Introduction to Gradient Boosting

In our previous discussions on ensemble methods, we explored boosting — a technique designed to reduce bias by combining several shallow decision trees, also known as weak learners. Each learner in the ensemble focuses on correcting the errors made by its predecessors. This iterative correction process results in a strong predictive model.

One prominent boosting method we covered was AdaBoost, a powerful off-the-shelf classifier. We touched on how AdaBoost operates by minimizing an exponential loss and adjusting the sample weights accordingly.

Now, let’s build on this foundation and transition into more general methods like Gradient Boosting, which extends the boosting idea to arbitrary differentiable loss functions.

From Nonlinear Regression to Gradient Boosting

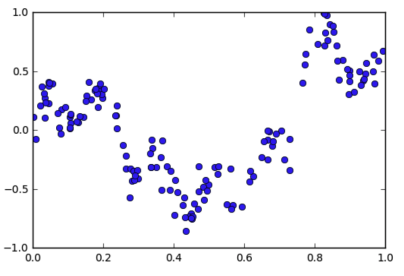

Let’s consider the problem of nonlinear regression. How can we model a function that fits complex, nonlinear data?

A common approach is to use basis function models, which transform the input into a new feature space where a linear model can be applied.

Linear Models with Basis Functions

We begin with a function of the form:

\[f(x) = \sum_{m=1}^{M} v_m h_m(x)\]Here, the \(h_m(x)\) are basis functions (also called feature functions), and \(v_m\) are their corresponding coefficients.

Example: In polynomial regression, the basis functions are \(h_m(x) = x^m\).

This method works well with standard linear model fitting techniques like least squares, lasso, or ridge regression. However, there’s a limitation: the basis functions \(h_1, \dots, h_M\) are fixed in advance.

What if we could learn these basis functions instead of fixing them?

Adaptive Basis Function Models

This idea leads us to adaptive basis function models, where we aim to learn both the coefficients and the basis functions:

\[f(x) = \sum_{m=1}^{M} v_m h_m(x), \quad \text{where } h_m \in \mathcal{H}\]Here, \(\mathcal{H}\) is a base hypothesis space of functions \(h : \mathcal{X} \to \mathbb{R}\). The combined hypothesis space is:

\[\mathcal{F}_M = \left\{ f(x) = \sum_{m=1}^{M} v_m h_m(x) \,\middle|\, v_m \in \mathbb{R},\, h_m \in \mathcal{H} \right\}\]The learnable parameters now include both the weights \(v_m\) and the functions \(h_m\) — this is what makes the model adaptive.

Here’s a simple analogy to help build intuition for adaptive basis function models:

Think of building a house: In a linear model with fixed basis functions, it’s like choosing from a catalog of pre-made furniture — your design is limited by what’s available. In contrast, adaptive basis functions let you custom-build each piece of furniture to fit your space and needs perfectly. You’re not just choosing the weights (how much furniture to use), you’re also designing what kind of furniture works best in each room.

In ML terms: Instead of relying on predefined transformations of input features (e.g., fixed polynomials), adaptive models learn which transformations (basis functions) are most useful for capturing the data’s patterns.

Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM)

To train adaptive basis function models, we rely on the principle of Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM).

The idea is simple: among all possible functions in our hypothesis space \(\mathcal{F}_M\), we want to find the one that minimizes the average loss over our training data. The loss function \(\ell(y, f(x))\) measures how far our prediction \(f(x)\) is from the true label \(y\) — common choices include squared loss, logistic loss, or exponential loss depending on the task.

Formally, our ERM objective is:

\[\hat{f} = \arg\min_{f \in \mathcal{F}_M} \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \ell(y_i, f(x_i))\]Now, expanding \(f(x)\) as a sum over learnable basis functions, we write:

\[f(x) = \sum_{m=1}^{M} v_m h_m(x)\]Plugging this into the ERM formulation, we get the following optimization objective:

\[J(v_1, \dots, v_M, h_1, \dots, h_M) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \ell \left( y_i, \sum_{m=1}^M v_m h_m(x_i) \right)\]This is the ERM objective we aim to minimize. The challenge now is: how do we optimize this objective when both the weights \(v_m\) and the basis functions \(h_m\) are learnable?

Gradient-Based Methods

Let’s first consider the case where our base hypothesis space \(\mathcal{H}\) is parameterized by a vector \(\theta \in \mathbb{R}^b\). That is, each basis function \(h_m\) is written as:

\[h(x; \theta_m) \in \mathcal{H}\]With this setup, our model becomes:

\[f(x) = \sum_{m=1}^M v_m h(x; \theta_m)\]Substituting into our ERM objective gives:

\[J(v_1, \dots, v_M, \theta_1, \dots, \theta_M) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \ell \left( y_i, \sum_{m=1}^M v_m h(x_i; \theta_m) \right)\]This formulation is powerful because we can now differentiate the loss \(\ell\) with respect to both:

- the weights \(v_m\) (which scale the outputs of each basis function), and

- the parameters \(\theta_m\) (which define the internal structure of each basis function).

If the loss function \(\ell\) is differentiable, and the basis functions \(h(x; \theta)\) are differentiable with respect to \(\theta\), then we can apply gradient-based optimization methods such as Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), Adam, or other first-order techniques to train the model end-to-end.

How Neural Networks Fit In

A classic example of this framework is a neural network:

- The network transforms the input \(x\) through multiple layers.

- The final output is a linear combination of the neurons in the last hidden layer — these neurons act as adaptive basis functions \(h_m(x; \theta_m)\).

- The weights \(v_m\) connect these neurons to the output layer.

Since both the neuron activations and the loss functions (like cross-entropy or MSE) are differentiable, we can compute gradients with respect to both \(v_m\) and \(\theta_m\). This is why training neural networks using backpropagation is possible — it’s essentially solving the ERM objective using gradient-based methods.

Wait, Aren’t Neural Networks Still Using Fixed Functions?

This is a question I found myself asking — and maybe you’re wondering the same:

“Aren’t neural networks still built from fixed components like linear combinations and activation functions? If so, are we really ‘learning’ basis functions — or just tuning weights inside a fixed structure?”

That’s a great observation — and you’re absolutely right in noting that each neuron has a predefined form: it performs a linear combination of its inputs followed by a non-linear activation, like \(\sigma(w^T x + b)\). The architecture — layers, activation functions, etc. — is fixed before training.

So what’s actually being learned?

While we don’t change the form of the individual components, neural networks adaptively construct complex functions by composing these fixed units across layers. Each layer transforms the representation from the previous one, and through this deep composition, the network can approximate highly non-linear functions.

Thus, neural networks fall under the broader umbrella of adaptive basis function models:

We don’t learn new basis function types from scratch, but we do learn how to combine and configure them to fit the data.

This makes neural networks extremely flexible — capable of learning complex patterns by tuning parameters inside a rich function space defined by their architecture.

With all that said, if you’re not familiar with this part about neural networks, no worries — feel free to skip it for now. We’ll dive deeper into it in a dedicated section later on.

For now, it’s important to understand that not all models support gradient-based optimization. So what happens when our basis functions are non-differentiable, like decision trees?

When Gradient-Based Methods Don’t Apply

So far, we’ve relied on the assumption that our basis functions are differentiable with respect to their parameters — allowing us to optimize the ERM objective using gradient-based methods. But what if this assumption doesn’t hold?

Let’s consider an important and widely-used case: when our base hypothesis space \(\mathcal{H}\) consists of decision trees.

Decision trees are non-parametric models. That is, they’re not defined by a small set of continuous parameters like \(\theta \in \mathbb{R}^b\). Instead, they involve discrete decisions — splitting data based on feature thresholds, forming branches and leaf nodes. This poses two fundamental challenges:

-

Non-differentiability: Even if we try to assign parameters to a decision tree (e.g., split thresholds, structure), the output of the tree does not change smoothly with respect to those parameters. Small changes in a split value can cause large, abrupt changes in the prediction.

-

Discontinuous prediction surfaces: Since decision trees partition the input space into disjoint regions, the function \(h(x)\) they represent is piecewise constant, which means it’s flat in regions and jumps discontinuously at split boundaries. Gradients simply don’t exist in such a surface.

Therefore, traditional gradient descent — which relies on computing derivatives — breaks down in this setting.

A Greedy, Stage-Wise Alternative

Despite the lack of gradients, we can still make progress using a greedy, stage-wise approach inspired by AdaBoost.

Recall how AdaBoost builds an ensemble by sequentially adding weak learners (like trees) to correct the errors of the previous ones. Even though it doesn’t explicitly minimize a loss function using gradients, it turns out that AdaBoost is implicitly minimizing exponential loss through a forward stage-wise additive modeling approach.

This insight opens the door to generalizing the idea:

Can we design a similar stage-wise additive method that explicitly minimizes a differentiable loss function, even when our base learners (like trees) are non-differentiable?

The answer is yes — and this leads us to the powerful technique of Gradient Boosting.

Gradient Boosting

Gradient Boosting combines the flexibility of additive models with the ability to optimize arbitrary differentiable loss functions — all while using non-differentiable base learners like decision trees.

But how is that possible?

The key idea is to perform gradient descent not in parameter space, but in function space.

In the next post, we’ll explore how Gradient Boosting interprets the optimization problem and fits a new base learner at each step by approximating the negative gradient of the loss with respect to the current model’s predictions.

This clever trick allows us to iteratively improve the model — even when the individual learners don’t support gradients themselves.

Stay tuned!