Loss Functions - Regression and Classification

Loss functions are of critical importance to machine learning, guiding models to minimize errors and improve predictions. They quantify how far off a model’s predictions are from the actual outcomes and serve as the basis for optimization. In this post, we’ll explore loss functions for regression and classification problems, breaking down their mathematical foundations and building intuitive understanding along the way. We will then transition our focus to logistic regression, examining its relationship with loss functions in classification tasks.

Loss Functions for Regression

Regression tasks focus on predicting continuous values. Think about forecasting stock prices, estimating medical costs based on patient details, or predicting someone’s age from their photograph. These problems share a common requirement: accurately measuring how close the predicted values are to the true values.

Setting the Stage: Notation

Before diving in, let’s clarify the notation:

- \(\hat{y}\) represents the predicted value (the model’s output).

- \(y\) denotes the actual observed value (the ground truth).

A loss function for regression maps the predicted and actual values to a real number: \(\ell(\hat{y}, y) \in \mathbb{R}.\) Most regression losses are based on the residual, defined as:

\[r = y - \hat{y}\]The residual captures the difference between the true value and the prediction.

What Makes a Loss Function Distance-Based?

A loss function is distance-based if it meets two criteria:

- It depends solely on the residual: \(\ell(\hat{y}, y) = \psi(y - \hat{y}),\) where \(\psi: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}.\)

- It equals zero when the residual is zero: \(\psi(0) = 0.\)

Such loss functions are translation-invariant, meaning they remain unaffected if both the prediction and the actual value are shifted by the same amount: \(\ell(\hat{y} + b, y + b) = \ell(\hat{y}, y), \quad \forall b \in \mathbb{R}.\)

However, in some scenarios, translation invariance may not be desirable. For example, using the relative error: \(\text{Relative error} = \frac{\hat{y} - y}{y},\) provides a loss function better suited to cases where proportional differences matter.

For instance:

- If the actual stock price is $100, and your model predicts $110, the absolute error is $10, but the relative error is 10%.

- But, if the actual stock price is $10, and your model predicts $11, the absolute error is still $1, but the relative error is 10%.

Exploring Common Loss Functions for Regression

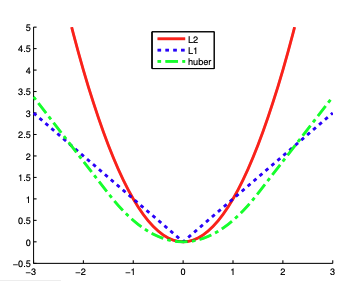

1. Squared Loss (L2 Loss)

Squared loss is one of the most widely used loss functions:

\[\ell(r) = r^2 = (y - \hat{y})^2\]This loss penalizes large residuals more heavily, making it sensitive to outliers. Its simplicity and differentiability make it popular in linear regression and similar models.

2. Absolute Loss (L1 Loss)

Absolute loss measures the magnitude of the residual:

\[\ell(r) = |r| = |y - \hat{y}|\]Unlike squared loss, absolute loss is robust to outliers but lacks smooth differentiability.

Think of it this way: Imagine predicting house prices based on size. If one house in the dataset has an extremely high price (an outlier), using absolute loss will make the model focus more on the typical pricing pattern of most houses and ignore the outlier. In contrast, least squares regression would try to minimize the error caused by that outlier, potentially distorting the model.

3. Huber Loss

The Huber loss combines the best of both worlds:

\[\ell(r) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{2}r^2 & \text{if } |r| \leq \delta, \\ \delta |r| - \frac{1}{2}\delta^2 & \text{if } |r| > \delta. \end{cases}\]For small residuals, it behaves like squared loss, while for large residuals, it switches to absolute loss, providing robustness without sacrificing differentiability. Note: Equal values and slopes at \((r = \delta)\).

Understanding Robustness: It describes a loss function’s resistance to the influence of outliers.

- Squared loss is highly sensitive to outliers.

- Absolute loss is much more robust.

- Huber loss strikes a balance between sensitivity and robustness. Meaning, it is sensitive enough to provide a useful gradient for smaller errors (via L2), but becomes more robust to large residuals, preventing them from disproportionately influencing the model (via L1).

Loss Functions for Classification

Classification tasks involve predicting discrete labels. For instance, we might want to decide whether an email is spam or if an image contains a cat. The challenge lies in guiding the model to make accurate predictions while quantifying the degree of correctness.

The Role of the Score Function

In binary classification, the model predicts a score, \(f(x)\), for each input \(x\):

- If \(f(x) > 0\), the model predicts the label \(1\).

- If \(f(x) < 0\), the model predicts the label \(-1\).

This score represents the model’s confidence, and its magnitude indicates how certain the prediction is.

What is the Margin?

The margin captures the relationship between the predicted score and the true label:

\[m = y\hat{y}\]or equivalently:

\[m = yf(x)\]The margin measures correctness:

- Positive margin: The prediction is correct.

- Negative margin: The prediction is incorrect.

The goal of many classification tasks is to maximize this margin, ensuring confident and accurate predictions.

Common Loss Functions for Classification

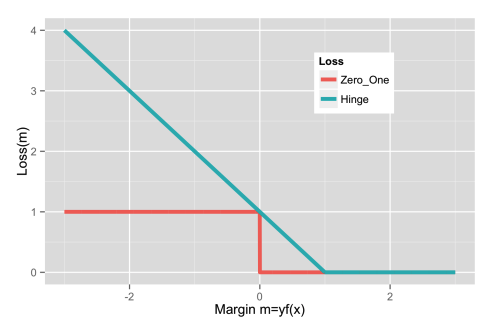

1. 0-1 Loss

The 0-1 loss is a simple yet impractical loss function:

\[\ell(y, \hat{y}) = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } y = \hat{y} \\ 1 & \text{if } y \neq \hat{y} \end{cases}\]Alternatively,

\[\ell_{0-1}(f(x), y) = \mathbf{1}[yf(x) \leq 0]\]Here, \(\mathbf{1}\) is the indicator function, which equals 1 if the condition is true and 0 otherwise.

Although intuitive, the 0-1 loss is:

- Non-convex, making optimization difficult, because its value is either 0 or 1, which creates a step-like behavior.

- Non-differentiable, rendering gradient-based methods inapplicable. For instance, if \(\hat{y} = 0.5\), the loss could change abruptly from 0 to 1 depending on whether the true label \(y\) is 0 or 1, leading to no gradient at this boundary.

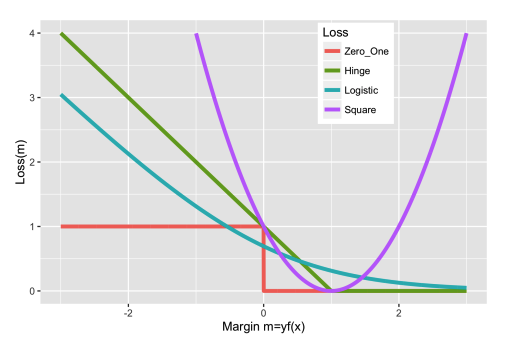

2. Hinge Loss

Hinge loss, commonly used in Support Vector Machines (SVMs), addresses the limitations of 0-1 loss:

\[\ell_{\text{Hinge}}(m) = \max(1 - m, 0)\]It is a convex, upper bound on 0-1 loss and encourages a positive margin. However, it is not differentiable at \(m = 1\).

Diving Deeper: Logistic Regression

In our exploration above, we’ve covered the basics of regression and classification losses. Now, let’s shift our focus to logistic regression and its corresponding loss functions, which are pivotal in classification problems. We’ll also touch on why square loss isn’t typically used for classification.

Despite its name, logistic regression is not actually a regression algorithm—it’s a linear classification method. Logistic regression predicts probabilities, making it well-suited for binary classification problems.

The predictions are modeled using the sigmoid function, denoted by \(\sigma(z)\), where:

\[\sigma(z) = \frac{1}{1 + \exp(-z)}\]and \(z = f(x) = w^\top x\) is the score computed from the input features and weights.

Logistic Regression with Labels as 0 or 1

When the labels are in \(\{0, 1\}\):

-

The predicted probability is: \(\hat{y} = \sigma(z)\)

-

The loss function for logistic regression in this case is the binary cross-entropy loss:

\[\ell_{\text{Logistic}} = -y \log(\hat{y}) - (1 - y) \log(1 - \hat{y})\]

Here’s how it works based on different predicted values of \(\hat{y}\):

- If \(y = 1\) (True label is 1):

-

The loss is:

\[\ell_{\text{Logistic}} = -\log(\hat{y})\]This means if the predicted probability \(\hat{y}\) is close to 1 (i.e., the model is confident that the class is 1), the loss will be very small (approaching 0). On the other hand, if \(\hat{y}\) is close to 0, the loss becomes large, penalizing the model for being very wrong.

-

- If \(y = 0\) (True label is 0):

-

The loss is:

\[\ell_{\text{Logistic}} = -\log(1 - \hat{y})\]In this case, if the predicted probability \(\hat{y}\) is close to 0 (i.e., the model correctly predicts the class as 0), the loss will be very small (approaching 0). However, if \(\hat{y}\) is close to 1, the loss becomes large, penalizing the model for incorrectly predicting class 1.

-

Example of Different Predicted Values:

- For a true label \(y = 1\):

-

If \(\hat{y} = 0.9\): \(\ell_{\text{Logistic}} = -\log(0.9) \approx 0.105\) This is a small loss, since the model predicted a high probability for class 1, which is correct.

-

If \(\hat{y} = 0.1\): \(\ell_{\text{Logistic}} = -\log(0.1) \approx 2.302\) This is a large loss, since the model predicted a low probability for class 1, which is incorrect.

-

- For a true label \(y = 0\):

-

If \(\hat{y} = 0.1\): \(\ell_{\text{Logistic}} = -\log(1 - 0.1) \approx 0.105\) This is a small loss, since the model predicted a low probability for class 1, which is correct.

-

If \(\hat{y} = 0.9\): \(\ell_{\text{Logistic}} = -\log(1 - 0.9) \approx 2.302\) This is a large loss, since the model predicted a high probability for class 1, which is incorrect.

-

Key Points:

- The negative sign in the loss function ensures that when the model predicts correctly (i.e., \(\hat{y}\) is close to the true label), the loss is minimized (approaching 0).

- The loss grows as the predicted probability \(\hat{y}\) moves away from the true label \(y\), and it grows more rapidly as the predicted probability becomes more confident but incorrect.

Logistic Regression with Labels as -1 or 1

When the labels are in \(\{-1, 1\}\), the sigmoid function simplifies using the property: \(1 - \sigma(z) = \sigma(-z).\)

This allows us to express the loss equivalently as:

\[\ell_{\text{Logistic}} = \begin{cases} -\log(\sigma(z)) & \text{if } y = 1, \\ -\log(\sigma(-z)) & \text{if } y = -1. \end{cases}\]Simplifying further:

\[\ell_{\text{Logistic}} = -\log(\sigma(yz)) = -\log\left(\frac{1}{1 + e^{-yz}}\right) = \log(1 + e^{-m})\]where \(m = yz\) is the margin.

Key Insights of Logistic loss:

- Is differentiable, enabling gradient-based optimization.

- Always rewards larger margins, encouraging more confident predictions.

- Never becomes zero, ensuring continuous optimization pressure.

What About Square Loss for Classification?

Square loss, while effective for regression, is rarely used for classification. Let’s break it down:

\[\ell(f(x), y) = (f(x) - y)^2\]For binary classification where \(y \in \{-1, 1\}\), we can rewrite this in terms of the margin:

\[\ell(f(x), y) = (f(x) - y)^2 = f^2(x) - 2f(x)y + y^2.\]Using the fact that \(y^2 = 1\):

\[\ell(f(x), y) = f^2(x) - 2f(x)y + 1 = (1 - f(x)y)^2 = (1 - m)^2.\]Why Not Use Square Loss?

Square loss heavily penalizes outliers, such as mislabeled examples, making it unsuitable for classification tasks where robust performance on noisy data is crucial.

Conclusion

Loss functions form the backbone of machine learning, providing a mathematical framework for optimization. A quick recap:

- Regression Losses:

- Squared (L2) loss: Sensitive to outliers.

- Absolute (L1) loss: Robust but non-differentiable.

- Huber loss: Balances robustness and smoothness.

- Classification Losses:

- Hinge loss: Encourages a large positive margin (used in SVMs).

- Logistic loss: Differentiable and rewards confidence.

These concepts tie back to critical components of machine learning workflows, such as gradient descent, which relies on the properties of loss functions to update model parameters effectively.

Up next, we’ll dive into Regularization, focusing on how it combats overfitting and improves model performance. Stay tuned!