Multiclass Classification - Overview

Motivation

So far, most of the classification algorithms we have encountered focus on binary classification, where the goal is to distinguish between two classes. For instance, sentiment analysis classifies text as either positive or negative, while spam filters differentiate between spam and non-spam emails.

However, real-world problems often involve more than two categories, making binary classification insufficient. Document classification may require labeling articles into over ten categories, object recognition must identify objects among thousands of classes, and face recognition must distinguish between millions of individuals.

As the number of classes grows, several challenges arise. Computation cost increases significantly, especially when training separate models for each class. Additionally, some classes might have far fewer examples than others, leading to class imbalance issues. Finally, in some cases, different types of errors have varying consequences—for example, misidentifying a handwritten “3” as an “8” might be less problematic than confusing a stop sign with a yield sign in an autonomous driving system.

Given these challenges, we need effective strategies to extend binary classification techniques to handle multiple classes efficiently.

Reducing Multiclass to Binary Classification

A natural way to approach multiclass classification is by reducing it to multiple binary classification problems. One naive approach is to represent each class using a unique binary code and train a classifier to predict the code (000, 001, 010). Another approach is to apply regression, where each class is assigned a numerical value (1.0, 2.0, 3.0), and the model predicts a continuous number that is rounded to the nearest class. However, these methods often fail in practice due to poor generalization.

Instead, two well-established techniques are commonly used:

- One-vs-All (OvA), also called One-vs-Rest

- All-vs-All (AvA), also known as One-vs-One

These methods decompose the problem into smaller binary classification tasks while ensuring that the final model can still distinguish between all classes.

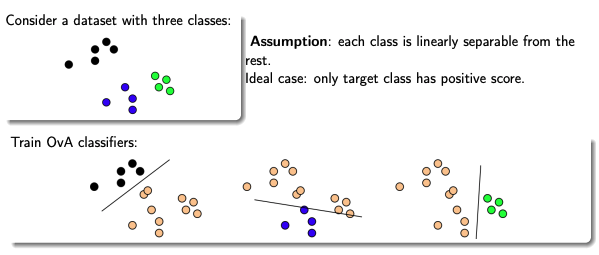

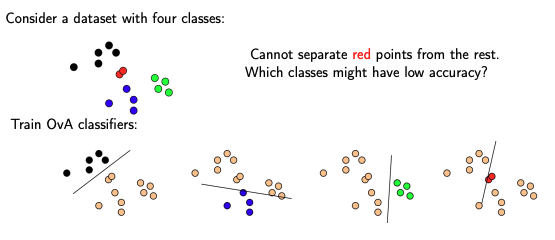

One-vs-All (OvA)

The One-vs-All (OvA) approach works by training one binary classifier per class. Each classifier is responsible for distinguishing a single class from all the others.

Training

Given a dataset with \(k\) classes, we train \(k\) separate classifiers:

- Each classifier \(h_i\) learns to recognize class \(i\) as positive (+1) while treating all other classes as negative (-1).

- Formally, each classifier is a function \(h_i: X \to \mathbb{R}\), where a higher score indicates a higher likelihood of belonging to class \(i\).

Prediction

When a new input \(x\) is given, we evaluate all \(k\) classifiers and select the class with the highest score:

\[h(x) = \arg\max_{i \in \{1, \dots, k\}} h_i(x)\]If multiple classifiers output the same score, we can resolve ties arbitrarily.

Example: 3-Class Problem

Consider a classification task with three categories: cats, dogs, and rabbits. Using OvA, we train three classifiers:

- A classifier that distinguishes cats from dogs and rabbits.

- A classifier that distinguishes dogs from cats and rabbits.

- A classifier that distinguishes rabbits from cats and dogs.

At test time, each classifier produces a score, and the class with the highest score is selected.

However, this method has some limitations. If the data is not linearly separable, the decision boundaries can become ambiguous. Additionally, if one class has far fewer examples than others, the classifier for that class might be undertrained, leading to class imbalance issues.

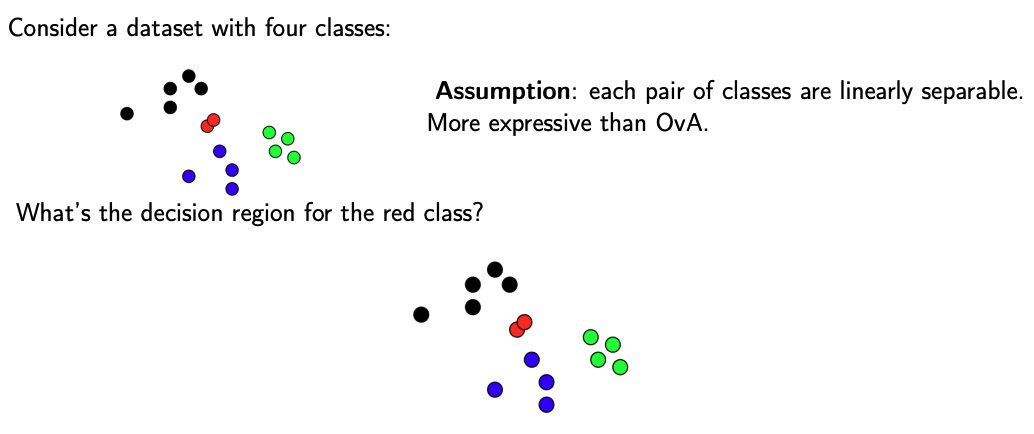

All-vs-All (AvA)

A more refined approach is All-vs-All (AvA), also known as One-vs-One. Instead of training one classifier per class, we train a separate classifier for each pair of classes.

Training

For a dataset with \(k\) classes, we train \(\frac{k(k-1)}{2}\) binary classifiers:

- Each classifier \(h_{ij}\) is trained to distinguish class \(i\) from class \(j\).

- Formally, each classifier \(h_{ij}: X \to \mathbb{R}\) outputs a score, where a positive value indicates class \(i\), and a negative value indicates class \(j\).

Prediction

At test time, each classifier makes a decision between its assigned two classes. Each class receives a vote based on the number of times it wins in pairwise comparisons. The final prediction is the class with the most votes:

\[h(x) = \arg\max_{i \in \{1, \dots, k\}} \sum_{j \ne i} [ \underbrace{h_{ij}(x)\mathbb{I}\{i < j\}}_{\text{class } i \text{ is } +1} - \underbrace{h_{ji}(x)\mathbb{I}\{j < i\}}_{\text{class } i \text{ is } -1} ]\]Again, in scenarios where multiple classes receive the same number of votes, a tournament-style approach can be used to break ties. Here, classes compete in a series of pairwise matchups, and the winner of each round advances until only one class remains—the final prediction.

Example: 4-Class Problem

Suppose we have four classes. Using AvA, we train six classifiers:

- A classifier for cats vs. dogs

- A classifier for cats vs. rabbits

- A classifier for cats vs. birds

- A classifier for dogs vs. rabbits

- A classifier for dogs vs. birds

- A classifier for rabbits vs. birds

At test time, each classifier votes for a class, and the class with the most votes is chosen as the final prediction.

This method has better decision boundaries than OvA because it learns finer distinctions between pairs of classes. However, it is computationally expensive for large \(k\), as the number of classifiers grows quadratically.

OvA vs. AvA: Trade-offs

Both approaches have their own advantages and limitations. In general:

- OvA is simpler and requires fewer models, but it suffers from class imbalance issues.

- AvA provides better decision boundaries but is computationally expensive, especially for large numbers of classes.

The following table summarizes the computational complexity of both methods:

| OvA | AvA | |

|---|---|---|

| Training Complexity | \(O(k B_{\text{train}}(n))\) | \(O(k^2 B_{\text{train}}(n/k))\) |

| Testing Complexity | \(O(k B_{\text{test}})\) | \(O(k^2 B_{\text{test}})\) |

| Challenges | Class imbalance, poor calibration | Small training sets, tie-breaking |

-

\(k\): The number of classes in the multiclass classification problem.

-

\(B_{\text{train}}(n)\): The computational cost of training a binary classifier on \(n\) training examples.

-

\(B_{\text{test}}\): The computational cost of testing a single input using one binary classifier.

- For One-vs-All (OvA):

- Training:

- Train \(k\) classifiers, each on the entire dataset with \(n\) examples.

- Total training cost: \(O(k \cdot B_{\text{train}}(n))\)

- Testing:

- For each new input, all \(k\) classifiers are evaluated.

- Total testing cost per input: \(O(k \cdot B_{\text{test}})\)

- Training:

- For All-vs-All (AvA):

- Training:

- Train \(\frac{k(k-1)}{2} \approx O(k^2)\) classifiers.

- Each classifier uses data from only two classes, approximately \(n/k\) examples.

- Total training cost: \(O(k^2 \cdot B_{\text{train}}(n/k))\)

- Testing:

- For each new input, all \(O(k^2)\) classifiers are evaluated.

- Total testing cost per input: \(O(k^2 \cdot B_{\text{test}})\)

- Training:

While these reduction-based approaches work well for small numbers of classes, they become impractical when scaling to large datasets.

Conclusion

We explored two fundamental approaches for handling multiclass classification by reducing it to multiple binary classification problems:

- One-vs-All (OvA): Train one classifier per class.

- All-vs-All (AvA): Train one classifier per pair of classes.

Although these methods are simple and effective for small datasets, they become computationally expensive as the number of classes grows. For example, ImageNet contains over 20,000 categories, and Wikipedia has over 1 million topics, making reduction-based methods infeasible.

What’s Next?

To overcome these challenges, we need classification algorithms that directly generalize binary classification to multiple classes without breaking the problem into smaller binary tasks. In the next post, we’ll explore these approaches and how they scale efficiently to large datasets. Stay tuned and See you! 👋