Gradient Boosting in Practice

In the previous post, we introduced Gradient Boosting with logistic loss, discussing how weak learners can be sequentially combined to minimize differentiable loss functions using functional gradient descent. Now, we turn our attention to how this elegant theory translates into robust, high-performing models in practice, particularly focusing on regularization techniques that help control overfitting and improve generalization.

Preventing Overfitting in Gradient Boosting

While gradient boosting is often surprisingly resistant to overfitting compared to other ensemble methods like bagging, it is not immune. Its resilience stems from several key characteristics of the boosting process:

-

Implicit Feature Selection:

One of the reasons gradient boosting is relatively resistant to overfitting is that it performs feature selection implicitly during training. At each boosting iteration, the algorithm fits a weak learner often a decision tree to the current pseudo-residuals (the gradients of the loss).Decision trees naturally perform feature selection: they evaluate all available features and choose the one that offers the best split (i.e., the greatest reduction in loss). This means that only the most predictive features are chosen at each step. Over multiple rounds, this leads to an ensemble that selectively and adaptively focuses on the most informative parts of the input space.

As a result, even in high-dimensional settings or with noisy features, gradient boosting can often avoid overfitting by not relying too heavily on irrelevant or redundant features. It prioritizes features that consistently contribute to reducing the loss, acting like a built-in greedy feature selection mechanism.

-

Localized Additive Updates:

In gradient boosting, each weak learner (such as a shallow decision tree) is trained to correct the mistakes of the current model. Because these learners are typically low-capacity (e.g., stumps or small trees), their predictions only affect specific regions of the input space - they’re “localized” in that sense.As boosting progresses, the model becomes more accurate, and the residuals (errors) it tries to fix get smaller and more focused. Consequently, the subsequent learners make increasingly smaller and more targeted updates. This means that instead of making large, sweeping changes to the model, later learners adjust predictions only in regions where the model is still wrong.

This gradual, fine-grained updating process helps avoid overfitting, as the model doesn’t overreact to noise or outliers - it incrementally improves where it matters most.

Together, these mechanisms help gradient boosting maintain a balance between flexibility and generalization. However, it can still overfit when models are overly complex or trained for too many iterations - which is why regularization techniques such as shrinkage, subsampling, and tree size constraints are essential in practice.

-

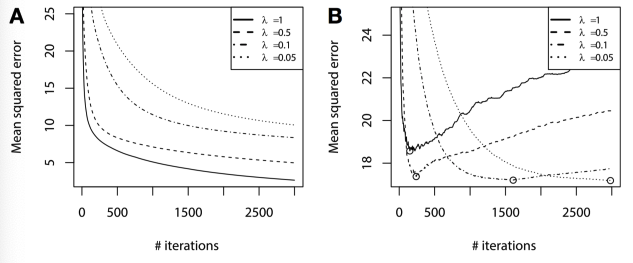

Shrinkage: Use a small learning rate (step size) \(\lambda\) to scale the contribution of each weak learner:

\[f_m(x) = f_{m-1}(x) + \lambda \cdot v_m h_m(x)\]Smaller \(\lambda\) slows down the learning process, often resulting in better generalization.

- Stochastic Gradient Boosting: Instead of using the full dataset at each boosting round, randomly sample a subset of training examples.

- Feature (Column) Subsampling: Randomly select a subset of input features for each boosting iteration.

These methods inject randomness into the learning process and reduce variance, both of which help mitigate overfitting.

Step Size as Regularization

One of the simplest and most effective ways to regularize gradient boosting is by adjusting the step size or learning rate. This directly controls how far the model moves in the direction of the negative gradient at each step. Smaller step sizes lead to slower learning, but allow the model to build more nuanced approximations of the target function.

This effect is clearly observed in tasks like Sinc function regression(which we saw in the last post - BinomialBoost), where the number of boosting rounds and the choice of shrinkage rate dramatically affect both training and validation performance. Lower learning rates typically result in better generalization when combined with more boosting rounds.

Stochastic Gradient Boosting

To improve efficiency and reduce overfitting, we can employ stochastic gradient boosting - a strategy analogous to minibatch gradient descent in optimization. So in minibatch, for each boosting round:

- Randomly sample a subset of the training data.

- Fit the base learner using this subset.

- Use it to approximate the gradient and update the model.

Benefits of this approach include:

- Regularization: Injecting randomness into the training process helps prevent overfitting.

- Efficiency: Training is faster per iteration since we work with fewer data points.

- Improved performance: Empirically, this often leads to better results for the same computational budget.

Column (Feature) Subsampling

Another effective technique borrowed from Random Forests is column or feature subsampling. For each boosting round:

- Randomly select a subset of input features.

- Learn a weak learner using only this subset.

This further reduces correlation between individual learners and acts as a strong regularizer. In fact, the XGBoost paper emphasizes that column subsampling can reduce overfitting even more effectively than row subsampling.

Additionally, limiting the number of features also improves training speed, especially for high-dimensional datasets.

Summary: Gradient Boosting as a Versatile Framework

Let’s step back and summarize the key takeaways:

- Motivation: Combine many weak learners (e.g., shallow trees) to build a strong predictor.

- Statistical view: Fit an additive model greedily, one function at a time.

- Optimization view: Boosting makes local improvement iteratively and perform gradient descent in function space.

Gradient Boosting is a flexible and powerful meta-algorithm:

- Supports any differentiable loss function

- Applicable to classification, regression, ranking, multiclass tasks, and more

- Highly scalable with implementations like XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost

With proper regularization, including shrinkage, stochastic updates, and feature subsampling - Gradient Boosting becomes one of the most effective tools in the machine learning toolkit.