belief about the possible values of \(w\), given the observed data \(D\).

-

Prediction is uncertain: For a new input \(x_{\text{new}}\), the prediction \(y_{\text{new}}\) depends on the model parameters \(w\), and since we have uncertainty in \(w\), we can’t give a single prediction. Instead, we need to compute the distribution over all possible values of \(y_{\text{new}}\) corresponding to all possible values of \(w\).

-

Integrating over the posterior: The integral averages over all possible values of \(w\) because we want to account for the uncertainty in \(w\), which is captured by the posterior distribution \(p(w \mid D)\). Each value of \(w\) contributes to the prediction \(y_{\text{new}}\) according to its likelihood, and the posterior distribution tells us how probable each \(w\) is. By integrating, we are essentially weighing each possible prediction by how likely the corresponding weight \(w\) is under the posterior distribution.

Thus, the integral provides the expected prediction by combining the likelihood of the new data with the uncertainty about the model parameters. This results in a distribution for the prediction, reflecting both the model’s uncertainty and the uncertainty in the new data.

Since both the likelihood and posterior are Gaussian, the predictive distribution is also Gaussian:

\[y_{\text{new}} \mid x_{\text{new}}, D \sim \mathcal{N} (\eta_{\text{new}}, \sigma_{\text{new}}^2)\]where:

\[\eta_{\text{new}} = \mu_P^T x_{\text{new}}\] \[\sigma_{\text{new}}^2 = x_{\text{new}}^T \Sigma_P x_{\text{new}} + \sigma^2\]The predictive variance \(\sigma_{\text{new}}^2\) consists of two terms:

- \(x_{\text{new}}^T \Sigma_P x_{\text{new}}\) – Uncertainty due to finite data, representing how much we should trust our estimate of \(w\) (or simply uncertainty from the variance of \(w\)).

- \(\sigma^2\) – Inherent observation noise, representing the irreducible error in predicting \(y\).

This decomposition highlights how Bayesian regression naturally incorporates uncertainty in predictions.

Why Bayesian Regression is Powerful

One major advantage of Bayesian regression over traditional point estimation methods is that it provides uncertainty estimates. So, With predictive distributions, we can give mean prediction with error bands.

This is particularly useful in applications where knowing confidence intervals is crucial, such as:

- Medical diagnostics, where uncertainty in predictions affects decision-making.

- Financial modeling, where risk estimation is key.

- Autonomous systems, where knowing when to be uncertain improves safety.

Conclusion

In this post, we derived the posterior distribution for Gaussian regression, connected MAP estimation to ridge regression, and explored the predictive posterior distribution, which quantifies uncertainty.

Bayesian regression provides a principled way to incorporate prior beliefs and quantify uncertainty, making it an essential tool in machine learning.

Next, we’ll take a brief pause from probabilistic machine learning methods, as we’ve covered the essentials thoroughly, and shift our focus to a new topic: Multiclass Classification. Stay tuned, and keep learning and growing!🚀