Subgradient and Subgradient Descent

Optimization is a cornerstone of machine learning, as it allows us to fine-tune models and minimize error. For smooth, differentiable functions, gradient descent is the go-to method. However, in the real world, many functions are not differentiable. This is where subgradients come into play. In this post, we’ll explore subgradients, understand their properties, and see how they are used in subgradient descent. Finally, we’ll dive into their application in support vector machines (SVMs).

First-Order Condition for Convex, Differentiable Functions

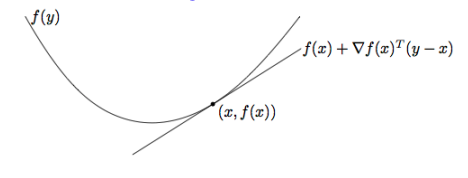

Let’s start with the basics of convex functions. For a function \(f : \mathbb{R}^d \to \mathbb{R}\) that is convex and differentiable, the first-order condition states that:

\[f(y) \geq f(x) + \nabla f(x)^\top (y - x), \quad \forall x, y \in \mathbb{R}^d\]

This equation tells us something profound: the linear approximation to \(f\) at \(x\) is a global underestimator of the function. In other words, the gradient provides a plane below the function, ensuring the convexity property holds. A direct implication is that if \(\nabla f(x) = 0\), then \(x\) is a global minimizer of \(f\). This serves as the foundation for gradient-based optimization.

Subgradients: A Generalization of Gradients

While gradients work well for differentiable functions, what happens when a function has kinks or sharp corners? This is where subgradients step in. A subgradient is a generalization of the gradient, defined as follows:

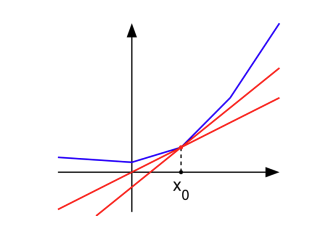

A vector \(g \in \mathbb{R}^d\) is a subgradient of a convex function \(f : \mathbb{R}^d \to \mathbb{R}\) at \(x\) if:

\[f(z) \geq f(x) + g^\top (z - x), \quad \forall z \in \mathbb{R}^d\]

Subgradients essentially maintain the same idea as gradients: they provide a linear function that underestimates \(f\). However, while the gradient is unique, a subgradient can belong to a set of possible vectors called the subdifferential, denoted \(\partial f(x)\).

For convex functions, the subdifferential is always non-empty. If \(f\) is differentiable at \(x\), the subdifferential collapses to a single point: \(\{ \nabla f(x) \}\). Importantly, for a convex function, a point \(x\) is a global minimizer if and only if \(0 \in \partial f(x)\). This property allows us to apply subgradients even when gradients don’t exist.

To build an understanding for subgradients, think of them as a safety net for optimization when the function isn’t smooth. Imagine you’re skiing down a mountain, and instead of a smooth slope, you encounter a flat plateau or a jagged edge. A regular gradient would fail to guide you because there’s no single steepest slope at such points. Subgradients, however, provide a range of valid directions — all the paths you could safely take without “climbing uphill.”

In mathematical terms, subgradients are generalizations of gradients. For a non-differentiable function, the subdifferential \(\partial f(x)\) at a point \(x\) is the set of all possible subgradients. Each of these subgradients \(g\) satisfies:

\[f(z) \geq f(x) + g^\top (z - x), \quad \forall z \in \mathbb{R}^d\]This means that every subgradient defines a hyperplane that lies below the function \(f(x)\). It acts as a valid approximation of the function’s behavior, even at sharp corners or flat regions.

Here’s a useful way to interpret subgradients: if you were to try and “push” the function \(f(x)\) upward using any of the subgradients at \(x\), you would never exceed the true value of \(f(z)\). Subgradients provide all the slopes that respect this property, even when the function isn’t smooth.

Finally, the key insight: if the zero vector is in the subdifferential, \(0 \in \partial f(x)\), it means that there’s no descent direction left — you’ve reached the global minimum. Subgradients help us navigate these tricky, non-smooth terrains where gradients fail, making them a versatile tool in optimization.

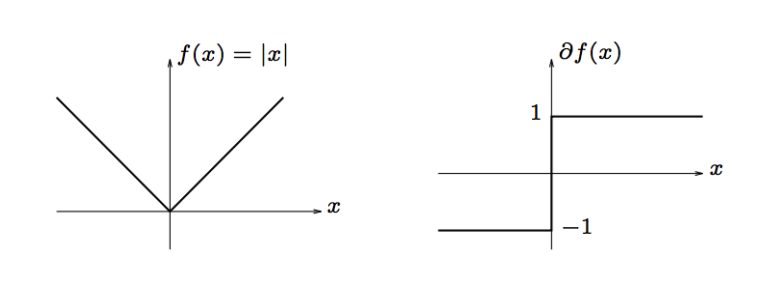

Subgradient Example: Absolute Value Function

Let’s consider a classic example: \(f(x) = \lvert x \rvert\). This function is non-differentiable at \(x = 0\), making it an ideal candidate to illustrate subgradients. The subdifferential of \(f(x)\) is:

\[\partial f(x) = \begin{cases} \{-1\} & \text{if } x < 0, \\ \{1\} & \text{if } x > 0, \\ [-1, 1] & \text{if } x = 0. \end{cases}\]

At \(x = 0\), the subgradient set contains all values in the interval \([-1, 1]\), which corresponds to all possible slopes of lines that underapproximate \(f(x)\) at that point.

Subgradient Descent: The Optimization Method

Subgradient descent extends gradient descent to non-differentiable convex functions. The update rule is simple:

\[x_{t+1} = x_t - \eta_t g,\]where \(g \in \partial f(x_t)\) is a subgradient, and \(\eta_t > 0\) is the step size.

Unlike gradients, subgradients do not always converge to zero as the algorithm progresses. Why? This is because subgradients are not as tightly coupled to the function’s local geometry as gradients are. In gradient descent, the gradient vanishes at critical points (e.g., minima, maxima, or saddle points), forcing the updates to slow down as the algorithm approaches a minimum. However, in subgradient descent, the subgradients remain non-zero even near a minimum due to the nature of subdifferentiability.

For example, consider the absolute value function, \(f(x) = \lvert x \rvert\), which has a sharp corner at \(x = 0\). The subdifferential at \(x = 0\) is the interval \([-1, 1]\), meaning that even at the minimizer \(x^\ast = 0\), valid subgradients exist (e.g., \(g = 0.5\)). Consequently, the algorithm does not inherently “slow down” as it approaches the minimum, unlike gradient descent.

This behavior requires us to carefully choose a decreasing step size \(\eta_t\) to make sure that the updates shrink over time, leading to convergence.

For convex functions, subgradient descent ensures that the iterates move closer to the minimizer:

\[\|x_{t+1} - x^\ast\| < \|x_t - x^\ast\|,\]provided that the step size is small enough. However, subgradient methods tend to be slower than gradient descent because they rely on weaker information about the function’s structure.

Subgradient Descent for SVMs: The Pegasos Algorithm

Subgradients are particularly useful in optimizing the objective function of support vector machines (SVMs). The SVM objective is:

\[J(w) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \max(0, 1 - y_i w^\top x_i) + \frac{\lambda}{2} \|w\|^2,\]where the first term represents the hinge loss, and the second term penalizes large weights to prevent overfitting. Optimizing this objective using gradient-based methods is tricky due to the non-differentiability of the hinge loss. Enter Pegasos, a stochastic subgradient descent algorithm.

The Pegasos Algorithm

The Pegasos algorithm follows these steps:

- Initialize \(w_1 = 0\), \(t = 0\) and \(\lambda > 0\)

- Randomly permute the data at the beginning of each epoch.

- While termination condition not met:

- For each data point \((x_j, y_j)\), update the parameters:

- Increment \(t\): \(t = t + 1\).

- Compute the step size: \(\eta_t = \frac{1}{t \lambda}\).

- If \(y_j w_t^\top x_j < 1\), update: \(w_{t+1} = (1 - \eta_t \lambda) w_t + \eta_t y_j x_j.\)

- Otherwise, update: \(w_{t+1} = (1 - \eta_t \lambda) w_t.\)

- For each data point \((x_j, y_j)\), update the parameters:

This algorithm cleverly combines subgradient updates with a decreasing step size to ensure convergence. The hinge loss ensures that the model maintains a margin of separation, while the regularization term prevents overfitting. By carefully adjusting the step size \(\eta_t = \frac{1}{t \lambda}\), Pegasos ensures convergence to the optimal \(w\) while handling the non-differentiable hinge loss.

Derivation for Both Cases:

-

Case 1: \(y_j w_t^\top x_j < 1\) (misclassified or on the margin)

The subgradient of the hinge loss for this case is:

\[\nabla \text{hinge loss} = -y_j x_j.\]Adding the subgradient of the regularization term:

\[\nabla J(w) = -y_j x_j + \lambda w_t.\]Using the subgradient descent update rule:

\[w_{t+1} = w_t - \eta_t \nabla J(w),\]we get:

\[w_{t+1} = w_t - \eta_t (-y_j x_j + \lambda w_t).\]Simplifying:

\[w_{t+1} = (1 - \eta_t \lambda) w_t + \eta_t y_j x_j.\] -

Case 2: \(y_j w_t^\top x_j \geq 1\) (correctly classified)

In this case, the hinge loss is zero, so the subgradient is purely from the regularization term:

\[\nabla J(w) = \lambda w_t.\]The subgradient descent update rule becomes:

\[w_{t+1} = w_t - \eta_t \nabla J(w).\]Substituting \(\nabla J(w) = \lambda w_t\):

\[w_{t+1} = w_t - \eta_t \lambda w_t.\]Simplifying:

\[w_{t+1} = (1 - \eta_t \lambda) w_t.\]

Wrapping Up

Subgradients are a powerful tool for dealing with non-differentiable convex functions, and subgradient descent provides a straightforward yet effective way to optimize such functions. While slower than gradient descent, subgradient descent shines in scenarios where gradients are unavailable.

In the next part of this series, we’ll delve into the dual problem and uncover its connection to the primal SVM formulation. Stay tuned for more insights into the fascinating world of ML!

References

- Subgradient Methods [To Read]