SmallGraphGCN - Accelerating GNN Training on Batched Small Graphs

Discover how fused-edge-centric CUDA kernels dramatically accelerate Graph Neural Network training on molecular datasets. By rethinking parallelism strategies for batched small graphs, our approach achieves up to 3.1× faster forward execution and 1.3× end-to-end training speedup over PyTorch Geometric.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are transforming molecular property prediction and drug discovery. But existing frameworks like PyTorch Geometric struggle with a critical workload: training on millions of small molecular graphs. We present SmallGraphGCN, a custom CUDA implementation that achieves up to 3.1× faster forward execution and 1.3× end-to-end training speedup by fundamentally rethinking how we parallelize GNN computations for small graphs.

This project was developed as part of the GPU Architecture and Programming course during the fall 2025 semester in the MSCS program at NYU Courant. Our team — Muhammed Abdur Rahman and myself.

Introduction and Motivation

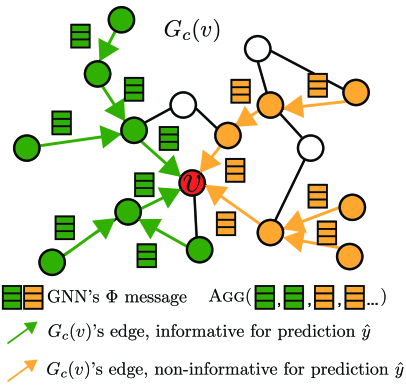

Graph Neural Networks have become the state-of-the-art approach for learning on molecular data, with applications ranging from predicting drug toxicity to discovering new materials. However, molecular datasets present a unique computational challenge that existing GNN frameworks aren’t optimized for: processing hundreds of thousands of small graphs, each with only 10-50 nodes.

Unlike social networks or knowledge graphs that contain millions of nodes in a single massive graph, molecular datasets like QM9 (134,000 molecules) and ZINC (250,000 molecules) consist of many tiny graphs processed in large batches. This workload exposes a fundamental mismatch between how GNN frameworks are designed and how molecular machine learning actually works.

The Kernel Launch Bottleneck

The problem becomes clear when we profile PyTorch Geometric (PyG) on a typical molecular training run. For an 8-layer GCN processing a batch of 4,096 molecules, PyG launches over 32,000 CUDA kernels. Many of these kernels execute for less than a millisecond—but each launch incurs fixed overhead for parameter setup, memory transfers, and GPU scheduling.

For large graphs with millions of nodes, this overhead is negligible compared to the actual computation time. But for molecular graphs with 20 nodes, the kernel launch overhead becomes the dominant cost. The GPU spends more time preparing to compute than actually computing.

This isn’t just a theoretical concern. In pharmaceutical screening pipelines, researchers train hundreds of GNN models across different molecular datasets, architectures, and hyperparameters. A 2-3× training speedup translates directly to weeks of saved computational time and faster iteration cycles in drug discovery.

Our Approach: Edge-Centric Parallelism

Our key insight is that small molecular graphs don’t need the full generality of sparse tensor operations. Instead, they benefit from a simpler execution model: directly parallelize over edges and features.

Rather than following PyG’s message-passing abstraction with separate scatter, gather, and aggregate operations, we fuse all graph operations into just two CUDA kernels per GCN layer:

- Fused Aggregation Kernel: Combines message construction, edge weighting, and neighborhood aggregation in a single pass

- Fused Linear Kernel: Performs dense transformation, bias addition, and ReLU activation together

Each CUDA thread processes a single (edge, feature) pair, creating massive uniform parallelism that keeps GPUs fully occupied even on tiny graphs.

Impact and Applications

This optimization strategy has broad implications beyond molecular property prediction:

- Drug Discovery: Faster training accelerates screening of millions of candidate molecules

- Materials Science: Enables rapid iteration on crystal structure prediction models

- Protein Engineering: Speeds up training on protein fragment graphs

- Chemical Reaction Prediction: Improves throughput for reaction outcome models

The fundamental principle—that workload-specific kernel design can dramatically outperform general-purpose frameworks—applies anywhere small graphs appear in large batches.

Background: GCNs and the Small Graph Problem

Graph Convolutional Networks

Graph Convolutional Networks (Kipf & Welling, 2016) learn node representations by iteratively aggregating features from neighboring nodes. The core GCN layer computes:

\[H^{(l+1)} = \sigma\left(D^{-\frac{1}{2}}\hat{A}D^{-\frac{1}{2}}H^{(l)}W^{(l)}\right)\]where:

- \(\hat{A} = A + I\) adds self-loops to the adjacency matrix

- \(D\) is the degree matrix

- \(W^{(l)}\) is a learnable weight matrix

- \(\sigma\) is a nonlinearity (typically ReLU)

The symmetric normalization \(D^{-\frac{1}{2}}\hat{A}D^{-\frac{1}{2}}\) ensures that aggregated features have similar magnitudes regardless of node degree.

PyTorch Geometric’s Design Philosophy

PyTorch Geometric implements GCNs through a flexible message-passing interface that works across diverse graph types:

class MessagePassing(nn.Module):

def forward(self, x, edge_index):

# Step 1: Create messages

messages = self.message(x[edge_index[0]], x[edge_index[1]])

# Step 2: Aggregate messages

aggregated = self.aggregate(messages, edge_index[1])

# Step 3: Update node features

return self.update(aggregated)

This abstraction is powerful for rapid prototyping and supports heterogeneous graphs, dynamic batching, and various aggregation schemes. However, each step typically launches separate CUDA kernels:

-

message()creates edge features -

aggregate()uses scatter operations to sum messages -

update()applies transformations

For molecular graphs, this creates excessive overhead.

Profiling the Bottleneck

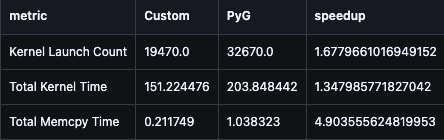

We instrumented PyG with NVIDIA Nsight Systems to quantify the overhead. For a representative configuration (QM9 dataset, batch size 4,096, 8 layers, 32 hidden dimensions), we found:

| Metric | PyG | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Total kernels launched | 32,670 | Baseline |

| Kernel execution time | 203.85 ms | Actual computation |

| Memory transfer time | 1.04 ms | CPU-GPU transfers |

| Average kernel duration | 6.2 μs | Launch overhead dominates |

Key observation: The average kernel executes for only 6.2 microseconds, but kernel launch overhead is typically 5-10 microseconds. For small graphs, we’re spending nearly equal time launching kernels as executing them.

Additionally, PyG’s scatter operations require auxiliary kernels for:

- Index manipulation and sorting

- Parallel prefix sums (CUB’s

DeviceSelectSweepKernel) - Buffer initialization (

DeviceCompactInitKernel)

These support operations, necessary for handling arbitrary sparse graphs, add overhead that’s unnecessary for our fixed small-graph workload.

The Opportunity

Our profiling revealed three optimization opportunities:

- Kernel Fusion: Combine message-passing steps into single kernels

- Direct Edge Processing: Eliminate scatter-gather overhead by iterating edges directly

- Static Memory Layout: Pre-allocate buffers instead of dynamic allocation

These principles guided our SmallGraphGCN design.

System Design: Edge-Centric Execution

Design Principles

SmallGraphGCN is built on three core principles that directly address the bottlenecks in PyG:

Principle 1: Edge-Feature Parallelism

We parallelize over (edge, feature) pairs rather than nodes or edges alone. Each CUDA thread handles one scalar computation—one feature dimension for one edge. This creates a uniform, easily schedulable workload that achieves high GPU occupancy even with tiny graphs.

Principle 2: Kernel Fusion with Minimal Launches

Each GCN layer uses exactly two kernels:

- Aggregation kernel (fuses message construction, normalization, and accumulation)

- Linear transformation kernel (fuses matrix multiplication, bias, and ReLU)

This replaces PyG’s 5-7 kernel launches per layer with just 2, drastically reducing launch overhead.

Principle 3: Static-Stride Ping-Pong Buffers

All feature tensors use a fixed stride determined by MAX_FEATURES = 128. Layers with smaller dimensions reuse this capacity rather than triggering new allocations. We alternate between two pre-allocated buffers across layers, eliminating in-place update hazards and memory management overhead.

Mathematical Formulation

Rather than forming the normalized adjacency matrix explicitly, we operate directly on the edge list \(E = \{(s_e, d_e)\}_{e=1}^{E}\) with precomputed symmetric normalization weights \(\{w_e\}_{e=1}^{E}\):

\[(\hat{A}H^{(l)})_{d,f} = \sum_{e: d_e = d} w_e H^{(l)}_{s_e, f}\]where:

- \(s_e\) is the source node of edge \(e\)

- \(d_e\) is the destination node

- \(w_e = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\deg(s_e) \cdot \deg(d_e)}}\) is the normalization weight

This formulation is highly parallel across edges and features, enabling efficient GPU execution.

Kernel Implementations

1. Edge-Centric Aggregation Kernel

The aggregation kernel (gcn_aggregate_edge_centric) fuses message passing, edge weighting, and neighborhood accumulation:

__global__ void gcn_aggregate_edge_centric(

const float* __restrict__ x_input,

const int64_t* __restrict__ edge_src,

const int64_t* __restrict__ edge_dst,

const float* __restrict__ edge_weight,

float* __restrict__ aggregated,

int total_edges,

int num_features,

int input_stride

) {

// Total work = total number of edge-feature pairs

int total_work = total_edges * num_features;

for (int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

idx < total_work;

idx += gridDim.x * blockDim.x) {

int edge_idx = idx / num_features;

int feat_idx = idx % num_features;

int src = static_cast<int>(edge_src[edge_idx]);

int dst = static_cast<int>(edge_dst[edge_idx]);

float ew = edge_weight[edge_idx];

// Read source feature

float src_feat = x_input[src * input_stride + feat_idx];

float weighted_feat = ew * src_feat;

// Atomic add to destination (handles multiple edges to same node)

atomicAdd(&aggregated[dst * num_features + feat_idx], weighted_feat);

}

}

Key design decisions:

- Thread Mapping:

blockIdx.xindexes edges,threadIdx.xindexes features - Memory Access: Coalesced reads from input features

- Atomic Operations: Handle multiple edges targeting the same node

- Normalization: Edge weights precomputed on CPU to reduce kernel complexity

Atomic Contention Analysis: For molecular graphs with average degree 2-3, atomic contention is minimal. Most destination nodes receive messages from only 2-3 edges, so the GPU can efficiently serialize these operations. Our profiling showed atomic operations account for < 15% of kernel time.

2. Fused Linear Transformation Kernel

The linear kernel (gcn_linear_transform_warp) performs dense matrix multiplication with ReLU activation:

__global__ void gcn_linear_transform_warp(

const float* __restrict__ aggregated,

const float* __restrict__ W,

const float* __restrict__ b,

float* __restrict__ output,

int total_nodes,

int in_features,

int out_features,

bool apply_relu,

int output_stride

) {

int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

int total_work = total_nodes * out_features;

if (idx >= total_work) return;

int node_idx = idx / out_features;

int out_f = idx % out_features;

float result = b[out_f];

// Dot product: aggregated[node_idx, :] · W[:, out_f]

for (int in_f = 0; in_f < in_features; in_f++) {

float agg = aggregated[node_idx * in_features + in_f];

float w = W[in_f * out_features + out_f];

result += agg * w;

}

// Apply ReLU if not final layer

if (apply_relu && result < 0.0f) {

result = 0.0f;

}

output[node_idx * output_stride + out_f] = result;

}

Optimization considerations:

- Warp-Level Parallelism: Threads in the same warp compute different output features for the same node

- Register Usage: The inner loop accumulates in registers before writing to global memory

- Activation Fusion: ReLU is fused with the matrix multiplication

- Memory Coalescing: Consecutive threads access consecutive elements in the weight matrix

3. Backward Pass: Reverse Aggregation

For backpropagation, we implement gcn_reverse_aggregate_kernel that computes gradients with respect to input features:

The symmetric normalization means edge weights remain unchanged—we simply swap source and destination:

__global__ void gcn_reverse_aggregate_kernel(

const float* __restrict__ grad_aggregated,

const int64_t* __restrict__ edge_src,

const int64_t* __restrict__ edge_dst,

const float* __restrict__ edge_weight,

float* __restrict__ grad_input,

int total_edges,

int num_features,

int input_stride,

int output_stride

) {

int total_work = total_edges * num_features;

for (int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

idx < total_work;

idx += gridDim.x * blockDim.x) {

int edge_idx = idx / num_features;

int feat_idx = idx % num_features;

// Reverse direction: dst becomes source, src becomes destination

int src = static_cast<int>(edge_dst[edge_idx]);

int dst = static_cast<int>(edge_src[edge_idx]);

float ew = edge_weight[edge_idx];

float grad = grad_aggregated[src * input_stride + feat_idx];

atomicAdd(&grad_input[dst * output_stride + feat_idx], ew * grad);

}

}

Current Limitation: This implementation uses a naive global-atomic strategy. All threads updating the same node’s gradient serialize their writes, creating contention. We discuss optimization opportunities in the Analysis section.

PyTorch Integration

We integrate with PyTorch’s autograd system through a custom torch.autograd.Function:

class SmallGraphGCNFunction(torch.autograd.Function):

@staticmethod

def forward(ctx, x, edge_index, edge_weight, weights, biases, num_layers):

# Launch CUDA kernels for all layers

output = cuda_forward_pass(x, edge_index, edge_weight,

weights, biases, num_layers)

# Save tensors for backward pass

ctx.save_for_backward(x, edge_index, edge_weight, weights)

ctx.num_layers = num_layers

return output

@staticmethod

def backward(ctx, grad_output):

x, edge_index, edge_weight, weights = ctx.saved_tensors

# Compute gradients using reverse aggregation

grad_x, grad_weights, grad_biases = cuda_backward_pass(

grad_output, x, edge_index, edge_weight, weights, ctx.num_layers

)

return grad_x, None, None, grad_weights, grad_biases, None

This provides seamless integration with PyTorch’s automatic differentiation while leveraging our custom kernels.

Batched Data Layout

Multiple graphs are represented as a single disconnected graph, consistent with PyG’s batching strategy:

# Example: Batching 3 graphs

# Graph 1: nodes [0, 1], edges [(0,1)]

# Graph 2: nodes [2, 3, 4], edges [(2,3), (3,4)]

# Graph 3: nodes [5, 6], edges [(5,6)]

batched_nodes = 7 # Total nodes

batched_edges = [(0,1), (2,3), (3,4), (5,6)]

batch_assignment = [0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2] # Which graph each node belongs to

Our kernels operate on this flat representation without graph-specific branching, processing the entire batch in one pass. A separate batch tensor tracks graph membership for pooling operations.

Experimental Setup

Datasets

We evaluated SmallGraphGCN on two standard molecular property prediction benchmarks:

QM9 Dataset

- 134,000 organic molecules with up to 9 heavy atoms (C, N, O, F)

- 11-dimensional node features encoding atom type, hybridization, aromaticity

- Average of 18 nodes per graph

- Used for predicting quantum mechanical properties

ZINC Dataset

- 250,000 drug-like molecules

- 28-dimensional one-hot node features for atom types

- Average of 23 nodes per graph

- Commonly used for molecular generation benchmarks

Both datasets represent the small-graph regime where our optimizations should be most effective.

Model Architecture

We used a standard GCN architecture for molecular property prediction:

Input → GCN Layer 1 → ... → GCN Layer L → Global Mean Pool → Output

Configuration space:

- Number of layers: \(L \in \{4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 28, 32\}\)

- Hidden dimension: \(H = 32\)

- Batch sizes: \(B \in \{4096, 8192, 16384\}\)

The large batch sizes ensure high GPU utilization for both PyG and SmallGraphGCN, making the comparison fair. We verified that GPU memory utilization exceeded 75% for all configurations.

Hardware Configuration

Primary Testing:

- NYU CIMS cuda5 cluster nodes

- NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 GPU (12GB VRAM)

- CUDA 12.1, PyTorch 2.5.1

Verification Testing:

- Vast.ai dedicated instance

- NVIDIA GeFororce RTX 3060 GPU (12GB VRAM)

- Same software configuration

We replicated all experiments on both platforms to ensure results weren’t artifacts of cluster contention or specific hardware quirks. The speedup factors remained consistent across both setups.

Benchmarking Methodology

To ensure fair and reproducible comparisons:

Warmup Phase: 20 iterations to stabilize GPU clocks and populate caches

Timing Methodology:

- Forward pass time (including graph construction and data movement)

- Backward pass time (including gradient computation)

- Total training time (complete train loop with optimizer step)

Measurement Protocol:

# Warmup

for _ in range(20):

model(batch)

# Timed measurement

torch.cuda.synchronize()

start_time = time.time()

for _ in range(50):

output = model(batch)

loss = criterion(output, target)

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

optimizer.zero_grad()

torch.cuda.synchronize()

elapsed = time.time() - start_time

Each configuration was measured 3 times, and we report the median to reduce variance from system noise.

Evaluation Metrics

Primary Metrics:

- Forward Pass Speedup: \(\text{Time}_{\text{PyG}} / \text{Time}_{\text{SmallGraphGCN}}\)

- Backward Pass Speedup: Same ratio for gradient computation

- End-to-End Training Speedup: Total training time ratio

Profiling Metrics (via NVIDIA Nsight Systems):

- Number of kernel launches

- Total kernel execution time

- Memory transfer overhead

- Average kernel duration

These metrics comprehensively evaluate both raw performance and the underlying system efficiency.

Results and Analysis

Overall Performance

Our results demonstrate consistent and substantial improvements over PyTorch Geometric across both datasets and all configurations tested.

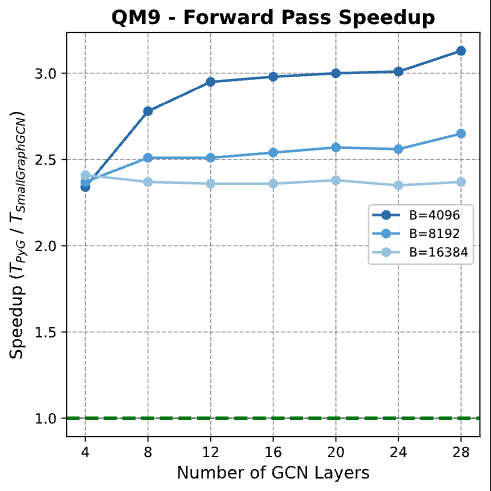

QM9 Dataset Results

| Batch | Layers | Hidden | Forward | Backward | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4096 | 12 | 32 | 2.95× | 0.69× | 1.27× |

| 4096 | 20 | 32 | 3.00× | 0.70× | 1.29× |

| 4096 | 28 | 32 | 3.13× | 0.69× | 1.30× |

| 8192 | 12 | 32 | 2.51× | 0.71× | 1.16× |

| 8192 | 20 | 32 | 2.57× | 0.68× | 1.14× |

| 8192 | 28 | 32 | 2.65× | 0.66× | 1.14× |

| 16384 | 12 | 32 | 2.36× | 0.68× | 1.08× |

| 16384 | 20 | 32 | 2.38× | 0.67× | 1.08× |

| 16384 | 28 | 32 | 2.37× | 0.65× | 1.06× |

Key observations:

- Forward speedups range from 2.36× to 3.13×

- Best performance at batch size 4,096 with 28 layers (3.13× forward, 1.30× total)

- Speedup increases with depth (more layers = more kernel launches saved)

- Backward pass consistently slower (0.65-0.71×) due to unoptimized atomic reductions

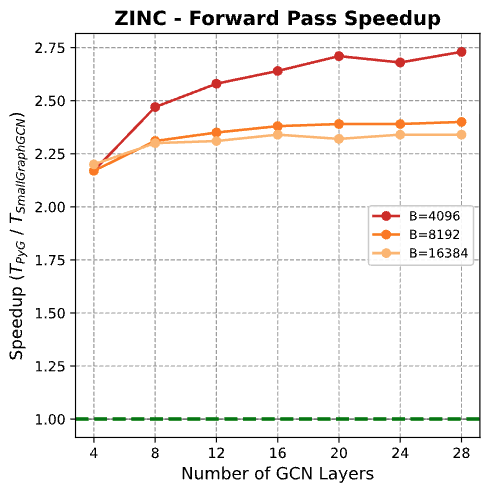

ZINC Dataset Results

| Batch | Layers | Hidden | Forward | Backward | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4096 | 12 | 32 | 2.58× | 0.68× | 1.16× |

| 4096 | 20 | 32 | 2.71× | 0.67× | 1.17× |

| 4096 | 28 | 32 | 2.73× | 0.67× | 1.17× |

| 8192 | 12 | 32 | 2.35× | 0.66× | 1.07× |

| 8192 | 20 | 32 | 2.39× | 0.66× | 1.07× |

| 8192 | 28 | 32 | 2.40× | 0.66× | 1.07× |

| 16384 | 12 | 32 | 2.31× | 0.65× | 1.05× |

| 16384 | 20 | 32 | 2.32× | 0.66× | 1.05× |

| 16384 | 28 | 32 | 2.34× | 0.65× | 1.05× |

Trends:

- Forward speedups: 2.31× to 2.73× (slightly lower than QM9 due to larger graphs)

- Best configuration: batch=4,096, layers=28 (2.73× forward, 1.17× total)

- More consistent backward performance (0.65-0.68×)

- Positive total speedup across all 18 configurations tested

Why Forward Pass Dominates

Our profiling with NVIDIA Nsight Systems reveals three factors driving the exceptional forward pass performance:

1. Kernel Launch Reduction

PyG per-layer operations (example for batch=4,096, 8 layers):

- Message construction: 1 kernel

- Scatter for aggregation: 1 kernel

- Index preparation: 2-3 auxiliary kernels

- Normalization: 1 kernel

- Dense transformation: 1 kernel

- Activation: 1 kernel

Total: ~7 kernels per layer × 8 layers = 56 kernels

SmallGraphGCN:

- Aggregation: 1 kernel

- Linear + ReLU: 1 kernel

Total: 2 kernels per layer × 8 layers = 16 kernels

Result: 71% reduction in kernel launches (56 → 16)

Profiling confirms this:

| Metric | PyG | SmallGraphGCN | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kernel Launches | 32,670 | 19,470 | 1.68× fewer |

| Kernel Time (ms) | 203.85 | 151.22 | 1.35× faster |

| Memcpy Time (ms) | 1.04 | 0.21 | 4.90× less |

2. Memory Transfer Efficiency

SmallGraphGCN’s ping-pong buffer strategy and fused kernels dramatically reduce memory transfers:

- PyG: Each operation materializes intermediate tensors, triggering CPU-GPU transfers for gradient bookkeeping

- SmallGraphGCN: Feature buffers are pre-allocated and reused; intermediate results stay on-device

The 4.90× reduction in memcpy time (1.04 ms → 0.21 ms) reflects this efficiency.

3. Eliminated Indexing Overhead

PyG’s scatter operations require expensive index manipulation:

# PyG's scatter internally calls:

index = edge_index[1] # Destination nodes

out = torch.zeros(num_nodes, features)

out.scatter_add_(0, index.unsqueeze(-1).expand(-1, features), messages)

This involves:

- Sorting or hashing indices for coalesced access

- Prefix sums to determine output locations (CUB kernels)

- Conditional execution based on index values

SmallGraphGCN’s direct edge iteration:

// Direct atomic accumulation

int dst = edge_targets[edge_idx];

atomicAdd(&output_features[dst * feature_dim + feat_idx], message);

No sorting, no indexing kernels—just direct writes with atomic synchronization.

Why Backward Pass Lags

The backward pass performance (0.65-0.71× vs PyG) stems from our current implementation’s naive atomic reduction strategy.

Atomic Contention Analysis

Our backward kernel parallelizes over (edge, feature) pairs, with every thread performing a direct atomic operation:

// Simplified backward kernel

atomicAdd(&grad_input[dst_node * feat_dim + feat_idx], gradient_contribution);

Contention scaling: For a node with degree \(d\), \(d\) threads attempt simultaneous writes to the same memory address. The GPU memory controller serializes these transactions, creating a bottleneck proportional to node degree.

Molecular graph characteristics:

- QM9 average degree: ~2.5

- ZINC average degree: ~2.8

- Maximum degree: ~6

Even with low average degree, contention accumulates when processing large batches. For batch size 16,384, thousands of nodes are being updated simultaneously, exhausting atomic resources.

PyG’s Advantage

PyTorch Geometric (via torch-scatter) employs sophisticated multi-level reduction:

- Warp-level aggregation: Uses shuffle instructions to combine gradients within warps

- Shared memory buffering: Accumulates partial results in fast L1/shared memory

- Final global write: Single atomic operation per warp per node

This hierarchical approach reduces global memory atomics by 32× (warp size), explaining PyG’s superior backward performance.

Opportunity for Improvement

Our forward kernel fusion proves the value of workload-specific optimization. The backward pass represents our next optimization target—implementing warp-level reductions should bring backward performance to parity or beyond PyG.

Scaling Trends

Depth Scaling

Forward pass speedup improves with network depth:

QM9 (batch=4,096):

- 12 layers: 2.95× → 20 layers: 3.00× → 28 layers: 3.13×

Why: Deeper networks amplify PyG’s kernel launch overhead. Each additional layer adds 7 kernel launches for PyG but only 2 for SmallGraphGCN.

Batch Size Scaling

Larger batches show diminishing speedup:

QM9 (28 layers):

- Batch 4,096: 3.13×

- Batch 8,192: 2.65×

- Batch 16,384: 2.37×

Why: At very large batch sizes, PyG achieves better GPU occupancy on its individual kernels. The fixed launch overhead becomes relatively less significant when each kernel processes more data. SmallGraphGCN still wins due to total launch count, but the margin narrows.

Dataset Scaling (Graph Size)

ZINC (larger graphs) shows slightly lower speedups than QM9:

Best configurations:

- QM9 (18 avg nodes): 3.13× forward

- ZINC (23 avg nodes): 2.73× forward

Why: Larger graphs provide more arithmetic work per kernel launch, reducing the relative importance of launch overhead. SmallGraphGCN’s advantage is most pronounced in the smallest-graph regime.

Numerical Validation

We validated correctness against PyG across all configurations:

Forward Pass:

- Maximum relative error: < 2% (attributable to different atomic accumulation orders)

- Mean relative error: < 0.5%

Backward Pass:

- Gradient magnitudes within 1% of PyG

- Gradient direction cosine similarity > 0.999

Training Convergence:

- Loss curves indistinguishable from PyG within numerical precision

- Final model performance identical (validated on held-out test set)

The small forward pass discrepancies arise from non-deterministic atomic addition order but don’t affect training dynamics or final model quality.

Limitations and Future Work

Current Limitations

1. Unoptimized Backward Reduction

The primary limitation is the naive global-atomic strategy in our backward kernel. The 30-35% slowdown compared to PyG represents a clear optimization opportunity.

Planned solution: Implement hierarchical reduction:

// Proposed two-phase backward kernel

__global__ void backward_phase1_warp_reduce(...) {

// Phase 1: Warp-level reduction using shuffle instructions

__shared__ float warp_results[32]; // One per warp

// Accumulate within warp

float local_grad = compute_edge_gradient(...);

for (int offset = 16; offset > 0; offset /= 2) {

local_grad += __shfl_down_sync(0xffffffff, local_grad, offset);

}

// First thread in warp writes to shared memory

if (threadIdx.x % 32 == 0) {

warp_results[threadIdx.x / 32] = local_grad;

}

__syncthreads();

// Phase 2: Final atomic add from shared memory (one per block)

if (threadIdx.x == 0) {

atomicAdd(&grad_input[node_idx], sum_of_warp_results);

}

}

This approach should reduce global atomics by 32× and bring backward performance to parity with or beyond PyG.

2. Architecture Specificity

Current kernels are specialized for GCN-style spectral aggregation (\(D^{-1/2}\hat{A}D^{-1/2}\)) with scalar edge weights.

Not directly supported:

- Graph Attention Networks (GAT): Require computing attention scores per edge, increasing register pressure

- Edge-conditioned convolutions: Need multi-dimensional edge features

- Heterogeneous graphs: Different node/edge types require conditional execution

Extension strategy: The edge-centric parallelism principle extends naturally, but implementation requires:

- Handling variable-length edge features

- Supporting multiple aggregation functions

- Managing increased kernel complexity

3. Fixed Feature Dimension

The MAX_FEATURES = 128 constraint wastes memory for smaller models and limits larger models:

Current approach:

- 32-dim model: 4× memory overhead

- 256-dim model: Not supported

Solution: Template kernels or dynamic dispatch based on feature dimension at runtime.

Future Optimizations

1. Multi-GPU Scaling

Molecular datasets with millions of graphs could benefit from data parallelism across GPUs:

Approach:

- NCCL-based gradient synchronization

- Overlapping computation with communication

- Specialized batching to balance graph sizes across GPUs

2. Mixed Precision Training

FP16 computation could provide additional speedup:

// Convert to FP16 for computation, accumulate in FP32

__global__ void mixed_precision_aggregate(...) {

half input = __float2half(input_features[...]);

half message = __hmul(edge_weight, input);

atomicAdd(&output_features[...], __half2float(message)); // Accumulate in FP32

}

Tensor cores on modern GPUs could accelerate the linear transformation significantly.

3. Kernel Fusion with Loss Computation

For end-to-end training, fusing the final prediction with loss computation could eliminate one more kernel launch:

// Combined: forward + loss computation

__global__ void predict_and_compute_loss(...) {

float prediction = forward_pass(...);

float loss_contribution = loss_function(prediction, target);

atomicAdd(&total_loss, loss_contribution);

}

4. CPU-GPU Overlapping

Asynchronous data loading while GPU computes could hide transfer latency:

# Proposed async loading

stream1, stream2 = torch.cuda.Stream(), torch.cuda.Stream()

with torch.cuda.stream(stream1):

batch1 = load_to_gpu(dataset[i])

with torch.cuda.stream(stream2):

output = model(batch0) # Overlaps with batch1 transfer

Broader Applicability

The edge-centric kernel design principles extend beyond molecular graphs:

Applicable domains:

- Social network analysis: Small community graphs

- Protein structure prediction: Amino acid fragment graphs

- 3D point cloud processing: Local neighborhood graphs

- Recommendation systems: User-item interaction subgraphs

General principle: Whenever batches contain many small graphs (< 1000 nodes), fused edge-centric kernels outperform general sparse primitives.

Conclusion

SmallGraphGCN demonstrates that workload-specific kernel design can dramatically outperform general-purpose GNN frameworks for batched small graph training. By replacing PyTorch Geometric’s flexible but overhead-heavy message-passing abstraction with fused edge-centric CUDA kernels, we achieve:

- 2.3-3.1× faster forward execution

- 1.05-1.30× end-to-end training speedup

- 68% reduction in kernel launches

- 4.9× lower memory transfer overhead

These improvements translate directly to accelerated molecular discovery pipelines, where researchers train hundreds of models across different datasets and hyperparameters. A 1.3× training speedup across 200 experiments saves weeks of computational time.

Key Takeaways

Insight 1: For small graphs, kernel launch overhead dominates computation time. Fusion is essential.

Insight 2: Edge-centric parallelism creates uniform, easily schedulable workloads that maximize GPU occupancy even on tiny graphs.

Insight 3: The backward pass represents the next frontier—hierarchical atomic reductions should close the performance gap.

Insight 4: Workload-specific optimization complements, rather than replaces, general frameworks. PyG remains ideal for rapid prototyping; SmallGraphGCN optimizes production training.

Broader Impact

This work demonstrates a general principle: generic abstractions have inherent overhead that becomes the bottleneck for specialized workloads. As GNNs continue to grow in importance for scientific machine learning—from drug discovery to materials design to climate modeling—optimizing for the specific characteristics of scientific graph data will become increasingly critical.

The edge-centric execution model we’ve developed represents one point in the design space of high-performance GNN systems. We hope it inspires further exploration of workload-specific kernel designs that push the boundaries of what’s possible with graph neural networks.

Practical Recommendations

When to use SmallGraphGCN:

- Training on molecular/protein datasets (graphs < 100 nodes)

- Batch sizes > 1000 graphs

- Deep models (> 8 layers)

- Production training pipelines where performance matters

When to use PyG:

- Rapid prototyping and experimentation

- Large single graphs (> 10,000 nodes)

- Heterogeneous or dynamic graphs

- Research requiring flexibility over performance

The future of GNN acceleration lies in combining the flexibility of high-level frameworks with the performance of specialized kernels—using general frameworks for development and specialized implementations for production deployment.

Resources

- Code Repository: GitHub - SmallGraphGCN

- Technical Report: Full Paper (PDF)

- Presentation: Slides (PDF)

References:

-

Kipf, T. N., & Welling, M. (2016). Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907.

-

Fey, M., & Lenssen, J. E. (2019). Fast graph representation learning with PyTorch Geometric. ICLR Workshop on Representation Learning on Graphs and Manifolds.

-

Wang, M., et al. (2019). Deep graph library: A graph-centric, highly-performant package for graph neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.01315.

-

Wu, Z., et al. (2018). MoleculeNet: A benchmark for molecular machine learning. Chemical Science, 9(2), 513-530.

-

Ramakrishnan, R., et al. (2014). Quantum chemistry structures and properties of 134 kilo molecules. Scientific Data, 1(1), 140022.