Random Forests

After understanding the power of bagging to reduce variance by combining multiple models, a natural question arises: Can we make this idea even stronger?

Bagging helps, but when the individual models (like decision trees) are still correlated, variance reduction is not as efficient as it could be. This brings us to the motivation for a more advanced ensemble method — Random Forests.

Motivating Random Forests: Handling Correlated Trees

Let’s revisit an important insight we learned from bagging.

Suppose we have independent estimates \(\hat{\theta}_1, \dots, \hat{\theta}_n\) satisfying:

\[\mathbb{E}[\hat{\theta}_i] = \theta, \quad \text{Var}(\hat{\theta}_i) = \sigma^2\]Then:

-

The mean of the estimates is:

\[\mathbb{E}\left[\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \hat{\theta}_i\right] = \theta\] -

And the variance of the mean is:

\[\text{Var}\left(\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \hat{\theta}_i\right) = \frac{\sigma^2}{n}\]

This shows that averaging independent estimators reduces variance effectively.

However, in practice, if the estimators \(\hat{\theta}_i\) are correlated, the variance reduction is less effective. Why is that? Let’s break it down.

What Happens When Estimators are Correlated?

To understand this, consider that each estimator \(\hat{\theta}_i\) has some variance on its own. If these estimators are independent, averaging them reduces the total variance by a factor of \(\frac{1}{n}\) (as we saw earlier in bagging). This is because independence means that the errors or fluctuations in one model don’t affect the others.

But, when estimators are correlated, this doesn’t hold true anymore. In fact, the variance reduction becomes less effective. The reason for this is that correlation introduces covariance terms.

- Covariance is a measure of how much two random variables change together. If two estimators are correlated, the error in one model is likely to be reflected in the other. This reduces the benefit of averaging since both estimators will likely “make similar mistakes.”

A Simple Example

Imagine you’re trying to estimate the weight of an object. Suppose you have two different methods (estimators) to measure this weight:

- Estimator 1 measures the weight but has some error due to a systematic bias (e.g., the scale is always slightly off by 1kg).

- Estimator 2 is another scale that also has a bias, but it happens to be the same as Estimator 1.

Now, if these two estimators have the same bias, they are correlated because they both tend to make the same mistake. Averaging the two estimations won’t help much because both estimators have the same error. So, the resulting variance after averaging will not reduce as much as we would expect with independent estimators.

Why Are Bootstrap Samples Not Fully Independent?

Now, let’s return to bagging, where we train multiple trees on bootstrap samples.

- A bootstrap sample is generated by randomly sampling with replacement from the original dataset. This means that each point in the original dataset has a chance of being included multiple times, and some points may not be included at all.

- These bootstrap samples are independent from each other in terms of how they are created, but they are not independent from the true population distribution \(P_{X \times Y}\).

Why? Because all the bootstrap samples come from the same original dataset, which means they contain the same underlying distribution. If the original dataset has certain features that are particularly strong predictors, these features will often appear at the top of many decision trees across different bootstrap samples. This can make the individual trees more similar to each other than we would like.

For example, consider a dataset where the feature “age” strongly predicts whether a customer will buy a product. If all the bootstrap samples include “age” as a key feature, the decision trees trained on these samples will end up making similar decisions based on “age”. This creates correlation between the predictions of the trees because they are all making similar splits based on the same strong features.

What Does This Mean for Bagging?

In bagging, since the trees are still correlated (due to the shared features across bootstrap samples), the reduction in variance is not as significant as we would expect if the trees were fully independent. This limits the effectiveness of bagging.

Can We Reduce This Correlation?

This is the key challenge addressed by Random Forests. By introducing additional randomness into the process — specifically, by randomly selecting a subset of features at each node when building each tree — we can reduce the correlation between the trees. This leads to a more diverse set of trees, improving the overall performance of the ensemble.

Thus, reducing the correlation between trees is one of the main innovations of Random Forests that makes it more powerful than bagging alone.

To clearly understand how correlation between trees impacts variance reduction, let’s break down the two scenarios with a full mathematical setup.

Setup:

- Suppose we have a dataset \(D = \{x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n\}\), where each \(x_i\) is a feature vector and each corresponding output \(y_i\) is from a true population distribution \(P_{X \times Y}\).

- We are training decision trees, and we want to understand how their predictions are affected by the sampling method.

- We’ll define two key scenarios:

- Independent sampling (ideal case): Each tree in the ensemble is trained on independently drawn samples from the true population \(P_{X \times Y}\).

- Bootstrap sampling: Each tree is trained on a bootstrap sample, which is created by sampling with replacement from the original dataset \(D\).

Case 1: Independent Sampling

Let’s assume that we have two estimators (trees) \(\hat{f}_1(x)\) and \(\hat{f}_2(x)\), both trained independently from the true population. Their predictions are unbiased, and their variances are \(\text{Var}(\hat{f}_1(x)) = \sigma_1^2\) and \(\text{Var}(\hat{f}_2(x)) = \sigma_2^2\). Since they are trained on independent samples, the covariance between their predictions is zero:

\[\text{Cov}(\hat{f}_1(x), \hat{f}_2(x)) = 0\]This means that the two trees are completely independent of each other. When we combine their predictions (by averaging), we can reduce the overall variance of the ensemble:

\[\text{Var}(\hat{f}_{\text{avg}}(x)) = \frac{1}{2} \left( \text{Var}(\hat{f}_1(x)) + \text{Var}(\hat{f}_2(x)) \right) = \frac{\sigma_1^2 + \sigma_2^2}{2}\]Since the predictions are independent, the variance reduces nicely without any issues.

Case 2: Bootstrap Sampling

Now, let’s look at the case of bootstrap sampling. Each decision tree is trained on a bootstrap sample of the original data, which means that the training samples are drawn with replacement from the dataset. This results in correlated trees because:

- Bootstrap samples are independent of each other (each sample is drawn from the dataset), but they are not independent of the true population distribution \(P_{X \times Y}\).

- As a result, the predictions from different trees \(\hat{f}_1(x)\) and \(\hat{f}_2(x)\) are correlated with each other.

Let’s define the correlation coefficient between \(\hat{f}_1(x)\) and \(\hat{f}_2(x)\) as \(\rho\), where \(0 < \rho < 1\). This correlation arises because both trees are trained on slightly different subsets of the data, which means they will make similar predictions on the same inputs.

Now, the variance of the ensemble will depend on both the variance of individual trees and the covariance between them:

\[\text{Var}(\hat{f}_{\text{avg}}(x)) = \frac{1}{2} \left( \text{Var}(\hat{f}_1(x)) + \text{Var}(\hat{f}_2(x)) \right) + \text{Cov}(\hat{f}_1(x), \hat{f}_2(x))\]Since \(\text{Cov}(\hat{f}_1(x), \hat{f}_2(x)) = \rho \cdot \sigma_1 \cdot \sigma_2\), we get:

\[\text{Var}(\hat{f}_{\text{avg}}(x)) = \frac{\sigma_1^2 + \sigma_2^2}{2} + \rho \cdot \sigma_1 \cdot \sigma_2\]Notice that the correlation \(\rho\) causes the variance to not reduce as effectively as in the independent case. The more correlated the trees are, the less variance reduction we achieve, and the ensemble may not perform as well as expected.

Key Differences and Conclusion:

-

Independent Sampling: When the trees are independent, we see maximum variance reduction because there is no covariance between the models. The variance of the average prediction is simply the average of the individual variances.

-

Bootstrap Sampling: When the trees are trained on bootstrap samples, the correlation between the trees reduces the potential for variance reduction. This is because the trees share a common structure due to being trained on similar data. The variance of the average prediction is larger because of the covariance term.

This setup clearly shows how correlation between trees in bootstrap sampling impacts the variance reduction in bagging. The next step to address this issue is through Random Forests, where we introduce further randomness to decorrelate the trees.

Random Forests

Random Forests build upon the foundation of bagging decision trees, but introduce an extra layer of randomness to improve performance and reduce correlation between trees. Here’s how:

- Grow trees independently, just as in bagging, by training each tree on a different bootstrap sample.

- At each split in the tree, instead of considering all available features, randomly select a subset of \(m\) features and split based only on these.

What Does This Change Do?

This adjustment has a significant impact on the performance of the ensemble:

- Reduces correlation between trees: By limiting the set of features considered at each split, trees become less likely to make the same decisions and thus become less correlated with each other.

- Increases diversity among trees: Different features lead to different decision boundaries in each tree, creating a diverse set of models that are not overly similar to each other.

- Improves ensembling effectiveness: With greater diversity, the ensemble as a whole becomes stronger. The averaged predictions from these less correlated trees lead to more robust and accurate results.

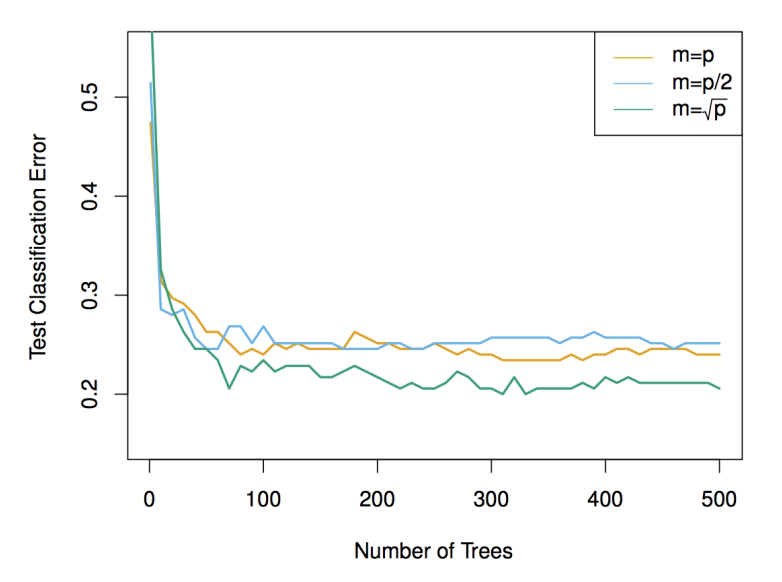

Typical Values for \(m\)

The parameter \(m\) determines the number of features considered at each split. The value of \(m\) is chosen based on the type of task:

-

For classification tasks, it is common to set:

\(m \approx \sqrt{p}\) -

For regression tasks, we typically set:

\(m \approx \frac{p}{3}\)

(where \(p\) is the total number of features.)

These values help strike a balance between randomness and the amount of information available at each decision node.

Important Note:

If you set \(m = p\) (i.e., if each tree is allowed to use all the features at each split), then Random Forests will behave just like bagging — i.e., there will be no additional randomness, and the trees will be fully correlated.

By introducing this random selection of features, Random Forests overcome one of the limitations of bagging (the correlation between trees) and unlock the full power of ensemble learning. This makes Random Forests one of the most powerful and widely used machine learning techniques today.

Review: Recap of Key Concepts

In summary, here’s a quick review of the key points we’ve covered:

-

Deep decision trees generally have low bias (they can fit the training data very well) but high variance (small changes in the data can lead to significant changes in the tree structure).

-

Ensembling multiple models helps reduce variance. The rationale behind this is that the mean of i.i.d. estimates tends to have smaller variance than a single estimate.

-

Bootstrap sampling allows us to simulate many different datasets from a single training set, which is the foundation of bagging.

However, while bagging uses bootstrap samples to train individual models, these models (the decision trees) are correlated, which limits the reduction in variance.

- Random Forests address this by increasing the diversity of the ensemble. They achieve this by selecting a random subset of features at each split of the decision trees, reducing correlation and enhancing performance.

Conclusion

To wrap it up, Random Forests combine the strengths of bagging (reduced variance) with the added benefit of increased diversity among trees. By introducing randomness in feature selection, they make each tree in the ensemble more independent, leading to a stronger, more robust model.

Random Forests stand out as one of the most powerful and widely used techniques in machine learning, thanks to their ability to handle complex data patterns while mitigating overfitting through ensembling and randomness.

Next, we’ll explore Boosting - another powerful ensemble technique that builds models sequentially to improve accuracy by focusing on the mistakes made by previous models.