L1 and L2 Regularization - Nuanced Details

Regularization is a cornerstone in machine learning, providing a mechanism to prevent overfitting while controlling model complexity. Among the most popular techniques are L1 and L2 regularization, which serve different purposes but share a common goal of improving model generalization. In this post, we will delve deep into the theory, mathematics, and practical implications of these regularization methods.

Let’s set the stage with linear regression. For a dataset

\[D_n = \{(x_1, y_1), \dots, (x_n, y_n)\},\]the objective in ordinary least squares is to minimize the mean squared error:

\[\hat{w} = \arg\min_{w \in \mathbb{R}^d} \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \left( w^\top x_i - y_i \right)^2.\]While effective, this approach can overfit when the number of features \(d\) is large compared to the number of samples \(n\). For example, in natural language processing, it is common to have millions of features but only thousands of documents.

Addressing Overfitting with Regularization

To mitigate overfitting, \(L_2\) regularization (also known as ridge regression) adds a penalty term proportional to the \(L_2\) norm of the weights:

\[\hat{w} = \arg\min_{w \in \mathbb{R}^d} \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \left( w^\top x_i - y_i \right)^2 + \lambda \|w\|_2^2,\]where:

\[\|w\|_2^2 = w_1^2 + w_2^2 + \dots + w_d^2.\]This penalty term discourages large weight values, effectively shrinking them toward zero. When \(\lambda = 0\), the solution reduces to ordinary least squares. As \(\lambda\) increases, the penalty grows, favoring simpler models with smaller weights.

Understanding \(L_2\) Regularization

L2 regularization is particularly effective at reducing sensitivity to fluctuations in the input data. To understand this, consider a simple linear function:

\[\hat{f}(x) = \hat{w}^\top x.\]The function \(\hat{f}(x)\) is said to be Lipschitz continuous, with a Lipschitz constant defined as:

\[L = \|\hat{w}\|_2.\]This implies that when the input changes from \(x\) to \(x + h\), the function’s output change is bounded by \(L\|h\|_2\). In simpler terms, \(L_2\) regularization controls the rate of change of \(\hat{f}(x)\), making the model less sensitive to variations in the input data.

Mathematical Proof of Lipschitz Continuity

To formalize this property, let’s derive the Lipschitz bound:

\[|\hat{f}(x + h) - \hat{f}(x)| = |\hat{w}^\top (x + h) - \hat{w}^\top x| = |\hat{w}^\top h|.\]Using the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, this can be bounded as:

\[|\hat{w}^\top h| \leq \|\hat{w}\|_2 \|h\|_2.\]Thus, the Lipschitz constant \(L = \|\hat{w}\|_2\) quantifies the maximum rate of change for the function \(\hat{f}(x)\).

Generalization to Other Norms

The generalization to other norms comes from the equivalence of norms in finite-dimensional vector spaces. Here’s the reasoning:

Norm Equivalence:

In finite-dimensional spaces (e.g., \(\mathbb{R}^d\)), all norms are equivalent. This means there exist constants \(C_1, C_2 > 0\) such that for any vector \(\mathbf{w} \in \mathbb{R}^d\):

\[C_1 \| \mathbf{w} \|_p \leq \| \mathbf{w} \|_q \leq C_2 \| \mathbf{w} \|_p\]For example, the \(L_1\), \(L_2\), and \(L_\infty\) norms can all bound one another with appropriate scaling constants.

Lipschitz Continuity:

The Lipschitz constant for \(\hat{f}(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x}\) depends on the norm of \(\mathbf{w}\) because the bound for the rate of change involves the norm of \(\mathbf{w}\). When using a different norm \(\| \cdot \|_p\) to regularize, the Lipschitz constant adapts to that norm.

Specifically, for the \(L_p\) norm:

\[| \hat{f}(\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{h}) - \hat{f}(\mathbf{x}) | \leq \| \mathbf{w} \|_p \| \mathbf{h} \|_q\]where \(p\) and \(q\) satisfies:

\[\frac{1}{p} + \frac{1}{q} = 1\]Key Insight:

This shows that the idea of controlling the sensitivity of the model (through the Lipschitz constant) extends naturally to any norm. The choice of norm alters how the regularization penalizes weights but retains the fundamental property of bounding the function’s rate of change.

An analogy to internalize this:

Think of \(L_2\) regularization as a bungee cord attached to a daring rock climber. The climber represents the model trying to navigate a complex landscape (data). Without the cord (regularization), they might venture too far and fall into overfitting. The cord adds just enough tension (penalty) to keep the climber balanced and safe, ensuring they explore the terrain without taking reckless leaps. Similarly, regularization helps the model stay grounded, generalizing well without succumbing to overfitting.

Now, imagine different types of bungee cords for different norms. The \(L_2\) regularization bungee cord is like a standard elastic cord, providing a smooth and consistent tension, ensuring the climber doesn’t over-extend but can still make significant progress.

For \(L_1\) regularization, the bungee cord is more rigid and less forgiving, preventing large movements in any direction. It forces the climber to stick to fewer, more significant paths, like sparsity in feature selection — only the most important features remain.

In the case of \(L_\infty\) regularization, the bungee cord has a fixed maximum stretch. No matter how hard the climber tries to move, they cannot go beyond a certain point, ensuring the model remains under tight control, limiting the complexity of each individual parameter.

In each case, the regularization (the cord) helps the climber (the model) stay within safe bounds, preventing them from falling into overfitting while ensuring they can still navigate the data effectively.

Linear vs. Ridge Regression

The inclusion of L2 regularization modifies the optimization objective, as illustrated by the difference between linear regression and ridge regression.

In linear regression, the goal is to minimize the sum of squared residuals, expressed as:

\[L(w) = \frac{1}{2} \|Xw - y\|_2^2\]In contrast, ridge regression introduces an additional penalty term proportional to the L2 norm of the weights:

\[L(w) = \frac{1}{2} \|Xw - y\|_2^2 + \frac{\lambda}{2} \|w\|_2^2\]This additional term penalizes large weights, helping to control model complexity and reduce overfitting.

Gradients of the Objective:

The inclusion of the regularization term affects the gradient of the loss function. For linear regression, the gradient is:

\[\nabla L(w) = X^T (Xw - y)\]For ridge regression, the gradient becomes:

\[\nabla L(w) = X^T (Xw - y) + \lambda w\]The regularization term \(\lambda w\) biases the solution toward smaller weights, thereby stabilizing the optimization. By adding this term, the model is less sensitive to small changes in the data, especially in cases where multicollinearity exists, i.e., when features are highly correlated.

Closed-form Solutions:

Both linear regression and ridge regression admit closed-form solutions. For linear regression, the weights are given by:

\[w = (X^T X)^{-1} X^T y\]For ridge regression, the solution is slightly modified:

\[w = (X^T X + \lambda I)^{-1} X^T y\]The addition of \(\lambda I\) ensures that \(X^T X + \lambda I\) is always invertible, addressing potential issues of singularity in the design matrix. In linear regression, if the matrix \(X^T X\) is singular or nearly singular (which can occur when features are linearly dependent or when there are more features than samples), the inverse may not exist or be unstable. By adding \(\lambda I\), where \(I\) is the identity matrix, we effectively shift the eigenvalues of \(X^T X\), making the matrix non-singular and ensuring a stable solution.

A Constrained Optimization Perspective

L2 regularization can also be understood through the lens of constrained optimization. In this perspective, the ridge regression objective is expressed in Tikhonov regularization form as:

\[w^* = \arg\min_w \left( \frac{1}{2} \|Xw - y\|_2^2 + \frac{\lambda}{2} \|w\|_2^2 \right)\]The Ivanov form is another perspective where the objective is similarly constrained, but the constraint is typically applied in a more specific way, usually in the context of ill-posed problems or regularization approaches in functional analysis. It focuses on minimizing the error while controlling the solution’s smoothness or complexity. While this form is less commonly used directly in machine learning, it is foundational in understanding regularization in more theoretical settings. We mention this now because both forms will appear later in the discussion of other concepts, and it’s helpful to have a brief overview before we revisit them in more depth.

Alternatively, using Lagrangian theory, we can reframe ridge regression as a constrained optimization problem. The objective is to minimize the residual sum of squares subject to a constraint on the L2 norm of the weights:

\[w^* = \arg\min_{w : \|w\|_2^2 \leq r} \frac{1}{2} \|Xw - y\|_2^2\]Here, \(r\) represents the maximum allowed value for the squared norm of the weights, effectively placing a limit on their size. The Lagrange multiplier adjusts the importance of the constraint during optimization. This form emphasizes the constraint on model complexity, ensuring that the weights don’t grow too large.

At the optimal solution, the gradients of the objective function and the constraint term balance each other, providing a geometric interpretation of how regularization controls the model complexity.

Note: The Lagrangian theory will be explored further when we discuss Support Vector Machines (SVMs), where this approach plays a central role in optimization.

Lasso Regression and \(L_1\) Regularization

While L2 regularization minimizes the sum of squared weights, L1 regularization (used in Lasso regression) minimizes the sum of absolute weights. This is expressed as:

\[w^* = \arg\min_{w \in \mathbb{R}^d} \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n (\hat{w}^T x_i - y_i)^2 + \lambda \|w\|_1\]Here, the L1 norm

\[\|w\|_1 = |w_1| + |w_2| + \dots + |w_d|\]encourages sparsity in the weight vector, setting some coefficients exactly to zero. But what’s behind this, really? Keep reading!

Ridge vs. Lasso Regression

The key difference between ridge and lasso regression lies in their impact on the weights. Ridge regression tends to shrink all coefficients toward zero but does not eliminate any of them. In contrast, lasso regression produces sparse solutions, where some coefficients are exactly zero. We’ll dive into this next.

This sparsity has significant practical advantages. By zeroing out irrelevant features, lasso regression simplifies the model, making it:

- Faster to compute, as fewer features need to be processed.

- Cheaper to store and deploy, especially on resource-constrained devices.

- More interpretable, as it highlights the most important features.

- Less prone to overfitting, since the reduced complexity often leads to better generalization.

Why Does \(L_1\) Regularization Lead to Sparsity?

A distinctive property of L1 regularization is its ability to produce sparse solutions, where some weights are exactly zero. This characteristic makes L1 regularization particularly useful for feature selection, as it effectively identifies the most important features by eliminating irrelevant ones. To understand this better, let’s explore the theoretical underpinnings and geometric intuition behind this phenomenon.

Revisiting Lasso Regression:

Lasso regression penalizes the L1 norm of the weights. The objective function, also known as the Tikhonov form, is given by:

\[\hat{w} = \arg\min_{w \in \mathbb{R}^d} \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \big(w^T x_i - y_i\big)^2 + \lambda \|w\|_1\]Here, the L1 norm is defined as:

\[\|w\|_1 = |w_1| + |w_2| + \dots + |w_d|\]This formulation encourages sparsity by applying a uniform penalty across all weights, effectively “pushing” some weights to zero when they contribute minimally to the prediction.

Regularization as Constrained Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM)

Regularization can also be viewed through the lens of constrained ERM. For a given complexity measure \(\Omega\) and a fixed threshold \(r \geq 0\), the optimization problem is expressed as:

\[\min_{f \in \mathcal{F}} \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \ell(f(x_i), y_i) \quad \text{s.t.} \quad \Omega(f) \leq r\]In the case of Lasso regression, this is equivalent to the Ivanov form:

\[\hat{w} = \arg\min_{\|w\|_1 \leq r} \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \big(w^T x_i - y_i\big)^2\]Here, \(r\) plays the same role as the regularization parameter \(\lambda\) in the penalized ERM (Tikhonov) form. The choice between these forms depends on whether the complexity is penalized directly or constrained explicitly.

The ℓ1 and ℓ2 Norm Constraints

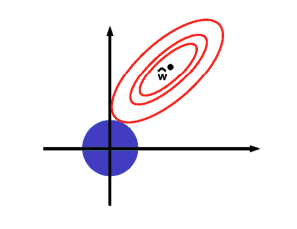

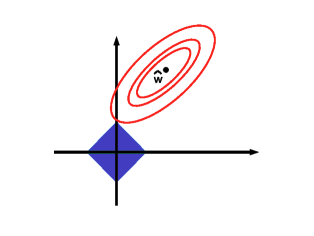

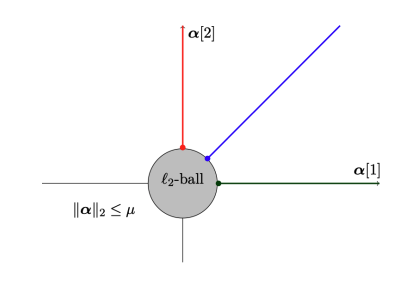

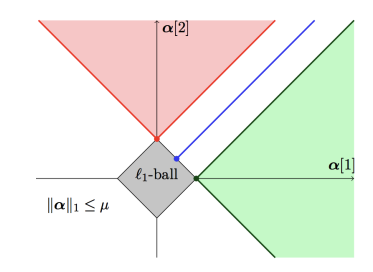

To understand why L1 regularization promotes sparsity, consider a simple hypothesis space \(\mathcal{F} = \{f(x) = w_1x_1 + w_2x_2\}\). Each function can be represented as a point \((w_1, w_2)\) in \(\mathbb{R}^2\). The regularization constraints can be visualized as follows:

- L2 norm constraint: \(w_1^2 + w_2^2 \leq r\), which is a circle in \(\mathbb{R}^2\).

- L1 norm constraint: \(|w_1| + |w_2| \leq r\), which forms a diamond in \(\mathbb{R}^2\).

Note: The sparse solutions correspond to the vertices of the diamond, where at least one weight is zero.

To build intuition, let’s analyze the geometry of the optimization:

- The blue region represents the feasible space defined by the regularization constraint (e.g., \(w_1^2 + w_2^2 \leq r\) for L2, or \(|w_1| + |w_2| \leq r\) for L1).

-

The red contours represent the level sets of the empirical risk function:

\[\hat{R}_n(w) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \big(w^T x_i - y_i\big)^2\]

The optimal solution is found where the smallest contour intersects the feasible region. For L1 regularization, this intersection tends to occur at the corners of the diamond, where one or more weights are exactly zero.

Suppose the loss contours grow as perfect circles (or spheres in higher dimensions). When these contours intersect the diamond-shaped feasible region of L1 regularization, the corners of the diamond are more likely to be touched. These corners correspond to solutions where at least one weight is zero.

In contrast, for L2 regularization, the feasible region is a circle (or sphere), and the intersection is equally likely to occur in any direction. This results in small, but non-zero, weights across all features, rather than sparse solutions.

Optimization Perspective:

From an optimization viewpoint, the difference between L1 and L2 regularization lies in how the penalty affects the gradient:

- For L2 regularization, as a weight \(w_i\) becomes smaller, the penalty \(\lambda w_i^2\) decreases more rapidly. However, the gradient of the penalty also diminishes, providing less incentive to shrink the weight to exactly zero.

- For L1 regularization, the penalty \(\lambda |w_i|\) decreases linearly, and its gradient remains constant regardless of the weight’s size. This consistent gradient drives small weights to zero, promoting sparsity.

Consider the following idea: Imagine you’re packing items into a small rectangular box, and you have two kinds of items: rigid boxes (representing \(L_1\) regularization) and pebbles (representing \(L_2\) regularization).

The rigid boxes are shaped with sharp corners and don’t squish or deform. When you try to fit them into the small box, they naturally stack at the edges or corners of the space. This means some of the rigid boxes might not fit at all, so you leave them out—just like \(L_1\) regularization pushing weights to zero.

The pebbles, on the other hand, are smooth and can be squished slightly. When you pack them into the box, they distribute evenly, filling in gaps without leaving any pebbles completely outside. This is like \(L_2\) regularization, where weights are reduced but not exactly zero.

So, that’s why \(L_1\) regularization creates sparse solutions (only the most critical items get packed) while \(L_2\) regularization spreads the influence across all features (everything gets included, but smaller).

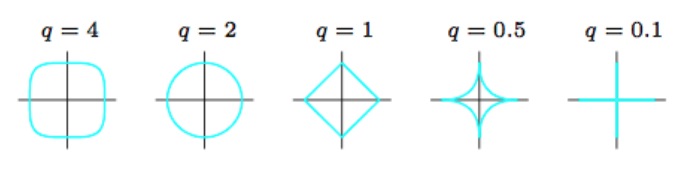

Generalizing to \(\ell_q\) Regularization

\(\ell_1\) and \(\ell_2\) regularization are specific cases of the more general \(\ell_q\) regularization, defined as:

\[\|w\|_q^q = |w_1|^q + |w_2|^q + \dots + |w_d|^q\]

Here are some notable cases:

- For \(q \geq 1\), \(\|w\|_q\) is a valid norm.

- For \(0 < q < 1\), the constraint becomes non-convex, making optimization challenging. While \(\ell_q\) regularization with \(q < 1\) can induce even sparser solutions than L1, it is often impractical in real-world scenarios. For instance when \(q=0.5\), the regularization takes the form of a square root function, which is non-convex.

- The \(\ell_0\) norm, defined as the number of non-zero weights, corresponds to subset selection but is computationally infeasible due to its combinatorial nature.

Note: \(L_n\)and \(\ell_n\) represent the same concept, so don’t let the difference in notation confuse you.

Conclusion

\(L_1\) regularization’s sparsity-inducing property makes it an indispensable tool in feature selection and high-dimensional problems. Its optimization characteristics and ability to simplify models while retaining interpretability set it apart from \(L_2\) regularization.

Next, we’ll talk about the maximum margin classifier & SVM. Stay tuned, as moving on, it’s going to get a little intense, but don’t worry—we’ll get through it together!

References

- why-l1-norm-for-sparse-models

- L1 Norm Regularization and Sparsity Explained for Dummies

- why-small-l1-norm-means-sparsity

- Regularization path using Lasso regression

- Image Credits: Mairal et al.’s Sparse Modeling for Image and Vision Processing Fig 1.6, KPM Fig. 13