Understanding the Maximum Margin Classifier

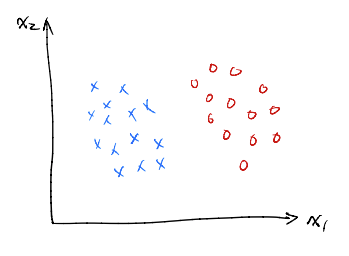

Linearly Separable Data

Let’s start with the simplest case: linearly separable data. Imagine a dataset where we can draw a straight line (or more generally, a hyperplane in higher dimensions) to perfectly separate two classes of points. Formally, for a dataset \(D\) with points \((x_i, y_i)\), we seek a hyperplane that satisfies the following conditions:

- \(w^T x_i > 0\) for all \(x_i\) where \(y_i = +1\),

- \(w^T x_i < 0\) for all \(x_i\) where \(y_i = -1\).

This hyperplane is defined by a weight vector \(w\) and a bias \(b\), and our goal is to find \(w\) and \(b\) such that all points are correctly classified.

But how do we design a learning algorithm to find such a hyperplane? This brings us to the Perceptron Algorithm.

The Perceptron Algorithm

The perceptron is one of the earliest learning algorithms developed to find a separating hyperplane. Here’s how it works: we start with an initial guess for \(w\) (usually a zero vector) and iteratively adjust it based on misclassified examples.

Each time we encounter a point \((x_i, y_i)\) that is misclassified (i.e., \(y_i w^T x_i < 0\)), we update the weight vector as follows:

\[w \gets w + y_i x_i.\]This update rule ensures that the algorithm moves the hyperplane towards misclassified positive examples and away from misclassified negative examples.

The perceptron algorithm has a remarkable property: if the data is linearly separable, it will converge to a solution with zero classification error in a finite number of steps.

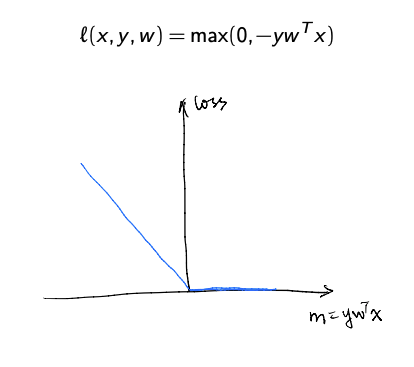

In terms of loss functions, the perceptron can be viewed as minimizing the hinge loss:

However, while the perceptron guarantees a solution, it doesn’t always find the best one. This brings us to the concept of maximum-margin classifiers. But before exploring that, let’s take a deeper look at why the this update rule works.

Understanding why the Perceptron Update Rule works?

The perceptron update rule shifts the hyperplane differently depending on whether the misclassified point belongs to the positive class (\(y_i = 1\)) or the negative class (\(y_i = -1\)). Let’s take the two cases:

Positive Case (\(y_i = 1\))

-

Condition for misclassification: \(w^T x_i < 0.\)

This means the point \(x_i\) is on the wrong side of the hyperplane or too far from the correct side. -

Update rule:

\[w \gets w + x_i.\] -

Effect of the update:

- Adding \(x_i\) to \(w\) increases the dot product \(w^T x_i\) because \(w\) is now pointing more in the direction of \(x_i\).

- This adjustment shifts the hyperplane towards \(x_i\), ensuring \(x_i\) is more likely to be correctly classified in the next iteration.

Negative Case (\(y_i = -1\))

-

Condition for misclassification: \(w^T x_i > 0.\)

This means the point \(x_i\) is either incorrectly classified as positive or too close to the positive side. -

Update rule:

\[w \gets w - x_i.\] -

Effect of the update:

- Subtracting \(x_i\) from \(w\) decreases the dot product \(w^T x_i\) because \(w\) is now pointing less in the direction of \(x_i\).

- This adjustment shifts the hyperplane away from \(x_i\), making it more likely to correctly classify \(x_i\) as negative in subsequent iterations.

Geometric Interpretation: The perceptron update ensures that the weight vector \(w\) aligns more closely with the correctly classified side.

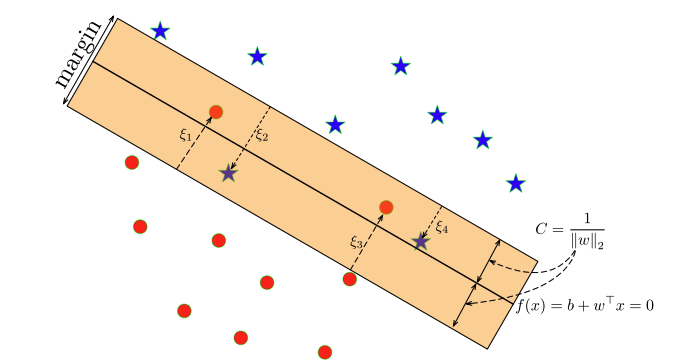

Maximum-Margin Separating Hyperplane

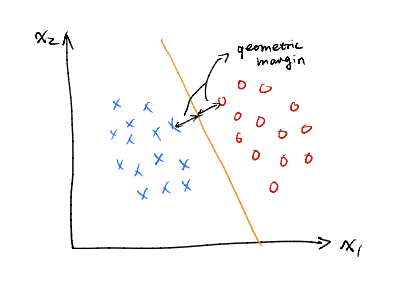

When the data is linearly separable, there are infinitely many hyperplanes that can separate the classes. The perceptron algorithm, for instance, might return any one of these. But not all hyperplanes are equally desirable.

We prefer a hyperplane that is farthest from both classes of points. This idea leads to the concept of the maximum-margin classifier, which finds the hyperplane that maximizes the smallest distance between the hyperplane and the data points.

Geometric Margin

The geometric margin of a hyperplane is defined as the smallest distance between the hyperplane and any data point. For a hyperplane defined by \(w\) and \(b\), this margin can be expressed as:

\[\gamma = \min_i \frac{y_i (w^T x_i + b)}{\|w\|_2}.\]

Maximizing this geometric margin provides a hyperplane that is robust to small perturbations in the data, making it a desirable choice.

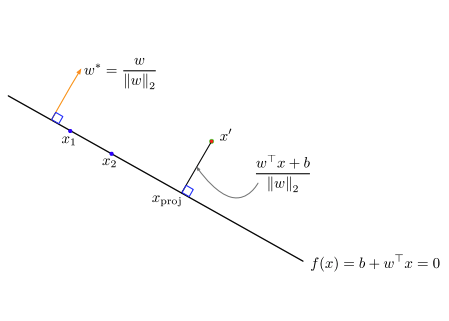

Distance Between a Point and a Hyperplane

To understand the geometric margin more concretely, let’s calculate the distance from a point \(x'\) to a hyperplane \(H: w^T v + b = 0\). This derivation involves the following steps:

Step 1: Perpendicular Distance from a Point to a Hyperplane

The distance from a point \(x'\) to the hyperplane is defined as the shortest (perpendicular) distance between the point and the hyperplane. The equation of the hyperplane is:

\[w^T v + b = 0,\]where:

- \(w\) is the normal vector to the hyperplane.

- \(b\) is the bias term.

- \(v\) represents any point on the hyperplane.

Step 2: Projecting the Point onto the Normal Vector

The perpendicular distance is proportional to the projection of the point \(x'\) onto the normal vector \(w\). Mathematically, the projection of \(x'\) onto \(w\), denoted \(\text{Proj}_{w}(x')\), is given by:

\[\text{Proj}_{w}(x') = \frac{x' \cdot w}{w \cdot w} w = \left( \frac{w^T x'}{\|w\|_2^2} \right) w\]For the hyperplane \(H: w^T v + b = 0\), the bias term \(b\) shifts the hyperplane as the hyperplane is not always centered at the origin Incorporating this into the projection formula, the signed distance becomes:

\[d(x', H) = \frac{w^T x' + b}{\|w\|_2}.\]Step 3: Accounting for the Label \(y\)

The label \(y\) of the point \(x'\) determines whether the point is on the positive or negative side of the hyperplane:

- For correctly classified points, \(y (w^T x' + b) > 0\).

- For misclassified points, \(y (w^T x' + b) < 0\).

Including the label ensures that the signed distance is positive for correctly classified points and negative for misclassified points. Thus, the signed distance becomes:

\[d(x', H) = \frac{y (w^T x' + b)}{\|w\|_2}.\]Maximizing the Margin

To maximize the margin, we solve the following optimization problem:

\[\max \min_i \frac{y_i (w^T x_i + b)}{\|w\|_2}.\]To simplify, let \(M = \min_i \frac{y_i (w^T x_i + b)}{\|w\|_2}\). The problem becomes:

\[\max M, \quad \text{subject to } \frac{y_i (w^T x_i + b)}{\|w\|_2} \geq M, \; \forall i.\]This means: We want to maximize \(M\), which corresponds to maximizing the smallest margin across all data points.

The constraint: \(\frac{y_i (w^T x_i + b)}{\|w\|_2} \geq M\) ensures that for every data point \(x_i\), the margin is at least \(M\), i.e., the data point lies on the correct side of the margin boundary.

Another way to put this is: Since \(M\) is the smallest margin, the constraint \(\frac{y_i (w^T x_i + b)}{\|w\|_2} \geq M\) ensures that every data point has a margin at least as large as \(M\) and this condition is enforced for every data point \(i\).

Next, by fixing \(\|w\|_2 = \frac{1}{M}\), we reformulate it as:

\[\min \frac{1}{2} \|w\|_2^2, \quad \text{subject to } y_i (w^T x_i + b) \geq 1, \; \forall i.\]This is the optimization problem solved by a hard margin support vector machine (SVM).

Note: Maximizing the margin \(M\) is equivalent to minimizing the inverse, \(\frac{1}{2} \|w\|_2^2\), since the margin is inversely proportional to the norm of \(w\).

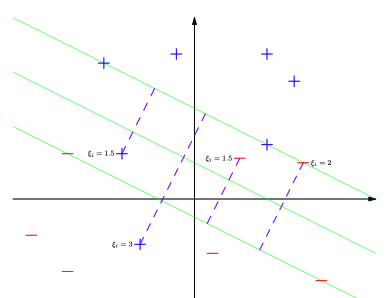

What If the Data Is Not Linearly Separable?

In real-world scenarios, data is often not perfectly linearly separable. For any \(w\), there might be points with negative margins. To handle such cases, we introduce slack variables \(\xi_i\), which allow some margin violations.

Soft Margin SVM

The optimization problem for a soft margin SVM is:

\[\min \frac{1}{2} \|w\|_2^2 + C \sum_{i=1}^n \xi_i,\]subject to:

\[y_i (w^T x_i + b) \geq 1 - \xi_i, \quad \xi_i \geq 0, \; \forall i.\]Breaking this down:

-

Regularization Term:

\[\frac{1}{2} \|w\|_2^2\]This term is the regularization component of the objective function. It penalizes large values of \(w\), which corresponds to smaller margins. By minimizing this term, we aim to maximize the margin between the two classes. A larger margin typically leads to better generalization and lower overfitting.

-

Penalty Term:

\[C \sum_{i=1}^n \xi_i\]This term introduces penalties for margin violations. The \(\xi_i\) are the slack variables that measure how much each data point violates the margin. The parameter \(C\) controls the trade-off between maximizing the margin (by minimizing \(\|w\|_2^2\)) and minimizing the violations (the sum of the slack variables).

- A larger value of \(C\) places more emphasis on minimizing violations, which results in a stricter margin but could lead to overfitting if \(C\) is too large.

- A smaller value of \(C\) allows for more margin violations, potentially leading to a wider margin and better generalization.

-

Margin Constraint:

\[y_i (w^T x_i + b) \geq 1 - \xi_i\]This constraint ensures that the data points are correctly classified with a margin of at least 1, unless there is a violation. If a data point violates the margin (i.e., it lies inside the margin or on the wrong side of the hyperplane), the slack variable \(\xi_i\) becomes positive. The value of \(\xi_i\) measures how much the margin is violated for the data point \(x_i\).

-

When \(\xi_i = 0\), the data point \(x_i\) satisfies the margin condition:

\[y_i (w^T x_i + b) \geq 1\]This represents the ideal case where the point lies correctly outside or on the margin.

-

When \(\xi_i > 0\), the point violates the margin. The larger the value of \(\xi_i\), the greater the violation. For example, if \(\xi_i = 0.5\), the point lies inside the margin or is misclassified by 0.5 units.

-

-

Non-Negativity of Slack Variables:

\[\xi_i \geq 0\]This ensures that the slack variables \(\xi_i\) are always non-negative, as they represent the degree of violation of the margin. Since it’s not possible to have a negative violation, this constraint enforces that \(\xi_i\) cannot be less than zero.

Wrapping Up

The maximum-margin classifier forms the foundation of modern support vector machines. For non-linearly separable data, the introduction of slack variables allows SVMs to adapt while maintaining their core principle of maximizing the margin.

In the next post, we’ll dive deeper into the world of SVMs, explore how they work under the hood, and work through this optimization problem to solve it. Stay tuned!