Multiclass Classification with SVM

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) are widely used for binary classification, but how do we extend them to multiclass problems? This post dives into the generalization of SVMs to multiclass settings, focusing on deriving the loss function intuitively and mathematically.

Note: We’ve already covered SVMs in detail across multiple blog posts, so if any part of the SVM-related content here feels unclear, I highly recommend revisiting those earlier discussions. You can find the full list of all related blogs here.

From Binary to Multiclass: Revisiting the Margin

For binary classification, the margin for a given training example \((\mathbf{x}^{(n)}, y^{(n)})\) is defined as:

\[y^{(n)} \mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x}^{(n)}\]Here, we want this margin to be large and positive, meaning the classifier confidently assigns the correct label — i.e., the sign of \(\mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x}^{(n)}\) matches \(y^{(n)}\).

In the multiclass setting, instead of a single weight vector \(\mathbf{w}\), we associate each class \(y \in \mathcal{Y}\) with a class-specific score function \(h(\mathbf{x}, y)\). The margin becomes a difference of scores:

\[h(\mathbf{x}^{(n)}, y^{(n)}) - h(\mathbf{x}^{(n)}, y)\]This represents how much more confident the model is in the correct class over an incorrect one. Again, we want this margin to be large and positive for all \(y \neq y^{(n)}\).

Multiclass SVM: The Separable Case

Let’s build intuition by recalling the hard-margin binary SVM:

Binary Objective:

\[\min_{\mathbf{w}} \ \frac{1}{2} \|\mathbf{w}\|^2\]Subject to:

\[y^{(n)} \mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x}^{(n)} \geq 1 \quad \forall (\mathbf{x}^{(n)}, y^{(n)}) \in \mathcal{D}\]Now, for the multiclass case, we again aim for a margin of at least 1, but now between the correct class and every other class:

Define the margin for each incorrect class \(y\) as:

\[m_{n,y}(\mathbf{w}) \overset{\text{def}}{=} \langle \mathbf{w}, \Psi(\mathbf{x}^{(n)}, y^{(n)}) \rangle - \langle \mathbf{w}, \Psi(\mathbf{x}^{(n)}, y) \rangle\]Then, the optimization becomes:

Multiclass Objective:

\[\min_{\mathbf{w}} \ \frac{1}{2} \|\mathbf{w}\|^2\]Subject to:

\[m_{n,y}(\mathbf{w}) \geq 1 \quad \forall (\mathbf{x}^{(n)}, y^{(n)}) \in \mathcal{D}, \quad y \neq y^{(n)}\]This ensures the score of the correct class exceeds the score of every other class by at least 1.

Here’s a way to visualize it:

In contrast to the binary case, where the margin measures alignment between the weight vector and the input (modulated by the true label), the multiclass margin compares the model’s score for the correct label against its score for any incorrect label. This pairwise difference captures how much more the model “prefers” the correct class over a specific incorrect one. Intuitively, it’s no longer about pushing a single decision boundary away from the origin, but about ensuring the score of the true class is separated from all others by a margin — effectively enforcing a set of inequalities that distinguish the correct class from each competitor. This formulation naturally generalizes the binary margin while preserving the core idea: confident, separable predictions.

Think of it like a race where the correct class isn’t just expected to win — it must outpace every other class by a clear stride. It’s not enough to cross the finish line first; it has to do so with a visible lead. The margin enforces this separation, ensuring the model’s predictions are not just accurate, but decisively confident.

From Hard Margins to Hinge Loss

In practice, perfect separation may not be possible, especially in noisy datasets or complex decision boundaries. To handle these scenarios, we shift to a soft-margin approach using hinge loss, which allows for some misclassification while still enforcing the desired separation between classes.

Binary Hinge Loss Recap:

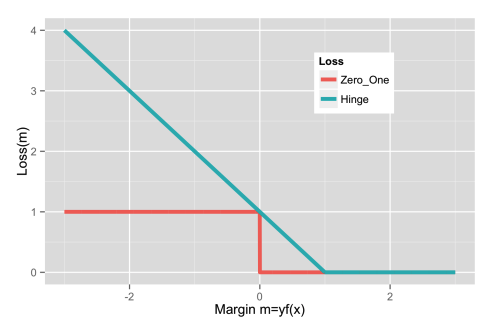

Hinge loss provides a convex upper bound on the 0-1 loss, which is commonly used in classification tasks. The binary hinge loss is defined as:

\[\ell_{\text{hinge}}(y, \hat{y}) = \max(0, 1 - y h(\mathbf{x}))\]Here, \(y\) is the true label, \(h(\mathbf{x})\) is the score or decision function (typically \(h(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x}\) for a linear classifier), and \(\hat{y}\) is the predicted label. This loss function penalizes predictions that are either incorrect (when \(y \neq \hat{y}\)) or too close to the decision boundary (when \(\vert 1 - y h(\mathbf{x}) \vert\) is small).

Generalized Hinge Loss for Multiclass Classification

In the case of multiclass classification, the situation is more complex because we are dealing with more than two possible classes. In this setting, the goal is to ensure that the classifier correctly ranks the true class higher than the others, with a margin that is as large as possible.

Let’s define the multiclass 0-1 loss as:

\[\Delta(y, y') = \mathbb{I}[y \neq y']\]Where \(\mathbb{I}[\cdot]\) is the indicator function, which is 1 if \(y \neq y'\) and 0 if \(y = y'\). More generally, \(\Delta\) can encode different misclassification costs, allowing for a more flexible model.

The model’s predicted class \(\hat{y}\) is the one that maximizes the score function \(h(\mathbf{x}, y)\) across all classes:

\[\hat{y} \overset{\text{def}}{=} \arg\max_{y' \in \mathcal{Y}} \langle \mathbf{w}, \Psi(\mathbf{x}, y') \rangle\]Here, \(\Psi(\mathbf{x}, y')\) represents the feature transformation for class \(y'\) and input \(\mathbf{x}\), and \(\mathcal{Y}\) is the set of all possible classes.

For a correct prediction, we want:

\[\langle \mathbf{w}, \Psi(\mathbf{x}, y) \rangle \geq \langle \mathbf{w}, \Psi(\mathbf{x}, \hat{y}) \rangle\]Where \(y\) is the true class. However, if this condition is violated and the classifier incorrectly chooses an alternative class, we need to quantify the degree of misclassification using the hinge loss.

To upper-bound the 0-1 loss, we use the following inequality:

\[\Delta(y, \hat{y}) \leq \Delta(y, \hat{y}) - \langle \mathbf{w}, \Psi(\mathbf{x}, y) - \Psi(\mathbf{x}, \hat{y}) \rangle\]This may seem a bit abstract at first, but here’s the intuition: if the model predicts \(\hat{y} \neq y\), then the 0-1 loss is 1, and we want to penalize the model based on how poorly it ranked the true class. The inner product difference quantifies how much higher the model scores the incorrect class \(\hat{y}\) over the true class \(y\). By subtracting this difference from the misclassification cost \(\Delta(y, \hat{y})\), we effectively create a margin-based upper bound on the discrete loss.

This turns the hard-to-optimize, non-differentiable 0-1 loss into a continuous, convex surrogate that encourages the correct class to score higher than incorrect ones — making it suitable for optimization using gradient-based methods.

Example to Internalize the Intuition:

Suppose you’re classifying handwritten digits, and the true label is \(y = 3\). The model incorrectly predicts \(\hat{y} = 8\) with the following scores:

- Score for class 3: 7.2

- Score for class 8: 7.8

So the model prefers class 8 over the correct class 3. The inner product difference is:

\[\langle \mathbf{w}, \Psi(\mathbf{x}, 3) - \Psi(\mathbf{x}, 8) \rangle = 7.2 - 7.8 = -0.6\]Assuming a standard 0-1 loss with \(\Delta(3, 8) = 1\), the hinge loss upper bound becomes:

\[1 - (-0.6) = 1.6\]The model is penalized more than 1 because it was confidently wrong.

Now consider a less confident mistake:

- Score for class 3: 7.2

- Score for class 8: 7.1

Then,

\[\langle \mathbf{w}, \Psi(\mathbf{x}, 3) - \Psi(\mathbf{x}, 8) \rangle = 7.2 - 7.1 = 0.1\]and the hinge loss becomes:

\[1 - 0.1 = 0.9\]Still incorrect, but the model is barely wrong, so the penalty is smaller. This example illustrates how the hinge loss upper bound captures how wrong a prediction is — not just whether it’s wrong.

Finally with this, we arrive at the generalized multiclass hinge loss:

\[\ell_{\text{hinge}}(y, \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{w}) \overset{\text{def}}{=} \max_{y' \in \mathcal{Y}} \left[ \Delta(y, y') - \langle \mathbf{w}, \Psi(\mathbf{x}, y) - \Psi(\mathbf{x}, y') \rangle \right]\]This loss function is designed to penalize misclassifications while ensuring that the true class \(y\) is clearly separated from all other classes \(y'\). It is zero if the margin between the true class and all other classes exceeds the corresponding cost, meaning the prediction is both correct and confident. In cases where the true class is not sufficiently separated from an incorrect class, the hinge loss penalizes the model, pushing it to improve the separation.

This approach, by enforcing a margin between classes, ensures that the classifier learns to correctly distinguish between classes in a way that is robust to small errors or noise in the training data. The key difference from the binary case is that we now have to consider pairwise comparisons between the true class and each possible alternative class, making the task of learning the optimal decision boundaries more complex, but also more flexible.

Final Objective: Multiclass SVM with Hinge Loss

To put everything together, we incorporate the generalized multiclass hinge loss into a regularized optimization framework — just like in the binary SVM case. The goal is to not only minimize classification errors but also control the model complexity to avoid overfitting.

We achieve this by combining the hinge loss with an \(L_2\) regularization term. The resulting objective is:

Multiclass SVM Objective:

\[\min_{\mathbf{w} \in \mathbb{R}^d} \ \frac{1}{2} \|\mathbf{w}\|^2 + C \sum_{n=1}^{N} \max_{y' \in \mathcal{Y}} \left[ \Delta(y^{(n)}, y') - \langle \mathbf{w}, \Psi(\mathbf{x}^{(n)}, y^{(n)}) - \Psi(\mathbf{x}^{(n)}, y') \rangle \right]\]Here:

- The first term, \(\frac{1}{2} \|\mathbf{w}\|^2\), is the regularization term. It encourages the model to find a weight vector with small norm, promoting simpler decision boundaries and better generalization.

- The second term accumulates the hinge loss over all training examples, penalizing violations of the desired margins based on the cost function \(\Delta(y^{(n)}, y')\).

Each training example contributes to the loss only if the margin between the correct class \(y^{(n)}\) and some incorrect class \(y'\) is less than the cost \(\Delta(y^{(n)}, y')\). If all margins exceed their respective costs, the hinge loss evaluates to zero for that example — meaning it’s classified correctly and confidently, with no penalty incurred.

This objective function forms the basis of many structured and multiclass prediction models, striking a balance between fitting the training data and maintaining a margin-based decision boundary that generalizes well.

What Comes Next: Optimization

Now that we have a continuous, convex surrogate loss, the next step is to optimize the objective. This typically involves minimizing the regularized hinge loss using gradient-based methods or specialized algorithms like stochastic subgradient descent. The form of the loss allows us to compute subgradients efficiently, even though the max operator introduces non-smoothness. By iteratively updating the weights to reduce the loss, we arrive at a classifier that balances margin maximization with error minimization, and generalizes well to unseen data.

Wrapping Up

Multiclass SVM loss builds on binary SVMs by comparing the score of the correct label with that of every other label, incorporating misclassification costs, and optimizing using hinge loss. The formulation retains interpretability and extends the margin-based principle elegantly into the multiclass realm.

Stay tuned for a follow-up post on implementing multiclass SVMs using structured prediction techniques!