Regularization - Balancing Model Complexity and Overfitting

When building machine learning models, one of the core challenges is finding the right balance between approximation error and estimation error. The trade-off can be understood in terms of the size and complexity of the hypothesis space, denoted by \(F\).

On the one hand, a larger hypothesis space allows the model to better approximate the true underlying function. However, this flexibility comes at a cost: the risk of overfitting the training data, especially if the dataset is small. On the other hand, a smaller hypothesis space is less prone to overfitting, but it may lack the expressiveness needed to capture the true relationship between inputs and outputs, leading to higher approximation error.

To control this trade-off, we need a way to quantify and limit the complexity of \(F\). This can be done in various ways, such as limiting the number of variables or restricting the degree of polynomials in a model.

How to Control Model Complexity

A common strategy to manage complexity involves learning a sequence of models with increasing levels of sophistication. Mathematically, this sequence can be represented as:

\[F_1 \subset F_2 \subset \dots \subset F_n \subset F\]where each subsequent space, \(F_i\), is a superset of the previous one, representing models of greater complexity.

For example, consider polynomial regression. The full hypothesis space, \(F\), includes all polynomial functions, while \(F_d\) is restricted to polynomials of degree \(\leq d\). By increasing \(d\), we explore more complex models within the same overarching hypothesis space.

Once this sequence of models is defined, we evaluate them using a scoring metric, such as validation error, to identify the one that best balances complexity and accuracy. This approach ensures a systematic way to control overfitting while retaining sufficient expressive power.

Feature Selection in Linear Regression

In linear regression, the concept of nested hypothesis spaces is closely tied to feature selection. The idea is to construct a series of models using progressively fewer features:

\[F_1 \subset F_2 \subset \dots \subset F_n \subset F\]where \(F\) represents models that use all available features, and \(F_d\) contains models using fewer than \(d\) features.

For example, if we have two features, \(\{X_1, X_2\}\), we can train models using the subsets \(\{\}\), \(\{X_1\}\), \(\{X_2\}\), and \(\{X_1, X_2\}\). Each subset corresponds to a different hypothesis space, and the goal is to select the one that performs best according to a validation score.

However, this approach quickly becomes computationally infeasible as the number of features grows. Exhaustively searching through all subsets of features leads to a combinatorial explosion, making it impractical for datasets with many features.

Greedy Feature Selection Methods

To overcome the inefficiency of exhaustive search, greedy algorithms such as forward selection and backward selection are commonly used.

Forward Selection

Forward selection begins with an empty set of features and incrementally adds the most promising feature at each step. Initially, the model contains no features, represented as \(S = \{\}\). At each iteration:

-

For every feature not in the current set \(S\), a model is trained using the combined set \(S \cup \{i\}\).

-

The performance of the model is evaluated, and a score, \(\alpha_i\), is assigned to each feature.

-

The feature \(j\) with the highest score is added to the set, provided it improves the model’s performance.

-

This process repeats until adding more features no longer improves the score.

Backward Selection

Backward selection starts at the opposite end of the spectrum. Instead of beginning with an empty set, it starts with all available features, \(S = \{X_1, X_2, \dots, X_p\}\). At each step, the feature that contributes the least to the model’s performance is removed. This process continues until no further removals improve the model’s score.

Reflections on Feature Selection

Feature selection provides a natural way to control the complexity of a linear prediction function by limiting the number of features. The overarching goal is to strike a balance between minimizing training error and controlling model complexity, often through a scoring metric that incorporates both factors.

While forward and backward selection methods are intuitive and computationally efficient, they have their limitations. For one, they do not guarantee finding the optimal subset of features. Additionally, the subsets selected by the two methods may differ, as the process is sensitive to the order in which features are evaluated.

This brings us to an important question:

Can feature selection be framed as a consistent optimization problem, leading to more robust and reliable solutions?

In the next section, we explore how regularization offers a principled way to tackle this problem, providing a unified framework to balance model complexity and performance.

\(L_1\) and \(L_2\) Regularization

In the previous section, we discussed feature selection as a means to control model complexity. While effective, these methods are often computationally expensive and can lack consistency. Regularization offers a more systematic approach by introducing a complexity penalty directly into the objective function. This allows us to balance prediction performance with model simplicity in a principled manner.

Complexity Penalty: Balancing Simplicity and Accuracy

The idea behind regularization is to augment the loss function with a penalty term that discourages overly complex models. For example, a scoring function for feature selection can be expressed as:

\[\text{score}(S) = \text{training_loss}(S) + \lambda |S|\]where \(|S|\) is the number of selected features, and \(\lambda\) is a hyperparameter that controls the trade-off between training loss and complexity.

A larger \(\lambda\) imposes a heavier penalty on complexity, meaning that adding an extra feature is only justified if it significantly improves the training loss—by at least \(\lambda\). This approach discourages the inclusion of unnecessary features, effectively shrinking the hypothesis space \(F\).

However, directly using the number of features as a complexity measure is non-differentiable, making it hard to optimize. This limitation motivates the use of alternative measures, such as norms on the model weights, which provide a differentiable and computationally efficient framework.

Consider it like this:: Think of choosing ingredients for a dish. The training loss is like the flavor of the dish, and the penalty term is like the cost of adding ingredients. If you add too many ingredients (features), the cost goes up, and the dish may become overcomplicated or unbalanced. By introducing a penalty (regularization), you’re essentially saying, “Only add more ingredients if they significantly improve the flavor.” The larger the penalty (larger \(\lambda\)), the more careful you have to be about adding new ingredients, encouraging simplicity and preventing the dish from becoming too cluttered. This approach keeps the recipe (model) balanced and prevents unnecessary complexity.

Soft Selection Through Weight Shrinkage

Instead of hard feature selection, regularization encourages soft selection by penalizing the magnitude of the model weights. Consider a linear regression model:

\[f(x) = w^\top x\]where \(w_i\) represents the weight for the \(i\)-th feature. If \(w_i\) is zero or close to zero, it effectively excludes the corresponding feature from the model.

Why Shrink Weights?

Intuitively, smaller weights make the model more stable. A regression line with a smaller slope produces smaller changes in the output for a given change in the input. This stability has two key benefits:

-

Reduced Sensitivity to Noise: Smaller weights make the model less prone to overfitting, as predictions are less sensitive to fluctuations in the training data.

-

Better Generalization: By pushing weights toward zero, the model becomes less sensitive to variations in new datasets, improving its robustness.

Weight Shrinkage in Polynomial Regression

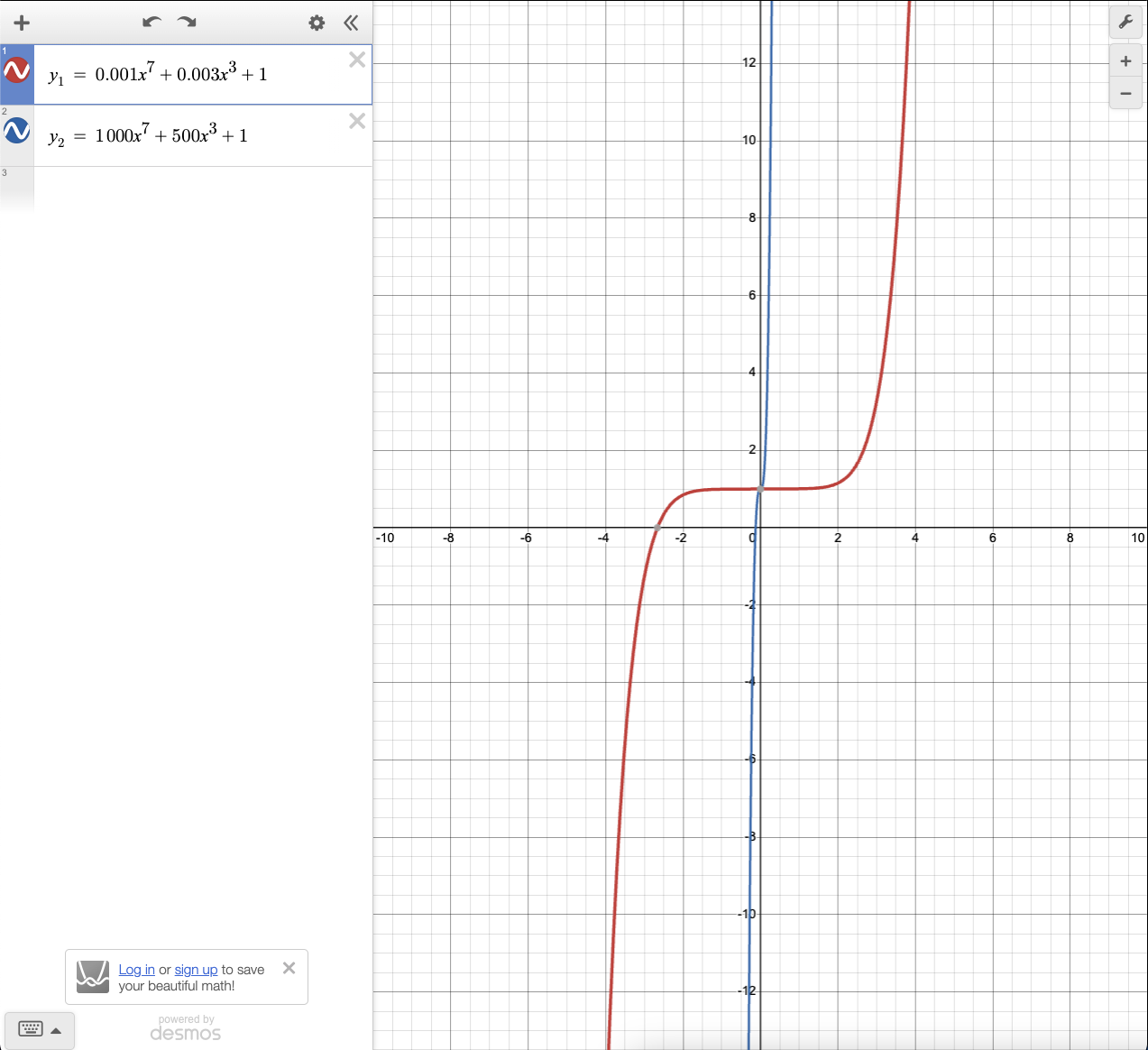

In polynomial regression, where the \(n\)-th feature corresponds to the \(n\)-th power of \(x\), weight shrinkage plays a crucial role in preventing overfitting. For instance, consider two polynomial models:

\[\hat{y} = 0.001x^7 + 0.003x^3 + 1, \quad \text{and} \quad \hat{y} = 1000x^7 + 500x^3 + 1\]The second model has large coefficients, making the curve “wiggle” excessively to fit the training data, a hallmark of overfitting. In contrast, the first model—with smaller weights—is smoother and less prone to overfitting.

Think of it this way: Imagine you’re driving a car down a winding road. A car with a sensitive steering wheel (large weights) will make sharp turns with every slight variation in the road, making the ride bumpy and unpredictable. In contrast, a car with a more stable, less sensitive steering wheel (smaller weights) will handle the same road with smoother, more controlled movements, reducing the impact of small bumps and ensuring a more stable journey. Similarly, in regression, smaller weights lead to smoother, more stable models that are less prone to overfitting and better at handling new data.

Linear Regression with \(L_2\) Regularization

Let’s formalize this idea using linear regression. For a dataset \(D_n = \{(x_1, y_1), \dots, (x_n, y_n)\}\), the objective in ordinary least squares is to minimize the mean squared error:

\[\hat{w} = \arg\min_{w \in \mathbb{R}^d} \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \left( w^\top x_i - y_i \right)^2.\]While effective, this approach can overfit when the number of features \(d\) is large compared to the number of samples \(n\). For example, in natural language processing, it’s common to have millions of features but only thousands of documents.

To address this, \(L_2\) regularization (also known as ridge regression) adds a penalty on the \(L_2\) norm of the weights:

\[\hat{w} = \arg\min_{w \in \mathbb{R}^d} \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \left( w^\top x_i - y_i \right)^2 + \lambda \|w\|_2^2,\]where:

\[\|w\|_2^2 = w_1^2 + w_2^2 + \dots + w_d^2\]This additional term penalizes large weights, shrinking them toward zero. When \(\lambda = 0\), the solution reduces to ordinary least squares. As \(\lambda\) increases, the penalty grows, favoring simpler models with smaller weights.

Intuition: Think of fitting a suit to someone. In ordinary least squares, you would tailor the suit to fit perfectly according to every measurement. However, if the person has an unusual body shape or you have limited data, the suit might end up being too tight in some areas, causing discomfort. With \(L_2\) regularization, it’s like adding some flexibility to the design, allowing for slight adjustments to ensure the suit is comfortable and fits well, even if the measurements aren’t perfect. This prevents overfitting and makes the model more robust, much like a well-tailored suit that remains comfortable under different conditions.

Generalization to Other Models

Although we’ve illustrated \(L_2\) regularization with linear regression, the concept extends naturally to other models, including neural networks. By penalizing the magnitude of weights, \(L_2\) regularization helps improve generalization across a wide range of machine learning tasks.

Closing Thoughts

Regularization, whether through weight shrinkage or complexity penalties, provides a robust mechanism to balance model expressiveness and generalization. In the next section, we’ll explore \(L_1\) regularization, its sparsity-inducing properties, and how it differs from \(L_2\) regularization.